Massey's Alison Brook looks at how we are responding to a world-scale natural disaster that is killing jobs super-fast and what the resulting long-term unemployment will will do to economic prospects

by Alison BrookThe economic effect of the coronavirus is an unprecedented event, described by ex-Fed chairman Ben Bernake as more like a natural disaster than a recession, and because of this, it has required unprecedented fiscal responses. As the world moved into lockdown, one of the ways many economies around the world have tried to protect their economies is through wage protection schemes.

The frantic attempts to keep workers connected with their place of employment in many parts of the world is mind-boggling in its scale:

- Under New Zealand’s wage subsidy the Government had paid out $10.6 billion of the wage subsidy to 1.72 million people by 1 May (more than half of the total employed workforce).

- Australia’s JobKeeper subsidy is expected to provide AU$70 billion in support and at the end of April covering 3.3 million employees.

- In the UK they have an employee furlough scheme where the government pays workers 80 percent of their salary to stay at home and not work. It is currently paying out to around 7.5 million employees, a quarter of Britain’s private sector workforce. The scheme is being extended to October 2020 although from August workers can return to their jobs on a part-time basis.

- Similar schemes are in place in Germany, France and Ireland providing support for many millions more workers (10 million in Germany, 12 million in France and 450,000 in Ireland).

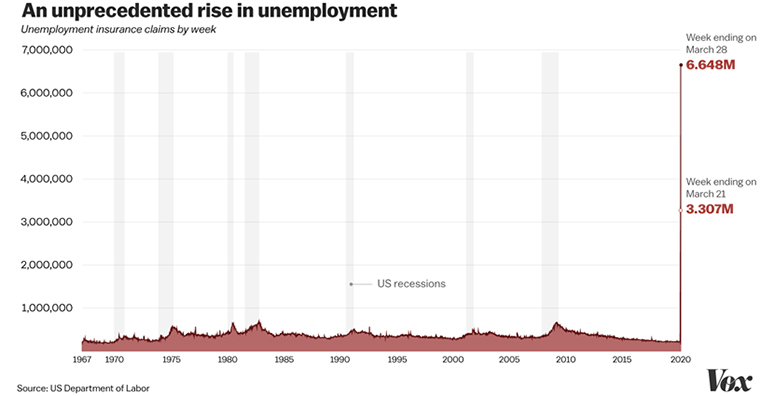

By contrast, in the US where workers are primarily directed onto unemployment benefits rather than retaining their connection with their employment, the immediate effects on jobless claims have been stark:

Recent research from Pew Research shows one-third of Americans live in households where someone has lost a job or taken a pay cut (or both) due to the coronavirus outbreak.

Wage subsidies are not a new thing and have been studied since the 1930s although their effectiveness has been shown to be limited. Time will tell if the current efforts are effective in retaining jobs once the wage subsidy schemes come to an end or whether it just delays the inevitable job losses to follow. In New Zealand’s case, this effect will become evident after the first tranche of the subsidy ends on 9th June to be replaced by a modified subsidy until September. Many are predicting, despite the government’s optimism, that redundancies will soar.

The relationship between recessions and unemployment

According to StatsNZ, the employment impacts of the last major recession in New Zealand (the Global Financial Crisis) were:

- people worked fewer hours

- the number of available jobs fell

- unemployment rose

- more people moved into study

- there were fewer, and smaller, wage rises

- labour market turnover slowed

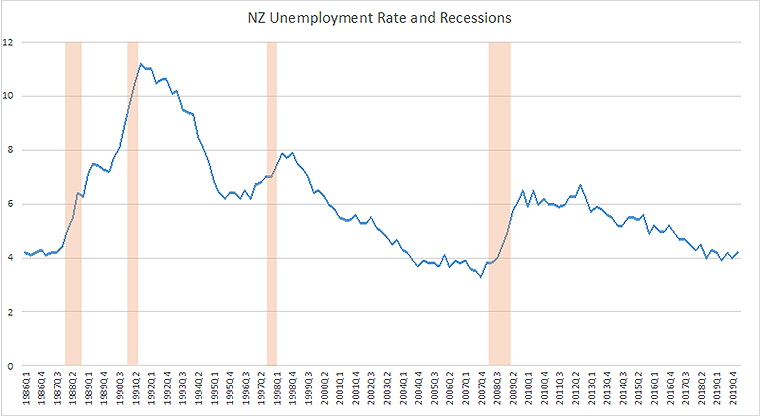

The link between recessions and unemployment is well documented. Unemployment continues to rise after the recession is technically over. And unemployment rates take a long time, often many years, to recover to pre-recessionary levels:

Sources: Stats NZ and RBNZ based on NZ’s Classical Real GDP Business Cycles

Treasury forecasts estimate unemployment reaching a peak 9.8 percent by September this year, but dropping to just 5.7 percent by 2022 but this looks increasingly optimistic with many businesses in the retail and tourism sector unable to trade at anywhere near previous levels. Those on the jobseeker benefit alone jumped from 145,000 before the lockdown to over 184,000 at the start of May, higher than the peak of the GFC at 174,630.

It is hard to see how the economy will absorb all of the jobs lost due to whole industries essentially disappearing or reshaping overnight. According to MBIE’s latest Jobs Online Report (Jobs Online measures changes in online job advertisements from four internet job boards: SEEK, Trade Me Jobs, the Education Gazette and Kiwi Health Jobs. Online job advertisements are a proxy for all job advertisements.) “Online advertisements fell by 6.4 percent during the March 2020 quarter, and by 12.5 percent between March 2019 and March 2020.”

Long-term unemployment

The benefits of minimising immediate job losses are clear; workers without jobs consume less as their incomes fall, further exacerbating the economic fallout. There is a more worrying consequence than immediate job losses, however. Past recessions have shown us that a percentage of those who lose their jobs may struggle to find another job even years down the track. And the effect appears to be much worse when there is a long, slow economic recovery rather than a strong rebound.

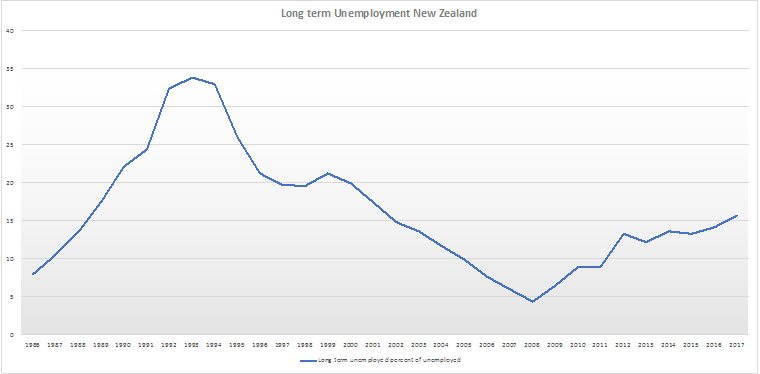

Long-term unemployment is particularly a risk when cyclical unemployment (for instance, from a recession) meets structural unemployment (when the worker’s skills don’t meet the needs of the current market). Long-term unemployment grew sharply in New Zealand from the mid-1980s, but since then has been falling, finally recovering to previous levels by 2000. That is, until the GFC hit in 2008.

Data source: OECD

The social costs of losing this connection to work is very high. A review of research in Quartz magazine points to evidence that long term unemployed are five times more likely to be living in poverty than their employed counterparts. Even when they find a new job they tend to earn less than they were previously and often take a step down the career ladder.

There is no doubt the wage subsidy scheme was necessary and hopefully will have flattened the potential unemployment curve just as New Zealand’s actions on the public health front have effectively squashed the pandemic curve. The final tally though, in terms of the implications for businesses and workers, is so far unclearbut will be felt for years to come.

*Alison Brook is from the Knowledge Exchange Hub at the Massey University campus at Albany, Auckland. She is on the GDPLive team. This article is a post from the GDPLive blog, and is here with permission. The New Zealand GDPLive resource can also be accessed here.