Hidden Cost of Mass Layoffs: Why Job Cuts Won’t Solve States’ Budget Crisis

States and cities are slashing jobs in the face of huge deficits. But making the budget math work isn’t quite so simple.

by Brandon KochkodinIn Ohio, Governor Mike DeWine froze hiring. New York’s Andrew Cuomo halted raises for 85,000 union workers, including police and corrections officers. In Pennsylvania, 9,000 state employees stopped getting paychecks.

And it’s just the beginning. While over 40 million jobs have vanished during the pandemic, states have held off on firing workers en masse. Yet as they reopen, huge deficits caused by Covid-19 mean layoffs are all but certain. Deciding who — and how many — will lose jobs will require tough choices and have devastating consequences for those affected. On Thursday, New Jersey Governor Phil Murphy said the state may have to fire 200,000 public workers.

But using job cuts to make the budget math work won’t be so simple.

That’s because what might seem like a straightforward cost-savings strategy is anything but, according to former state budget officers. Not only is there severance pay for accrued vacation and sick days, but also provisions that let some former employees, like those in Virginia, keep their health-care plans for up to a year. Crucially, every laid off worker adds to the burgeoning rolls of the unemployed, putting states’ nearly depleted unemployment trust funds under even more strain. People who lose their jobs also spend less, depressing tax revenue. And fewer public workers mean fewer public services.

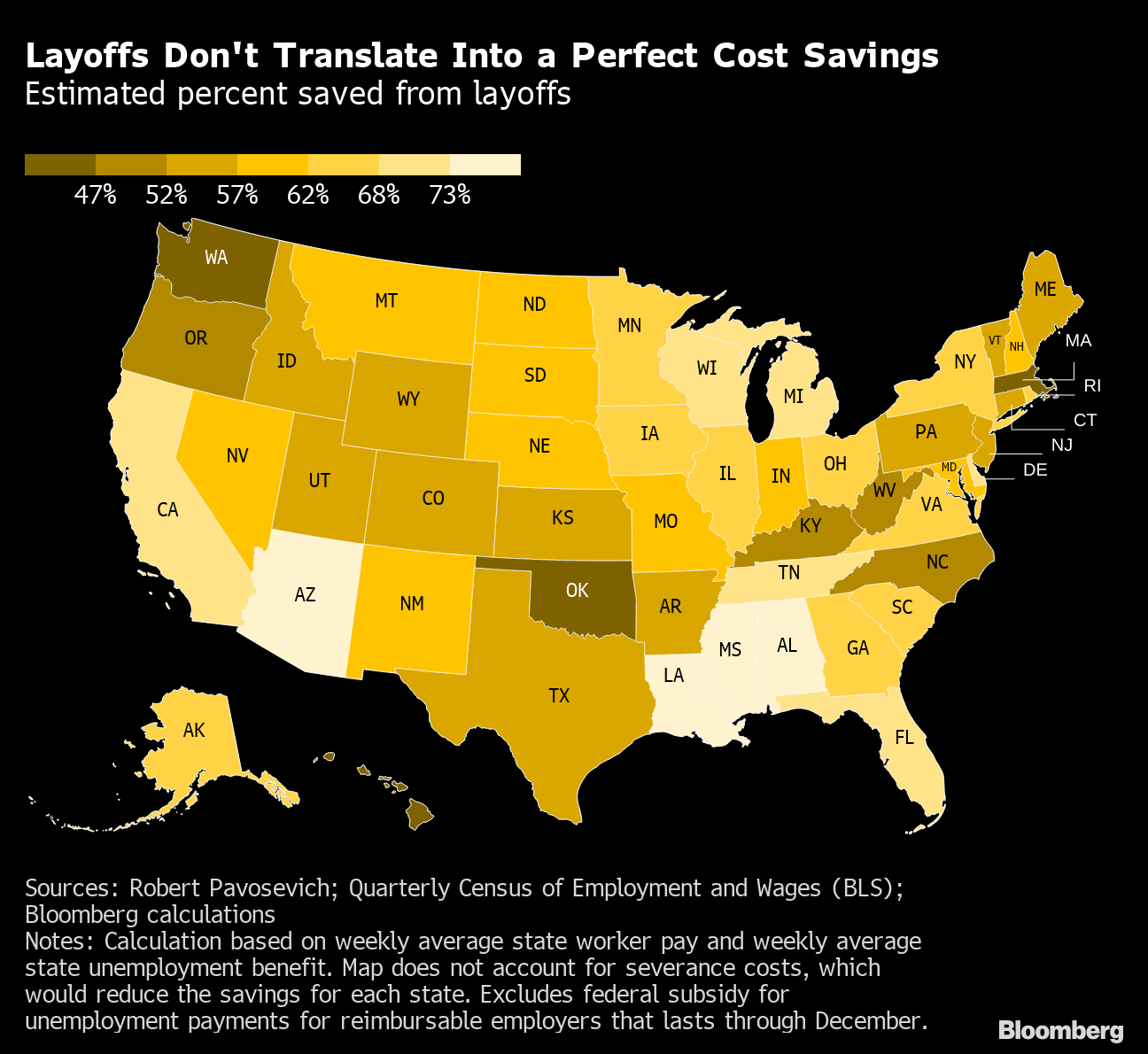

In all, for every dollar in salary, the savings can be as little as 33 cents in the first year, according to Bloomberg calculations based on data from the Labor Department and figures provided by Robert Pavosevich, the lead actuary at its Office of Unemployment Insurance before retiring in 2019.

“Unlike other cuts, layoffs aren’t a 100% cost reduction,” said Scott Pattison, former executive director of the National Governors Association and a former state budget officer for Virginia. “It’s not as if you make a clean break where you make the layoffs and then don’t have any additional costs.”

States’ multibillion-dollar payrolls make them a crucial economic driver, and aid to cash-strapped local governments is a centerpiece of House Democrats’ $3 trillion stimulus bill to prevent further job losses. Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell and other senior Republicans say there's no immediate urgency to act.

Read More: N.J. May Have to Fire 200,000 Public Employees, Murphy Says

With 46 out of 50 states starting their new fiscal years in July, layoffs are only a matter of time, according to Pattison. A recent estimate by the National League of Cities suggests between 300,000 and nearly a million workers in cities across America could lose their jobs or be furloughed.

For states that are already borrowing to plug holes in their budgets, the cuts will have to run deep. Consider the state of Texas, where its Workforce Commission has already asked to borrow $6.4 billion to cover jobless benefits through July after nearly depleting its unemployment trust fund, according to the Tax Foundation and a local news report.

A full-time state employee, on average, had a weekly wage of $1,153 per week, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. If that person was laid off, the state’s weekly unemployment benefit would pay roughly $507, based on a calculation provided by Pavosevich. As a result, Texas would only save 56 cents for every dollar of salary that is eliminated. And that doesn't include any costs associated with severance. (If you include the Trump administration’s pledge to subsidize half of the states’ unemployment insurance costs, the savings rises to 78 cents.)

In states like Hawaii, Kentucky, Massachusetts and Oklahoma, the savings would be less than 50%, the data show.

Complicating the Equation

That’s not all. Complicating the equation is the fact that, because jobless benefits usually only cover a portion of an out-of-work state employee’s lost earnings and don’t include health benefits, displaced workers often end up having to sign up for food stamps or Medicaid. So the immediate savings is borne as a cost to the state somewhere else.

Then there are the fiscal consequences that arise when income- and sales-tax revenues plummet just as social-welfare spending surges, says Shelby Kerns, the executive director of the National Association of State Budget Officers.

“States employ about 20 million workers and they spend money too,” she said. “When you lay off state workers, you shift costs on both ends because of lost income and sales tax receipts that they don’t pay.”

Pavosevich points out that America’s unemployment system was designed to be countercyclical — meaning employers would bear the costs of unemployment insurance in good times. But that’s only true for what’s known as contributory employers, those who pay into the system as they go. Most businesses fall in this category. That’s not the case for reimbursable employers, which primarily consist of cities, public agencies and nonprofits. They choose to pay back any unemployment benefits that their laid-off workers receive as they are incurred.

But because the decline in economic activity has been so sharp and the job losses so widespread, local governments and nonprofits may simply not have the money to pay back the states, adding to the stress on their unemployment funds that are already nearing insolvency.

“It’s a large bill that will come due to state and local governments and nonprofits in the next quarter following layoffs,” Pavosevich said. “State governments are going to have to finance that in some way. I think most states will go broke.”

The impact goes well beyond mere dollars and cents. Steep reductions in the public-sector workforce are coming at a time when many Americans need their local governments’ help the most.

Fiscal Bind

Dozens of communities from Dayton, Ohio, to Houston and Monterey, California, have announced they’ll be forced to lay off or furlough workers, and scores more have reduced or eliminated key public services, with more to come, according to data compiled by the U.S. Conference of Mayors. Education, sanitation, safety and health could all be at risk, leaving the public-safety net in tatters. What’s more, nonprofits, who often shoulder the burden of assisting the neediest, are themselves struggling to make ends meet, says David L. Thompson of the National Council of Nonprofits.

“If nonprofits had the money, they wouldn’t lay people off in the first place,” Thompson said.

The fiscal bind has already spurred some states to petition the federal government for more aid. California, New York and Texas have sought tens of billions of dollars in government loans for their unemployment trust fund accounts. Pavosevich expects that states will lobby for the federal subsidy to be extended beyond December.

“I don’t think there’s any amount of cuts or any amount of taxes that begins to fill the hole,” Murphy told Bloomberg Television, adding that without federal aid, state and local governments will have to dismiss firefighters, police, emergency-medical personnel and others.

Yet there’s also a risk that some elected officials may use the current crisis as political cover to purge public-sector payrolls beyond what’s fiscally necessary to advance certain policy priorities, according to Tracy Gordon, a senior fellow at the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center. Broad-based cuts could leave critical public services understaffed just as the need soars.

“There is an opportunity to do this in a strategic and targeted way,’’ Pattison said. “But I fear many will simply do across-the-board cuts and layoffs.”

— With assistance by Edward Dufner