Commentary: COVID 'Immunity Passport' No More Reliable Than a Coin Flip

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

May 27, 2020 -- Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I'm Dr F. Perry Wilson at the Yale School of Medicine.

This week, my Twitter feed is filling up with talk about antibody testing.

Wouldn't it be nice to have a simple blood test and know that you are immune to the coronavirus? How liberating would it be to walk into the grocery store with your face mask—which you are wearing out of sheer politeness—hiding a self-satisfied grin. For you, the worst is over.

And yes, it would be great to give people confidence as they go back to work, go to summer camp, or patronize local businesses.

But there are a lot of caveats to antibody testing. Experts have rightly pointed out that just because you have antibodies against coronavirus, it doesn't mean that you have protective antibodies; you'd need a specialized viral culture test to prove that.

And the debacle of exempting antibody tests from FDA review has been well reported. But these are really not the biggest issues.

The biggest one—the most glaringly important one—is not getting talked about enough. It's the fact that a positive antibody test, in many cases, makes it about 50/50 that you actually have any antibodies against the coronavirus. It's the difference between the false-positive rate of a test and the positive predictive value of a test. These are different things. And, almost universally, test manufacturers report the former but don't discuss the latter.

But we will.

To show you what I mean, we're going to go through a simple thought experiment.

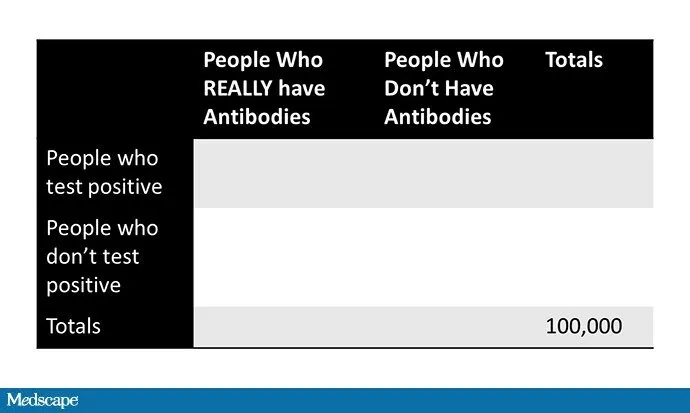

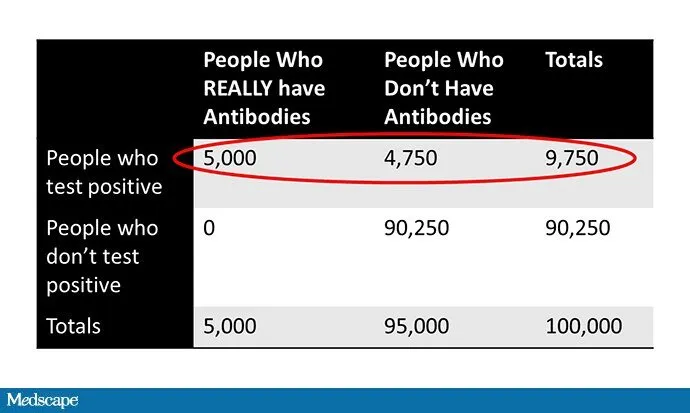

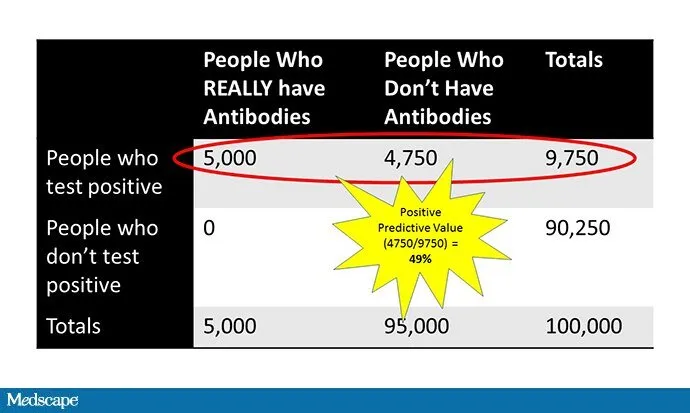

Imagine that we have a population the size of New Haven, Connecticut—roughly 100,000 people.

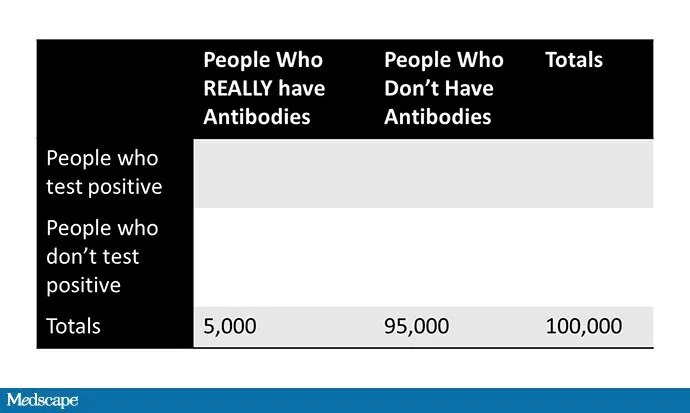

Let's say that 5% of the city has been infected with the coronavirus, survived, and has protective antibodies. That's 5000 people who are immune.

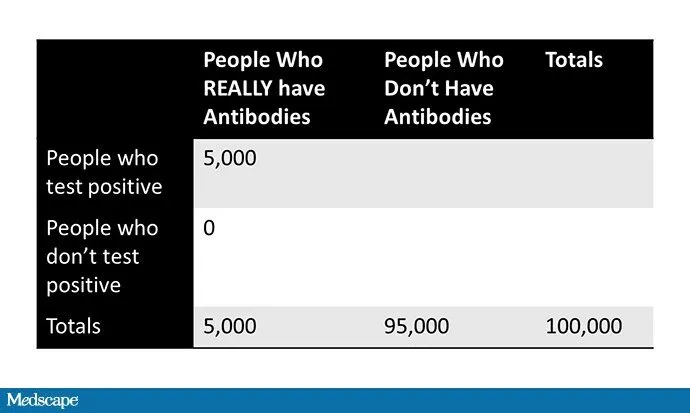

Now, let's test every single person in the city to see who has antibodies. Let's say that the test is 100% sensitive (unrealistic, but it makes the math easy); it captures all 5000 people who are truly immune.

But what if it's 95% specific, meaning a 5% false-positive rate? Doesn't seem too bad, right?

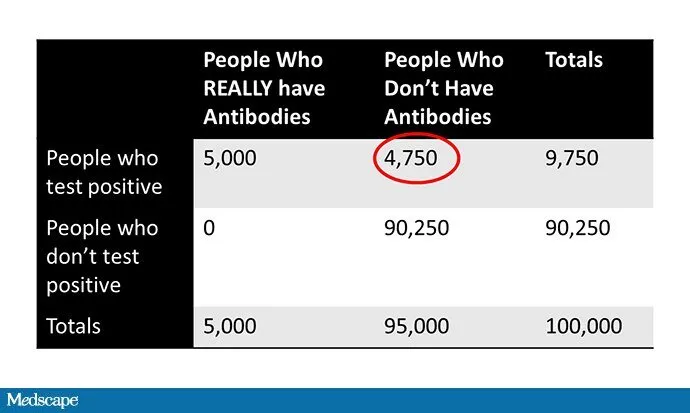

Well, that means that 5% of the 95,000 people who aren't immune—4750 people—will nevertheless test positive.

Okay. Now we have a total of 9750 people who tested positive, of whom only 5000—just over 50%—are actually immune.

That immunity passport you got is no better than a coin flip.

The positive predictive value is what it is despite the low false-positive rate because the underlying prevalence of the disease is still low.

This misunderstanding of the difference between false-positive rate and positive predictive value may seriously endanger people.

This is my wife. She's a brilliant surgeon.

On Friday, she got an antibody test as part of a clinical study.

She's interested in the result, particularly if it's positive. But she's never had typical symptoms, and the prevalence of coronavirus in Connecticut is probably still south of 5%. For her, like most people, a positive result won't be particularly reassuring.

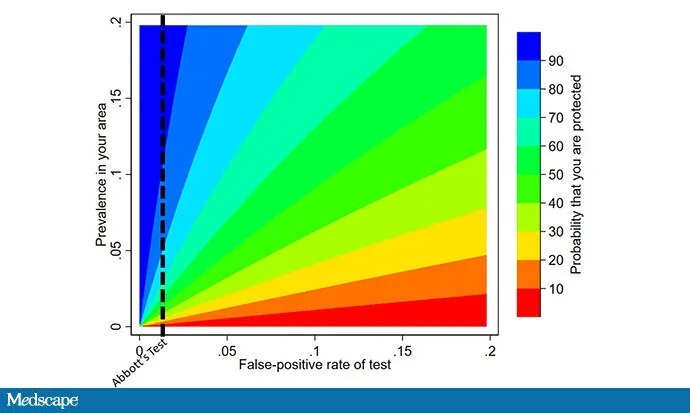

"Okay," you say, "but what if the false-positive rate of the test is even lower than 5%? What about 1%, or as Abbott claims with its antibody test, 0.4%?" I made this helpful graph since there is some favorable exchange rate between pictures and words.

As you can see, even with a really good test, if the prevalence in your area is low, you still have a good chance of not being protected. And, of course, there are a lot of tests going around.

Alexander Marson of UCSF and his team have been doing great work independently testing these antibody kits. Their results—it won't surprise you—tend to be worse than what manufacturers report, with false-positive rates ranging from 8.4% for the Decombio test and actual 0% for the Innovita test, though small sample sizes limit the precision of these estimates.

So here's the bottom line: Until there is good evidence that your local prevalence of coronavirus infections is somewhere north of 20%, using a positive antibody test as your ticket to not take the common-sense precautions we've all been taking is a recipe for disaster. It's just the math. Please spread the word before widespread availability of antibody testing leads to a bunch of bad decisions.

Oh, PS—yes, if you personally had COVID-19 or are very sure you had COVID-19, then it's more likely that a positive antibody test means you are protected. But for many of us, at least for now, that's not the case. There should not be antibody passports for a while.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale's Program of Applied Translational Research. His science communication work can be found in the Huffington Post, on NPR, and here on Medscape. He tweets @methodsmanmd and hosts a repository of his communication work at www.methodsman.com.

This article originally appeared on medscape.com.