‘A broken piece of jade’: the turbulent future of Hong Kong

The city’s unique role as a halfway house between China and the rest of the world is now under threat

by Xinning Liu, Nicolle Liu, Tom MitchellFor four decades Hong Kong has thrived as a perfect middle ground between China and the US.

Independent courts and free information flows made the city a base for everyone from US investment bankers advising Chinese state companies to supply chain managers dealing with low-cost factories just over the border in Guangdong province.

Since Beijing’s economic reforms began in 1978, Hong Kong has played a unique role — a place where western businesses could dip their toes in the new Chinese economy and where China’s Leninist system could engage with the modern, globalised economy.

For the past year, that lucrative position has been hanging by a thread. To the consternation of Beijing, a wave of pro-democracy protests, sometimes violent, regularly brought large sections of the city to a standstill, including, on one occasion, its airport, one of the busiest in the world.

Two new shocks now threaten to completely derail Hong Kong’s status as one of the world’s great financial, commercial and media centres — and place the city in the middle of the increasingly fractious relationship between China and the US.

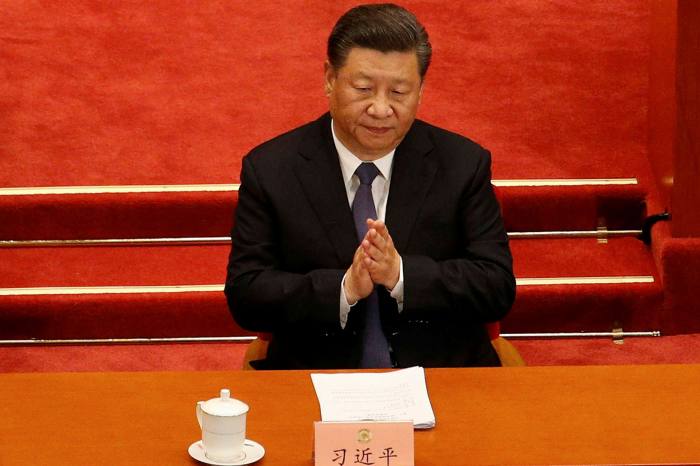

On May 21 China’s parliament, the National People’s Congress, announced it would impose a strict new national security law on Hong Kong. In response, US secretary of state Mike Pompeo on Wednesday said the city’s promised autonomy under a 50-year “one country, two systems” arrangement had been fatally undermined.

Mr Pompeo’s statement means that the former UK colony could eventually lose the various economic and trading privileges it currently enjoys with the world’s largest economy.

Felix Chung, a pro-Beijing lawmaker in Hong Kong’s Legislative Council, says he does not understand why a foreign government that professes support for the people of Hong Kong is punishing the city. “If you need to fight with China then just fight with China,” he argues. “Why are you messing up Hong Kong? It is like two adults in a fight accidentally hitting a child.”

Mr Pompeo said his hugely symbolic move “gives me no pleasure” but was unavoidable. “No reasonable person can assert today that Hong Kong maintains a high degree of autonomy from China,” he said. “While the US once hoped that free and prosperous Hong Kong would provide a model for authoritarian China, it is now clear that China is modelling Hong Kong after itself.”

China’s foreign ministry called Mr Pompeo’s remarks “imperious” and “solid evidence [of US] ulterior motives to play Hong Kong as a card and use it as a frontier for secession, subversion, infiltration and sabotage activities against the mainland”.

Hong Kong’s pro-democracy protesters have responded to Beijing’s power play with defiance. One of their most popular slogans is a uniquely Chinese variant of Patrick Henry’s famous US revolutionary war cry: “Give me liberty or give me death!”. On placards held by black-clad front-line protesters, or scrawled in handwritten notes pinned to the backpacks of young students, protesters have declared that “it is better to be a broken piece of jade than an unbroken ceramic tile”.

Renewed opposition

Hong Kong’s benchmark Hang Seng index has fallen almost five per cent since the NPC’s announcement. The sell-off reflects fears ranging from resumption of widespread protests — which tapered off after the coronavirus pandemic but have been rekindled over the past week by the new national security law — to a longer-term erosion of the territory’s legal system.

Steve Tsang, director of the China Institute at Soas in London, predicts new protests and a harsh response over coming months as the national security law is “rammed through against the wishes of a very significant portion of the local population”.

Recommended

Instant InsightJamil Anderlini

Hong Kong is the battleground in a US-China cold war

“For many people in Hong Kong such an act will be tantamount to ending the ‘one country, two systems’ model,” he adds. “We will now almost certainly see an upward spiral of protests and violence that will make the events of 2019 look restrained.”

Although many of the details about how the new national security law will be implemented remain unclear, it has the potential to fundamentally alter the nature of Hong Kong.

Simon Pritchard at Gavekal, an investment consultancy, says one longer-term effect of the new law “may be a change in [Hong Kong’s] legal culture expressed by the Chinese construct of ‘rule by law’ . . . over and above ‘rule of law’, which makes all actors including the government subsidiary to the law.”

“Hong Kong may not be a democracy,” Mr Pritchard adds, “but it has been a rare jurisdiction in Asia where an individual can sue the government and stand a fair chance of winning.”

In the short term, the risk to Hong Kong is a slow trickle of multinationals and financial firms deciding to relocate their Asian headquarters. Singapore is likely to try and attract more companies, while the UK has announced a plan that could potentially lead to millions of Hong Kong people gaining citizenship.

In a worst-case scenario, foreign executives could end up having to worry about being arrested in Hong Kong on vague national security grounds. Two Canadians, Michael Kovrig and Michael Spavor, were held in China in 2018 in retaliation for the detention in Canada of Meng Wanzhou, a senior executive at Chinese telecommunications Huawei, pending her possible extradition to the US.

“Definition and details are really necessary to alleviate a fear factor developing in the business community,” says Tara Joseph, president of the American Chamber of Commerce in Hong Kong. “A Beijing inspired national security law leaves open an interpretation of how such an act will be enforced . . . People may also ask whether Beijing’s concern over foreign interference adds an element of risk to foreigners living here.”

Chinese and Hong Kong government officials counter that such fears are overblown. The legislation, they add, will help put an end to a protest movement that has hurt the economy. Gross domestic product in the territory fell 3 per cent year on year in the second half of 2019.

Many business and financial professionals agree with Beijing. Last Sunday Lawrence Chan, a 41 year-old finance executive, fumed as he sat in his red Ferrari sports car, stuck at a roadblock erected by protesters in one of Hong Kong’s busiest shopping districts. “The protesters are irrational,” he told the Financial Times. “I am not worried about the national security law because I go to mainland China all the time for work. If I am not worried about travelling to China, why should I be worried in Hong Kong?”

Johannes Chan, a legal scholar and former dean of the University of Hong Kong’s law faculty, argues that official assurances about the law are short-sighted. “From the beginning, Beijing's understanding of ‘one country, two systems’ has been ‘one country, two economic systems’, and they don't want anything else,” he says. “But Hong Kong’s economy doesn’t work like that. You can’t have economic success without also political freedoms and all the basic values that flow from that.”

‘We must fight on’

Whatever the economic implications of the new law, Hong Kong is now on the cusp of another phase of political confrontation. The pro-democracy protests were initially triggered by a controversial extradition bill that would have allowed the city’s residents to face trial for certain offences in China.

Hong Kong’s chief executive, Carrie Lam, eventually acknowledged defeat but her belated withdrawal of the bill was not enough to assuage the protesters. Instead they upped their demands, including democratic elections for the territory’s top leader. Hong Kong’s chief executive is currently installed by a 1,200 member “election committee” stacked with pro-Beijing establishment figures.

The Chinese Communist party has never been able to accept the possibility that the protests reflect the real aspirations of a majority of Hong Kong residents for greater democracy. In the party’s lexicon the protesters are simply “not patriots” and cannot be trusted to vote for a chief executive acceptable to Beijing.

“Competition between China and the US is fiercer than ever,” says one Chinese legal scholar who advises the central government on Hong Kong issues and asked not to be named. “Some people in Hong Kong feel that they have to pick sides and want to draw a clear line between themselves and China. But as a part of China, they cannot just turn their back on their home country.”

“[China is] afraid of Hong Kong people power. We must fight on,” Jimmy Lai, a former fashion entrepreneur who went on to establish the city’s largest pro-democracy newspaper, said in a series of tweets over the past week. “Hong Kong shares the universal values [of] freedom and democracy . . . it is the bridgehead for [a global] ideological battle.”

Mr Lai, who is awaiting trial for participating last year in a peaceful march that did not have police authorisation, this week urged US President Donald Trump to pressure his Chinese counterpart Xi Jinping “to reconsider this disastrous course of action in Hong Kong”.

“The Chinese Communist party hates [US pressure] because they know it hurts them,” he told the FT. “If we lose our rule of law and freedom, we will have nothing left.”

Additional reporting by Sue-Lin Wong in Hong Kong