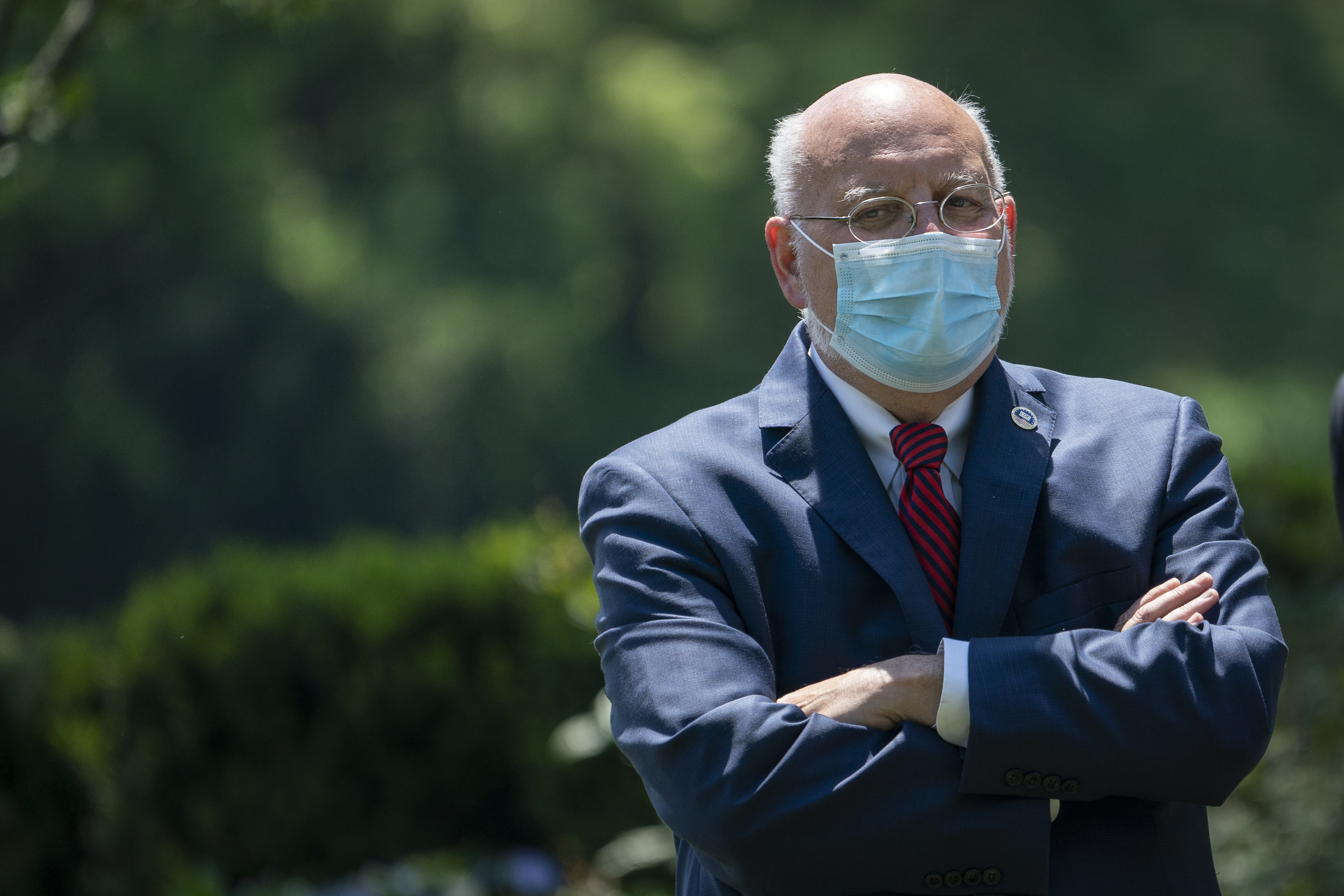

Getty | Drew Angerer

CDC says its testing fail didn’t hurt US response. Experts disagree

Experts say better public health infrastructure, more testing would have helped.

by Beth MoleThe botched rollout of COVID-19 testing did not cripple the country’s early response to the pandemic, the director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention claimed Friday.

CDC Director Robert Redfield cited a new analysis published by the agency Friday. The analysis suggests the new coronavirus began spreading in the country in late January or early February—but only at low levels. The study appears in the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

With the new data, Redfield argued that the level of spread was so low in those early days that additional testing would not have made a difference in detecting the spread of the pandemic virus. If the CDC had initially produced and scaled up a functional test for COVID-19—which it infamously failed to do—“it really would be like looking for a needle in a haystack," Redfield said, according to NPR.

Puzzlingly, he also claimed that new analysis proves the country’s outbreak surveillance systems are effective at detecting outbreaks early. The analysis drew from four lines of evidence: genetic sequences of SARS-CoV-2 isolates, testing done as part of routine influenza surveillance, emergency room records, and information on two early deaths in California that were retrospectively determined to be due to COVID-19.

"We had pretty good eyes on it," Redfield said of the outbreak. "And the availability of having a diagnostic didn't change our ability to do the surveillance."

Experts were quick to dispute Redfield’s claims. Michael Mina, an infectious disease expert at Harvard, told NPR that, contrary to Redfield’s claims, the data “demonstrates the need for large scale-ups and improvements to public health infectious disease surveillance.”

Likewise, Jennifer Nuzzo, an epidemiologist at Johns Hopkins, noted that "no one is arguing that the US should have done widespread testing in January,” as Redfield seems to suggest. But, “we should have done targeted surveillance testing... We still don't know precisely when COVID-19 was first introduced or how many people were infected. The only way we would have been able to know this is if we had been testing more broadly.”

The US is now one of the hardest-hit countries in the world, with more COVID-19 cases and deaths than any other. This week, the US passed the grim milestone of 100,000 deaths.