Surviving Childhood and a Plastic Nightmare in Psychological Horror ‘Pin’ [Formative Fears]

by Paul LeFormative Fears is a column that explores how horror scared us from an early age, or how the genre contextualizes youthful phobias and trauma. From memories of things that went bump in the night, to adolescent anxieties made real through the use of monsters and mayhem, this series expresses what it felt like to be a frightened child – and what still scares us well into adulthood.

Every childhood is different.

While they may grow up together under the same roof, siblings are not guaranteed to have identical experiences. Factors like age, gender, and culture are all crucial when shaping young minds; other influences like parental affection and discipline are just as important to consider. Filmmaker Sandor Stern explores this concept of coexisting yet disparate childhoods in Pin, a frightening tale of how a brother and sister came of age under the care of callous parents.

Adapted from a 1981 novel by Andrew Neiderman, Pin chronicles the young lives of Leon (David Hewlett) and Ursula Linden (Cynthia Preston). Their unusual journey begins with a flashforward – neighborhood kids dare one of their own to get a close-up look at the solitary, motionless figure who sits by an upstairs window in the Linden house – before shifting things to the past. Fifteen years earlier, in the same dull home where luxurious furniture is covered in plastic protectors, the well-to-do Lindens fulfill their nightly rituals. Once Leon and Ursula finish their snacks, their mother (Bronwen Mantel) immediately vacuums the crumbs off the floor. Their father (Terry O’Quinn) sends his children to bed after having each one complete a tailored math exercise: five-year-old Ursula merely counts to ten, and seven-year-old Leon counts backwards by sevens from one hundred. The Linden family appears fortunate to a casual observer. They want for nothing possession-wise as the father is a successful doctor; the mother keeps their home spotless. Looking beyond the surface, though, one will find there is something peculiar about the Lindens.

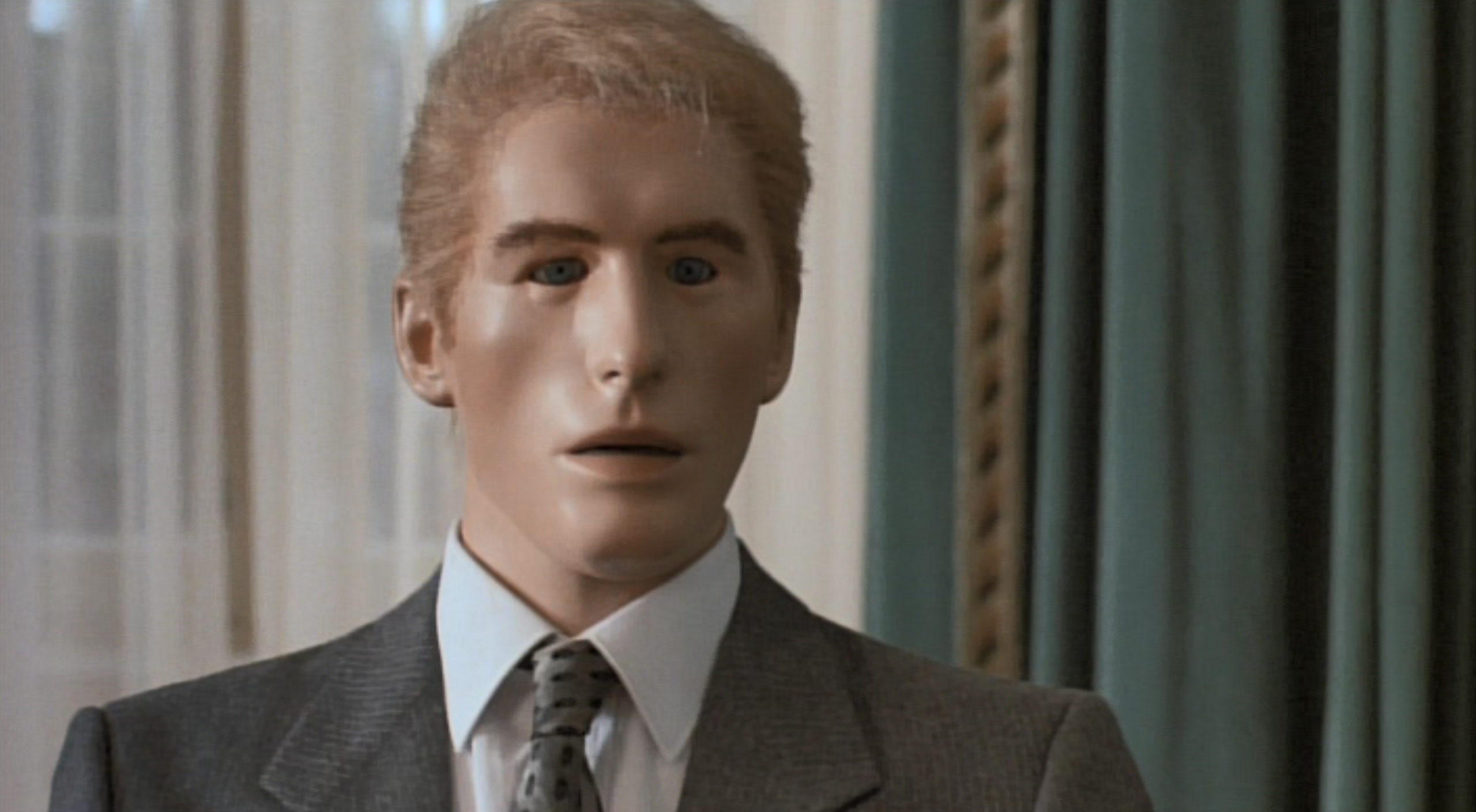

In place of direct parenting, Dr. Frank Linden relies on a custom-made Transparent Anatomical Manikin affectionately known as “Pin” (short for Pinocchio, as his “nose never grew ’cause [he] never told a lie”). At any time the patriarch wishes to share life lessons with patients or his progeny, he looks to Pin for help. Leon and Ursula often sit down with the medical doll in their father’s office, and, through the use of ventriloquism, Dr. Linden gives Pin life (in reality, he’s voiced by Jonathan Banks). Ursula catches on to her father’s trick, but Leon is far more naïve. Whenever his sister insinuates Pin is in fact inanimate, Leon reacts as if Ursula is committing blasphemy.

The differences between the Linden children become increasingly apparent as soon as the good doctor teaches them about the birds and the bees. This is only after the mother finds an 11-year-old Ursula with a pornographic magazine. Staying true to his character, Dr. Linden lets Pin do all the talking. Leon is visibly uncomfortable with the lesson – he previously witnessed his father’s nurse using Pin as a makeshift sex aid – whereas Ursula gladly removes the doll’s modesty towel. As the children later discuss the “biological need” Pin spoke of, Leon states he’s too young for that; Ursula “can’t wait to be old enough” as she imagines she’s “really gonna like it.”

High school is where the source material and the film start to diverge. What distinguishes the two is Leon’s movie depiction–he is utterly apathetic towards socializing. His literary counterpart at least had a few adolescent trysts before distancing himself from everyone. In contrast, both Ursulas embrace their burgeoning sexuality. Her newfound reputation at school has left Leon panic-stricken; the thought of her being intimate with anyone sends him into a rage that speaks to his own emotional difficulties with sex. As Ursula surrenders to the “Need” with various classmates – the Linden siblings regularly call their libidos this in the book – Leon shows no sincere interest in any woman that isn’t his sister.

After catching her with a boy during a school dance in the movie, Leon forbids fifteen-year-old Ursula from having any more sex. Which is why coming to him with news of her unplanned pregnancy is so difficult. Leon’s immediate reaction is to ask Pin for advice. And, much to Ursula’s horror, Pin responds despite their father not being present. She realized long ago their imaginary friend was nothing more than an illusion, but Leon still thinks otherwise. Ursula eventually has no choice but to tell her father the truth; they agree to “take care” of the pregnancy on a Sunday afternoon when the doctor’s office is closed. Dr. Linden’s approach is mercilessly unfeeling, almost as if he’s more bothered by the fact he has to come in on his day off. He even asks his son if he would like to watch as though this was an educational opportunity.

The ordeal understandably affects Ursula, who has abstained from even dating in the days that follow. Their mother was clueless as to what happened; Dr. Linden didn’t want to trouble her. This trend of secrets continues up until his and his wife’s deaths. After finding Leon talking to Pin – and hearing the manikin reply – the doctor is so shaken up that he crashes their car. Among the wreckage, Leon discovers Pin, who the father haphazardly stashed away in the backseat in a desperate attempt to be rid of him. Scenes like this lead viewers to wonder if Pin is as lifeless as he appears to be. Whatever the case, Leon is relieved that his “real” father survived the accident, and he takes him home where he belongs.

Having to care for themselves and each other all those years, Leon and Ursula are borderline impassive about their parents’ death. The first thing they do after the funeral is rip the plastic off the furniture and eat junk food; they quickly find solace by defying their mother’s compulsive cleanliness. Aunt Dorothy (Patricia Collins) invites herself to stay, but Leon makes quick work of her by using Pin to scare the old woman into a heart attack. With no one else around, Leon finally has Ursula all to himself. That is, until his sister meets a handsome college student named Stan (John Pyper-Ferguson) at the library she works at. His sudden appearance makes Leon feel threatened, and he believes he has no choice but to remove Stan from the picture.

By now, Leon’s relationship with Pin has become pathological–he’s made him up to look more human, he’s dressed him in their father’s clothes, and he seats him at the dining room table during meals. Ursula is not oblivious to her brother’s mental state; she’s read every psychiatric book at the library. Yet, no matter what he does – such as reciting an original poem about a man raping his sister – Ursula refuses to have Leon committed like Stan suggests. She tearfully vows to stay by his side, as he would with her, despite coming to the painful conclusion that her brother may be a paranoid schizophrenic.

Stern was unable to use the original ending from the novel because of the film’s low budget. Even so, his reworking is a more optimistic approach. The entire screenplay is an astounding modification of the source material, whose more lascivious moments were omitted from the movie. Instead, the director emphasizes the emotional bond between Leon and Ursula. The new tone retains the brother’s frame of mind as well as adds a whole other layer to him–his repression has made him sympathetic much like the character of Mark Lewis in 1960’s Peeping Tom.

The unbearable truth about their childhood blindsides Leon near the climax when Ursula remembers their father’s math quizzes: no matter how Ursula answered her question, she was rewarded like a pet. Leon’s own memory – the doctor would never think to overlook any mistake his son made – is less fond. The Linden adults substituted love with sterility and avoided conflict at any cost; the outcome was two children who had no choice but to find acceptance and guidance wherever they could. Even if that meant projecting their desires and needs onto a life-sized doll. In essence, the Linden children are two sides of the same damaged coin. Although Ursula overcame her adversities and escaped, Leon succumbed to a fate provoked by years of neglect and trauma.

Pin is full of persuasive performances and memorable setpieces. The movie has found a faithful following since its initial release, albeit an often apologetic one. The movie’s themes are never quite illicit – especially compared to the novel – but the sentiment is there without having to look too hard. As some people will find the story too uncomfortable to watch, others cannot help but be fascinated by Leon and Ursula’s unique and resilient kinship.