You Can't Afford Bad Investments

by Wolf ReportSummary

- This is another article that's not about specific companies, but about investment mentality and lessons in how to structure yourself when investing.

- This, I believe, is as or more crucial than investing in the right stocks or investment options.

- In this article I show you the price of investing in unsafe or poor businesses, and the price it has with regards to your goals.

Now, before going deeper into this article, I want to preface it with a few things that I want everyone to remember as we go through these things.

1. Everyone makes investment mistakes.

The title of the article isn't "How to not make mistakes". I'm not saying that you won't make investment mistakes. You will. The purpose of the article is to highlight the results of investment mistakes and hopefully giving you some inspiration on how to avoid them.

The fact is though, no one bats 100 out of 100. We all make mistakes. So let's minimize them while remembering why we can't afford to make them.

2. Your investment mistakes forge you from low-grade pig iron to high-grade steel.

Mistakes teach us, in everything. The purpose here is again, not to think we won't make mistakes, but to minimize the impact of them and make certain that the learning experiences don't result in massive losses of capital.

3. A good investor isn't made overnight.

I consider myself extremely lucky. I've yet to make a mistake that results in the loss of more than 0.15% of my available capital/portfolio. Given the time I've been active - around 10-12 years - I know people who have quite literally lost over 95% of their portfolio during recessions and speculative investments. That being said, I'm far from the authority on anything - and I have decades to go yet. As do likely most of you. Learning takes time. The aim is to minimize mistakes made on the way.

Now let's get going.

(Source: Payday Solo)

Why you can't afford bad investments

If you're anything like me, you're probably interested in investing in dividend-paying stocks for some type of financial flexibility or freedom going forward. It can be anything from wanting to extend your monthly income with the passive proceeds from great dividend stocks, to the goal that I reached 2018/2019 - complete financial independence from gainful employment - at least in theory, and in my current geography.

(Source: F.A.S.T graphs)

This term is, of course, entirely subjective. I may be financially independent given my current circumstances and desired living conditions - but another individual may not. Independence depends on your personal circumstances - not just your current circumstances but your desired circumstances. Were I to have children, which certainly is the norm, or want a third house, the equation would change.

I'm personally not one of the people content living on $600/month out of a refurbished van - though I applaud those that do, and like the lifestyle myself. My own desired circumstances are more mainstream - house, average lifestyle, discretionary spending funds to live the life I'm "used to". I was lucky enough to run into dividend investing "theory" very early on in my investment career. Early enough that, I've never been undiversified in my investments to the degree that some have. This, among other things, has helped me on the way.

In the end, the core of why I've rarely or never invested in, or invested significantly in any significant loss-making or excessively risky stock is simple - math.

The math of losses

You've probably heard before about the damage a loss can cause to your portfolio. But let's put it in numbers so that you know why going forward, I make some of the arguments that I do.

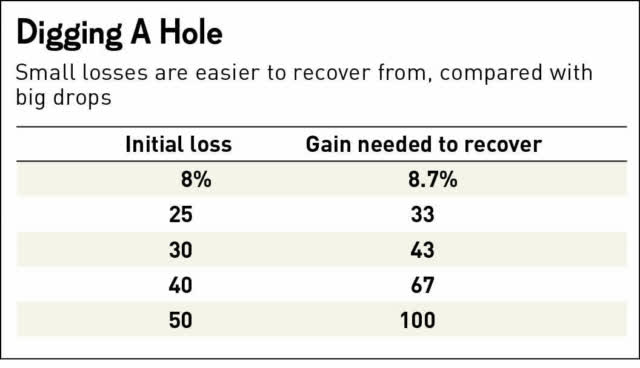

Upon calculating percentages, which is what we do in investing, we start off with a base value. The base value of stock X is $10. Going up 10%, it's worth $11. Going down 10% from the base value of $10, the value would be $9. This would take it to a new base value, from which the required growth in terms of percentages, simply to recover your loss from $9 to $10, would be 11.1%.

This is the back-biting we encounter in loss-making, and why as the year's gone on, I've become more and more conservative, more and more careful in my investments. It's extremely basic, yet observing people in their investment behavior, I question whether they truly consider the underlying math before putting hard-earned money into unsafe investments.

If you've passed basic-level math, you know that increasing losses transform required rates of return from 11.1% from a 10% drop, into massive differences, such as a drop of 25% requiring a 33% gain simply to get back to your break-even point. Let's play some more with these numbers, just to really hammer this home.

(Source: Investor's Business)

A 50% drop? 100% required gain.

80%? 500% gain simply to get back to your base value.

The reason I bring up 50-80% losses, which some may say are unrealistic, is that it's been proven as little as 1-2 months ago that 50-80% losses across entire sectors aren't at all unusual. Take the mREIT industry. The oil industry. The coal industry (in the longer term). The hotel industry, car renting, and the car industry. All of these sectors have seen massive losses, and most haven't even come close to the beginning of recovery as of yet.

The fact is this. Whenever you make any investment into any sort of stock, bond, or investment, you need to ask yourself and really make yourself face the potential of the bear thesis materializing. Very few people came close to expecting Shells (RDS.B) dividend cut - or the way Occidental Petroleum (OXY) has been going on the market. When investing, you should always consider the worst-case scenario, no matter how unlikely or foreign it may seem to you or the company - because no one can foresee what will happen. No company is truly safe.

And when bad things inevitably happen to your portfolio, this math is what makes certain that your road to recovery, in direct proportion to your percentage of total invested capital in the investment, will be a horrendous one.

Saving and/or gambling isn't investing

There's a marked difference between saving - the process of putting money aside in a safe place -, gambling - overreaching with more money than you can afford, overexposure or unsafe investments (or simply lottery gambling) - and investing.

(Source: Casinobeats)

As humans, we have a tendency to overreach and both desperation and exuberance magnify this trait to worrying proportions. I've seen both seasoned and new investors fall victim to this. Investors that:

- Put tens of thousands of dollars into bitcoin because it rose before, only to have it fall more than 80% within a year.

- Overexpose to any particular stock, often risky but touted safe, to a 20-50% exposure, only to suffer massive losses.

- Don't know what they invest in, which means they don't know when they should invest more, invest less, or get out.

Just a few examples. The point here is this, you need to differentiate between the three, know what you're doing. Saving is usually easy. Any time you're putting the money in a government-insured account, your mattress or anything of the sort, that to me is saving. Even putting your capital in the broadest index fund you can find doesn't constitute saving to me, that's investing.

(Source: US News & World Report)

My view is that smart investors do both - save and invest. I will always hold a certain small percentage of my capital, depending on the annualized cadence and amount of my cash inflow, in either cash or what to me as a private individual is cash-equivalents (Immediate lines of credit, credit cards, bank savings, cash in my wallet, etc.). In my current situation, my view is that I need no more than 0.75% of my total capital available to me at a moment's notice, but this may change going forward.

However, one thing I've taken with me from working for years with higher-net worth individuals. None of them gamble. Ever. Oh, they may play a game of poker for a few bucks or go to the track now and then. But when it comes to investments, all of them are chronically conservative individuals. When I speak to new investors, or when people contact me to ask on how to allocate/manage money, they often do so with the expectations of extreme returns and extreme risk tolerance.

I believe there are reasons for why higher-net worth individuals are one way, and the latter is the other way.

"Invest only what you can afford to lose"

I don't like this expression.

While it correctly encapsulates the notion that you should expect the stock market to be inherently volatile, it incorrectly can give investors the mentality that permanent loss of capital as a result of the investment is in any way an acceptable outcome.

Expecting to make mistakes and lose money is not the same as not learning from them. I see too many investors putting their money to work in high-yielding, unsafe stocks, and investments, only to grow angry when the investments don't work out. They then repeat the exact same process in a different, albeit similar-quality investment without a change to their process, expecting a different outcome - the definition of insanity.

Every investment mistake should be a poignant lesson - regardless if you lose $50 or $50,000. My harshest investment lesson was an investment of around $790 in 2019, and this loss still hurts to think about today, despite my portfolio being valued in the hundreds of thousands/millions. The fact is that the expression above indicates that anyone ever has "money that they can afford to lose". Even those people that I know with extremely high net worth don't have "money they can afford to lose". That's not how responsible people handle money, regardless of their personal level of wealth. This is actually a truly bad, wrong, and perceptually incorrect piece of advice.

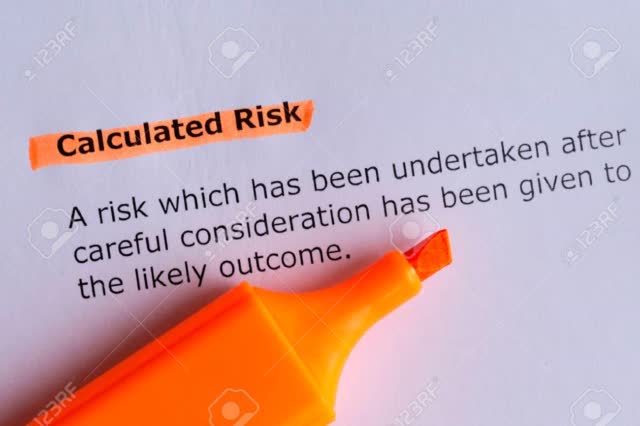

(Source: 123RF.com)

This ties into why you can't afford to think of invested money as something "you can afford to lose". Think of your invested capital as money where you're willing to take calculated risks. You have your savings - the amount you need to live day-to-day, but then you have the money you expect to grow. That's money you can't afford to lose - we can't ever afford to lose money - but you're willing to take some risk to see it grow.

The notion of "only investing what you can afford to lose" equates investing in stocks to gambling. I don't gamble. I invest, and that's why I own a portfolio of dividend-paying stocks, without being over-exposed to anything, but actively managing my assets in a way that, until now, has provided me with superior returns.

Why you can't afford NOT to invest

I know equally many people, including close family, who've stayed out of the market most of their lives - they always view it as too risky, too overvalued, not clear what they should invest in - the excuses are numerous and equally hollow.

(Source: Pinterest)

Here are some thoughts on why you can't afford not to invest in the market.

- Increased Inflation in costs of living coupled with a lack or insufficient amount of salary inflation inevitably erodes your purchasing power over time and guarantees that, without investing, you will likely never achieve any measure of financial independence or long-term security. Interest-rate savings accounts today don't even provide enough gains to beat the CPI (Consumer price index) over the long term.

- I don't believe that anyone under 35 years of age (that includes me) today in the western world - that includes Sweden - will be able to get a state pension we can conceivably live on. Even today, pensioners in Sweden (one of the more socialist countries) are poor, and the math going forward no longer works out. So we can either hope for a miraculous solution from the government, or we can take our fate and long-term finances into our own hands. I choose the latter. In Sweden we have a flexible pension system - running my own company, I do everything I can to minimize government pension contributions and instead pay me in a way where I control the capital from the get-go (salary, dividends, etc.) and there are no withdrawal clauses. In Sweden, we call this future danger the 40-40-40 problem. That means you work 40 hours a week for 40 years, to then live on 40% of your salary. There is no proposed solution for this, and it only gets worse as time goes on.

- Living costs going forward are likely to only get higher and higher, with wage inflation unlikely to change given the dynamics of the job market - more people available, more automatization, and less available possibilities for everyone/more competition. This is inevitable. It's been going on for at least 90 years, and it continues to this day.

These things alone should, if not scare you, at least make you think. To me, it's part of why I consider a 3% safe yield and capital appreciation much better than a 7% "relatively safe" yield, and why I indeed focus more on safety than yield. I could never adopt an income-method style sort of investing, given the massive risk of capital loss.

The factors above mean that it's typically far harder to contribute new capital to your investment plan than it is to invest in safe alternatives from the get-go and minimize your overall risk profile.

So - while you can't afford to make bad investments, you also can't afford, as I see it, to not invest. The result of this is that unless you have a trust, an inheritance or already are independently wealthy, you'll likely not have the life you want for yourself.

Start thinking - Start investing - Take Calculated Risks

Too many people listen blindly to others and how others do things. I think that while Warren Buffett is a finance guru, the latest crash has shown quite clearly that Buffett with all his experience, can fail as much as us mere mortals can.

When I write articles on stocks or general articles like this, I don't want readers or investors to take the message as literal - instead, I want to spark consideration on how to think about investments or these things and how they relate and can fit into your life and your goals.

I do think certain things transcend individual prerequisites. For those investors who followed my advice and have avoided overexposure to any one particular stock or sector, they have usually done quite a bit better than investors who did not. My strategy involves a high amount of diversification into individual securities to where no single holding amounts for more than 5% of my total portfolio - and fewer than 8 holdings are above 3.5%. While this caps my upside, it also does wonders when compared to investors who went into this market with a high exposure to singular stocks - usually, this exposure was to Oil, REITS, or similar companies, which have fared very poorly in this environment thus far.

There are, beyond the points in this article, a few things I recommend. Research & Read is one of them. Know what you invest in, know it as well as possible. While you may have investors you trust to know a certain sector or business - and I have this too - it's important to not just trust blindly but also do your own homework. Diversify is the second one, coupled with don't overexpose your position, which of course can be done in a variety of different ways. Get paid is another piece of advice I consider universal. My interpretation of this point is to make certain that investments pay dividends, but it can be interpreted differently as well. Be aware of risks is perhaps the most important piece of advice to give investors of any level of experience, even if for most of us this is little more than a reiteration.

You can't afford bad investments - that's the title of this article. The reasons for this are many but include simple math and fundamental societal changes that indicate the future will be far harder than expected. The fact is that "bad" or sub-par investments outnumber good investments in the market, which together with the other reasons is why you need to be careful when investing. Recovery from a poor investment takes a long time, and involves many potential headwinds.

Furthermore, if you're building financial safety starting from $0, it's even more important as I see it that you embrace safety and conservative risk-taking as one of your creeds. Few things make me more uneasy than seeing a pensioner wanting to diversify savings and pensions into a basket of 10-25% yielding securities/bonds with the argument that "this way, they get the income they need".

As I see it, your goal should never be to "get rich quick" or reach the goal quickly in any way - that way lies ruin. Conservative, undervalued investments dictate their own rates of return, and these are facts one must accept, not try to change through including higher yield and higher risking securities in a senseless manner.

The fact is, if you don't diversify, if you're not risk-aware if you don't have a strategy that suits your goals, if you don't know what you're investing in, you're quite likely to end up a very certain way.

Poor.

I think we can all agree that we want to end up the opposite.

I hope this piece provided some food for thought - as putting it on "paper" certainly provided the same for me.

Thank you for reading.

Disclosure: I am/we are long RDS.B. I wrote this article myself, and it expresses my own opinions. I am not receiving compensation for it (other than from Seeking Alpha). I have no business relationship with any company whose stock is mentioned in this article.

Additional disclosure: While this article may sound like financial advice, please observe that the author is not a CFA or in any way licensed to give financial advice. It may be structured as such, but it is not financial advice. Investors are required and expected to do their own due diligence and research prior to any investment.

I own the European/Scandinavian tickers (not the ADRs) of all European/Scandinavian companies listed in my articles.