Opinion

Dominic Cummings and Boris Johnson have wrecked something precious

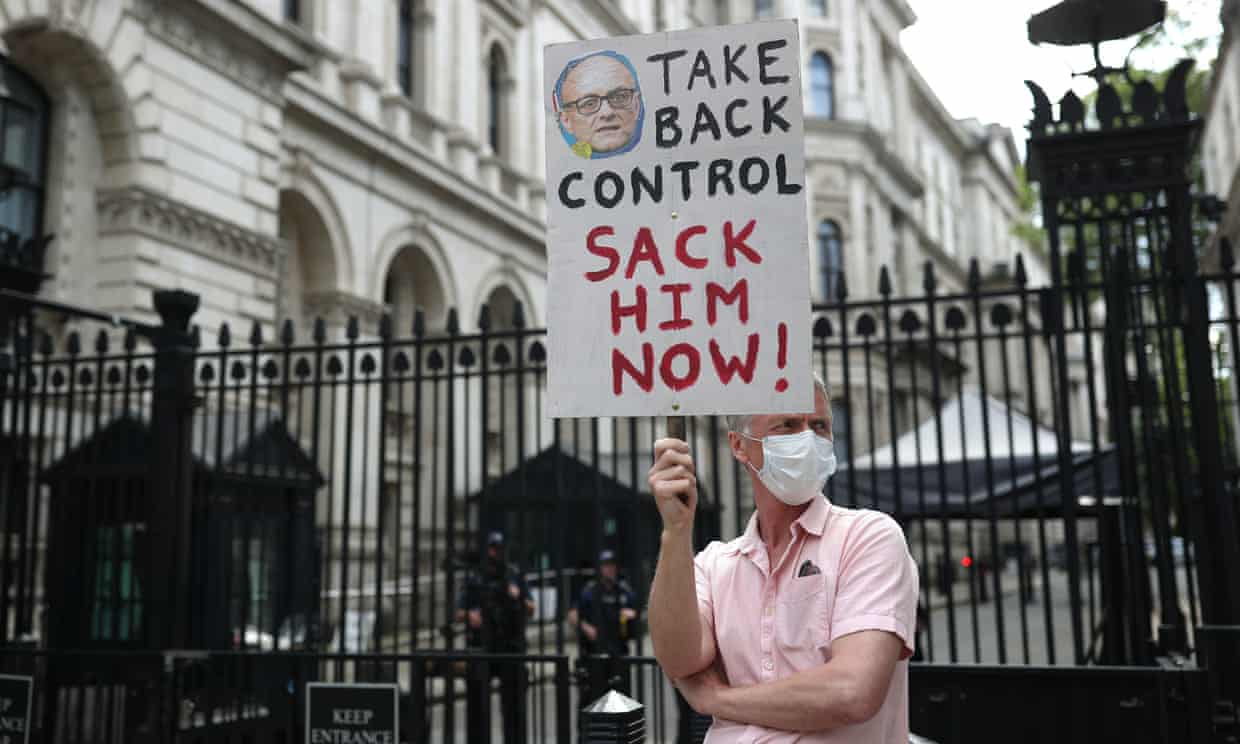

Their actions may damage the Tories’ political prospects, but the real victim is the British people’s trust in those in charge

by Jonathan FreedlandLook around, survey the rubble and consider what damage has been done these last seven days. The government, the prime minister and the man who gives both their instructions have all degraded themselves. In the process, they have destroyed something that mattered more than any of them – something unspoken but precious.

Start with the man who wrought this ruin. Dominic Cummings has ruled chiefly by fear, making Downing Street his personal “court”, according to one former minister. His power to intimidate derived from his status as the electorate whisperer, a man uniquely able to hear the vox populi, his brain tuned to the wavelength of the great British public when everyone in the SW1 bubble was stuck on the wrong frequency. Of course, that Benedict Cumberbatch TV depiction only added to his lustre: politicians wilt before one of their own who acquires celebrity. For proof, look no further than the rise of Boris Johnson.

So marvel at the irony that a man who made his name denouncing hypocritical Westminster elitism and its contempt for ordinary people is now the face of it. The king of data can spend this weekend crunching the numbers of a Daily Mail poll that found him wholly out of step with the very public he was supposedly so gifted at reading: 66% think he should quit, 63% think he should be sacked, 78% don’t believe a word of his yarn about driving to Barnard Castle to test his eyesight. The electorate are not whispering now: they’re yelling in his face.

Even if he stays, whether for just six months, as he reportedly intends, or longer, he is diminished. Diminished morally, of course, not that the parliamentary Tory party will care about that, but also as a diviner of public sentiment. As of now, there is no one more out of touch with the great British public than him.

The taint of Cummings’ behaviour has spread to every cabinet minister who defended him, telling the nation that Dom’s only crime was loving his family too much – and so implicitly telling every Briton who obeyed the rules that they loved their family too little. Each one of them is shrunk by this.

Naturally, the politician most wounded is Johnson. He has insulted the very people who voted for him last December, whether one-time Labour voters or lifelong Tories. Anyone who followed the rules has reason to be livid. No wonder one Tory MP, a former minister, told me in despair this week: “This is a cabinet of fools led by a hollow narcissist who is nothing without his svengali.” Some of those who glimpsed Johnson’s physical mortality in April sense they’ve seen his political mortality in May.

For all that, the prime minister’s defenders are adamant that he can ride it out. The government has a majority of 80 and it won’t face the electorate again until 2024, by which time Barnard Castle will be on a multiple-choice pub quiz question, alongside Specsavers and Dollond & Aitchison.

That might be right, but it rests on an assumption that political memories fade. Usually they do, with only nerds and obsessives remembering most of the flaps that grip Westminster. But not always. Sometimes an event cuts through so sharply, it sculpts an image of a government in the public mind that never shifts.

The exemplar is 1992. A matter of months after winning an election, John Major’s government trashed its reputation on Black Wednesday – and it remained trashed. Then, too, the Tories told themselves that they had five years to turn things around, but they were wrong. The economy improved, growth returned, but it made no difference. From Black Wednesday on, the government was in a slow-motion descent towards the abyss of 1997.

It’s no stretch to believe that this period will similarly define this government. If we hadn’t been talking about bluebell woods this week, we would have been gripped instead by the fact that Britain now hovers between the highest and second-highest per capita death rates from Covid-19 in the world, with an excess deaths figure that in absolute terms is the highest in Europe and second only to Trump’s America globally.

You don’t even have to relitigate the early decisions – the delayed lockdown, the release of infected patients from hospitals into care homes – that proved so fateful and fatal. You merely need to judge the government’s performance right now. It could be the flailing and floundering of Johnson before Wednesday’s liaison committee of MPs, a prime minister clueless as to the policies of his own government, or Thursday’s move to ease lockdown restrictions even as the chief scientific adviser warned that new infections are coming at a rate of 54,000 per week, a figure that, in his words, “urges caution”.

Which brings us to the real victims of Cummings’ actions. Not him or his bosses and their political careers – but the British people. What Cummings did wrecked public trust, turning us cynical about instructions from those in charge. Public trust is not merely a political commodity: in a pandemic, it is an essential public health resource. And now it has been badly depleted.

So when the health secretary, Matt Hancock, tells Britons it is their “civic duty” to isolate if they’re identified as a contact of someone who’s tested positive, the natural impulse will be to laugh in his face. Civic duty indeed. Tell that to Cummings. Now an essential public health message has to be qualified and caveated to accommodate Cummings’ behaviour. Isolate – unless your “instincts” say otherwise. Isolate – unless childcare gets a bit tricky. It doesn’t quite carry the same force, does it?

It may be that, if it wants to be effective, the government should step aside and let others carry this message. No more Hancock or Johnson or Michael Gove. Let the instructions come from the NHS and NHS officials alone. People might follow the advice of senior doctors and scientists if there’s no minister standing alongside them, because they at least will be free of the taint of this soiled administration.

Of course, that could only ever be a partial solution, because in a major crisis we need an effective government, and now we don’t have one. There is a deeper loss too, even if it is less tangible. In those first few weeks of lockdown, there was a rare spirit of collective endeavour and solidarity – the sense that, while it was hard to be away from beloved friends and cherished family, it was necessary and, above all, it was not a hardship borne alone. We were all in this together. That, beyond gratitude to carers, was what so many were expressing every Thursday night at 8pm.

Cummings and the defenders of Cummings have ruined all that. They’ve made too many feel like mugs for taking their deprivation so literally, when really it was only ever optional. Beyond the political fallout and the effect on public health messaging, this is where much of the current anger comes from. Together, we had created something precious in the midst of all this death and sorrow – and those in charge have made a mockery of it.

• Jonathan Freedland is a Guardian columnist

Guardian Newsroom: The Dominic Cummings story

On Wednesday 3 June at 7pm we’re holding a live-streamed event exploring the ongoing controversy of Dominic Cummings’ lockdown-defying road trip and the government’s handling of the ensuing fallout. With the Guardian’s deputy national news editor, Archie Bland, Guardian columnist Jonathan Freedland, and the Observer’s chief leader writer, Sonia Sodha.

Book tickets here