Illustration

A comic for Covid-19: the tale of a plague-hit Derbyshire village

Nick Burton’s Our Plague Year draws eerie parallels between Eyam in 1665-66 and today – complete with self-sacrifice, selfish second-homers and confusing public messages

by Hettie Judah‘Know what’s been bothering me since the lockdown? Nobody trusts nobody no more,” says a long-haired young man, building a wall (or perhaps a tomb). “Everybody’s like, ‘Don’t come near me bro, you might have the infection.’” But this isn’t lockdown Britain – nor indeed lockdown anywhere in 2020. It’s the Derbyshire village of Eyam during the 1665-6 plague outbreak, as imagined by artist Nick Burton in the exquisitely doomy new comic strip Our Plague Year.

Burton has a flair for the bittersweet. The two-page comic Lily that he showed in the Manchester Open Exhibition at Home last year was a romance between a bicycle and the woman who first rode it. Recalling Lily, Bren O’Callaghan, the curator of Home, contacted Burton in March asking if he might consider producing a comic “addressing some of the themes that were prevalent in our society at the moment”.

Home will release new episodes from Our Plague Year on its website every Friday from 29 May (the impatient can subscribe to an email that will reach them two days earlier.) “Each is a vignette that dips into a small moment,” says Burton, who has built up enough plot and material for Our Plague Year to stretch to 100 episodes. A book seems likely. God help us all if the serialisation is extended and we reach that many episodes while still under lockdown.

Researching similar events throughout history, Burton came across the story of Eyam, a village in the Peak District that famously isolated itself from surrounding communities after the Black Death arrived in a cloth delivery from London. “You could immediately see the connection with what was going on in our society,” says Burton, who notes the irony that, although he’s just constructed a dramatic universe around Eyam, circumstances dictate that he’s never set foot in the actual village.

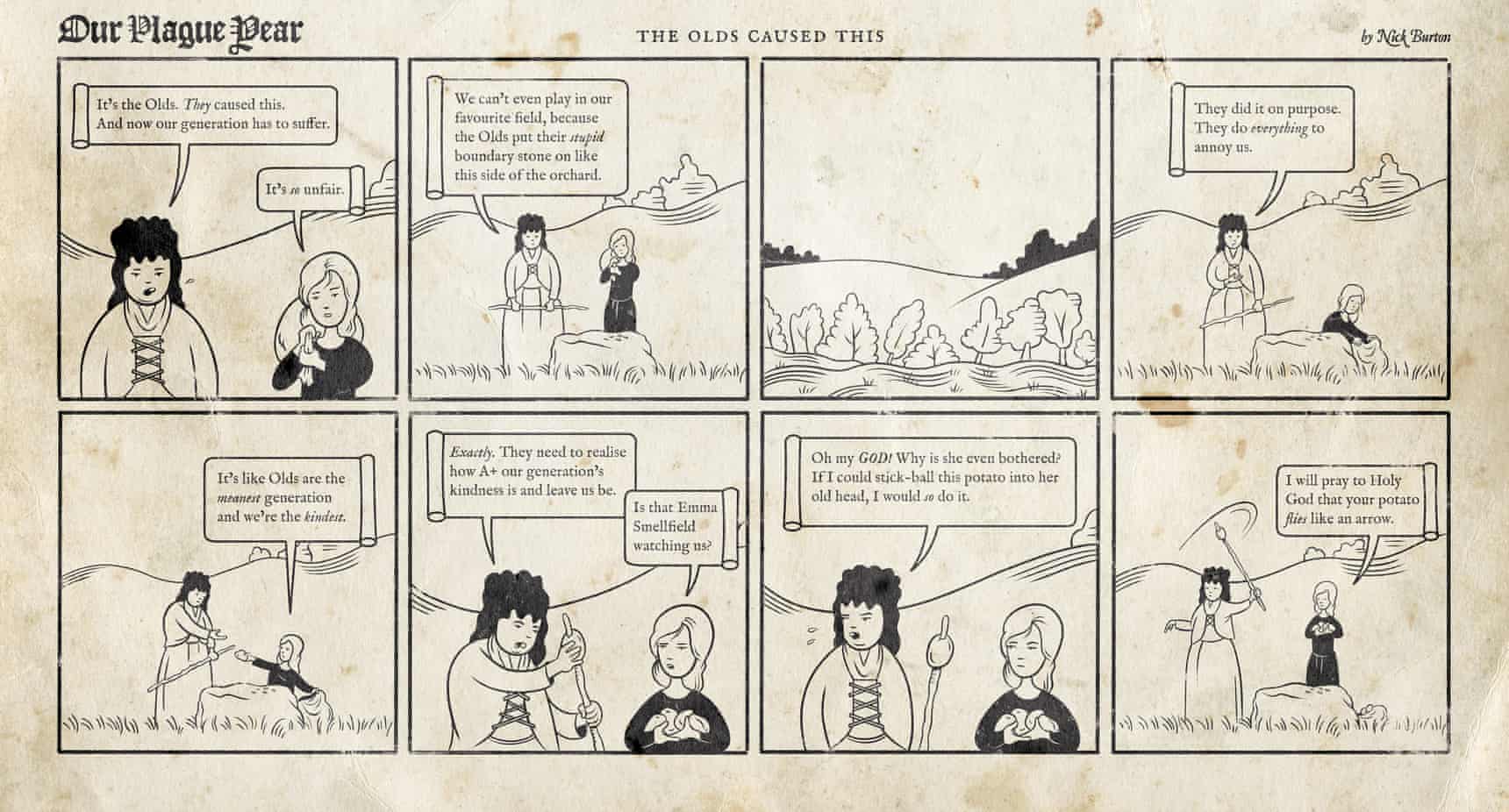

It’s no bad thing that the setting of Our Plague Year exists only in Burton’s imagination as “an alternative-world Eyam”. It frees him to redraw phenomena of our present time as historical fiction: a population struggling with confusing guidelines from on high; nosy neighbours avidly policing local behaviour; kamikaze amblers using bodily proximity as a threat.

“It is 100% about the human reaction to tragedy,” says Burton. Perhaps because he started work on the series in the days when British shoppers were voraciously locusting loo paper, “it looks at the more selfish side of these reactions”.

As those of us whose childhood was scarred by Raymond Briggs’s harrowing evocation of nuclear apocalypse When the Wind Blows can testify, comics can have devastating impact. “It’s a great medium for addressing these horrible events – they’ve done it for centuries,” says Burton, who cites William Hogarth’s A Harlot’s Progress as an early antecedent. He likens the comic artist’s role to that of a jester who can needle the king and escape with his head still attached: “Because people don’t take them seriously you can get away with commentating on serious events.”

Drawn as lockdown continues and moods shift, Our Plague Year can marry the long narrative arcs of a graphic novel with the responsiveness of a strip cartoon like Peanuts or Doonesbury, which are more “read one day and in the bin the next”, notes Burton.

The parallels with plague-beset Eyam are darkly, comically real. “Just like today, we’d have some people who adhere to the lockdown and others that think it’s ridiculous,” says Burton. He describes how the wealthier residents of Eyam swiftly departed for other residences, and how the boundaries of the village were policed.

Contemporary conspiracy theorists may be wigging out over 5G towers and secret labs in Wuhan; the residents of Eyam looked to the superstitions of their own time for the source of their suffering. “It was the end of the age of magic and the beginning of the age of science,” says Burton. “So you still had people blaming the fairies for it: they were such capricious, evil creatures in those days, people were scared of them.”

The most touching evocation of Eyam has happened on Burton’s own doorstep. William Mompesson, the vicar of Eyam, closed the church and instead led his congregation to worship in the open, by a rock called Cucklet Delf. With the synagogue shut in Burton’s Salford neighbourhood, the local rabbi has become equally inventive. “I live in a three-storey flat here, and my kitchen window looks into an open space bounded on all sides by townhouses and flats,” he says. This space, usually populated by kids and trampolines, has become an ad hoc synagogue, a Cucklet Delf for our times: “The rabbi in the middle, and everybody in their windows reading from the scriptures.”

- The first episode of Nick Burton’s Our Plague Year is out now.