Derek Chauvin had 16 complaints made against him that were closed with 'no discipline.' A former member of the police review board says that's proof of a broken system.

by Haven Orecchio-Egresitz- Derek Chauvin, the Minneapolis police officer who is charged in the murder of George Floyd, had 18 complaints made against him since 2001.

- Complaints against police are supposed to end up in front of the city’s conduct review board.

- A former member, though, told Insider the panel meets infrequently, doesn’t meet with the complainant, and panelists aren’t told whether their recommendation ends up making a difference.

- Visit Insider’s homepage for more stories.

During the 20 years that preceded Minneapolis Officer Derek Chauvin’s killing of George Floyd, 18 complaints of misconduct had already been filed against him.

Two of the complaints resulted in a “letter of reprimand,” but the 16 others had no repercussions at all – and none of their contents have been released to the public.

The apparent lack of accountability and transparency in the handling of prior issues with Chauvin has raised a question: What is even the point of the city’s’ Police Conduct Review board?

Kenneth Rance, a North Minneapolis resident who served on the city’s police conduct review board from 2016 until December, said that as it stands now, he’s not sure it’s effective at all.

Cities around the country have formed versions of the boards, which are intended to act as an outside oversight agency for incidents that arise within the police department.

In Minneapolis the board is made up of half officers and half citizens representing each of the city’s wards.

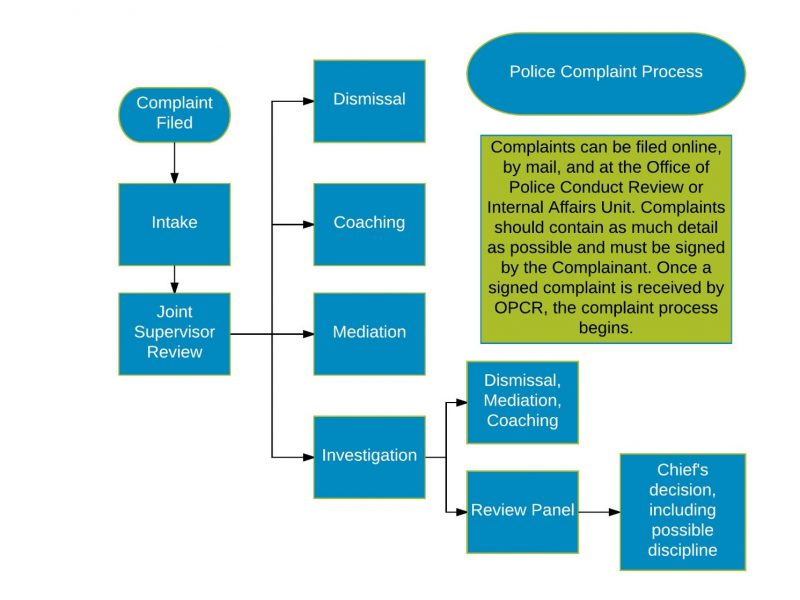

When a complaint is made against an officer in the department, it is first reviewed internally, according to Rance.

If the complaining party is unhappy with the discipline, or lack thereof, he or she can appeal it to the review board, which is overseen by the city’s Department of Civil Rights, he said.

But Rance said in the three years he served on the board, he was only called to review a case six or seven times, and several of them were internal officer-on-officer complaints.

During each case, Rance was given a stack of materials, including the complaint, the police testimony and any available documentation of the incident. He never got the opportunity to meet with the complaining party in person.

After reviewing the case, Rance said he would make a recommendation to the police chief, who ultimately has the authority to discipline.

Not once, though, did Rance find out whether his reccomendation had been accepted.

“The lack of communication within that department is not very good, in the least,” he said. “I have met the Civil Rights Director of a maximum of once, and that was at a community event. How is that possible?” Rance told Insider. “I would have liked to continue [on the panel], but there is so much dysfunction, and a lack of communication.”

Police review committees are necessary, but often structured in a way that prohibits them from being effective

Gbenga Ajilore, senior economist at the Center for American Progress and expert on criminal justice, said the experience that Rance described can be the problem with these community oversight boards.

The panels, he said, were birthed out of the Rodney King trial, when citizens were first confronted by the lack of repercussions for misbehaving police officers.

In 1991, King was violently beaten by LAPD officers during his arrest. The police responsible were acquitted of their crimes.

Following the King case, there was a “big push legislatively” to fix the system, Ajilore said, and one of the results was the formation of citizen police review committees that are called in to look at complaints made against officers.

“The problem is that its very difficult to actually get some sort of board that’s going to have the teeth to make a difference,” Ajilore explained.

Many of these boards, Ajilore said, tend to be made up of police, or retired police, who essentially perform “rubber stamping” when problematic reports arise.

“Then, on the other end of the spectrum, you have these fully independent, fully resourced board that actually can make reccomendation that the city council and mayor can act upon,” Ajilore said. “But again, there really hasn’t been any sort of evidence, that show that they’re effective either.”

That’s because “there is a lot of pushback,” he said. “And that goes to the issue of police unions and what they’re able to do and how they’re able to combat any sort of independent oversight.”

Lorenzo M. Boyd, the director of The Center of Advanced Policing at the Henry C. Lee College of Criminal Justice and Forensic Sciences, noted the same issues with the oversight groups.

The sociologist worked in the Boston Sheriff’s Department for 15 years before transitioning to a career as an academic.

He described himself as a fan of citizen review boards, but realizes that, in a lot of cases, they fall short of achieving their goal.

“If you’re just making recommendations to the chief, the chief can say no,” he said. “If there is a lot of inaction, I’m OK with the police review board going to the media.”

In Minneapolis, though, there’s no way to know if there is action, Rance said. Whenever he made a recommendation on a case, he said, he was never informed of the outcome.

“I kind of liken it to working on an assembly line and making widgets. Once it goes around the corner, you don’t know what happens,” Rance said. “It was never really clearly communicated to me.”

Boyd still sees the potential benefits of the boards, but noted the need for them to carry more weight. “I absolutely see them as valuable,” he said. “I think city governments need to give them a lot more autonomy and a little more strength.”

When officers continue to get away with misconduct, there is nothing stopping their problematic behavior from escalating

Ajilore pointed to the history of complaints stacked up against Chauvin as an example of the lack of accountability in policing.

“That officer knew he was being videotaped, still killed the guy, and knew there was nothing that would happen,” he said. “Think about it, if you go to a store and try to steal something and someone has a camera on you, you’re going to stop right? You’re afraid you’re going to get caught. But if you don’t think you’re going to get caught, who cares if you’re recorded? Who cares if someone’s looking?”

“Then think about what would have to happen for you to have that mentality of being comfortable stealing from the store,” he added.

While Rance said he never reviewed a complaint made against Chauvin himself, he noted that many of the officers whose issues ended up in front of him had a history of other accusations – some of them significant – made against them.

“When it comes to reform, it’s an institutional issue,” Ajilore said. “People keep saying, well that guy was a bad apple. But if it’s a bad apple, and you don’t take it out of the barrel, then the whole thing will rot.”

Rance – who is black – strongly believes that a majority of the police officers in Minneapolis are hardworking and responsible. The problem that he sees is that there is a history of complacency around the small percentage of officers with a violent history.

“I liken it to if you were diagnosed with cancer and you didn’t treat it,” he said.

Rance said that the threat of falling victim to an overly aggressive police officer makes it difficult to live a healthy life in the city. He fears for the safety of his 11-year-old son, 14-year-old daughter, and wife.

He’s even afraid for himself when he’s out exercising in the city.

“Minneapolis has the top-rated park system in the country. I live four blocks from the Mississippi River. I ride along the river, and it is beautiful, but I’m not at peace,” he said. “People are killing us.”

The city police department’s motto, Rance said, is “to protect with courage, to serve with compassion.”

“It’s ironic,” he said. “From what we saw from that video, it was ‘to attack with cowardliness, to harm with inhumanity.’ That’s the model of MPD when it comes to black men.”

- Read more:

- ‘I can’t breathe’: 4 Minneapolis police officers were fired following their involvement in a black man’s death after a cop knelt on his neck for 8 minutes

- New video appears to show police forcing George Floyd out of his car moments before an officer knelt on his neck for 8 minutes

- Photos show thousands of protesters demanding justice in Minneapolis after police killed George Floyd

- Most Minnesota law enforcement agencies ban the neck-pinning maneuver used against George Floyd – but it’s still allowed in Minneapolis