No, Luckin Coffee Is Not 'Too Cheap'

by Vince MartinSummary

- LK stock has briefly caught a bid this week after falling over 95%.

- On paper, the numbers for LK can work at the current valuation, given cash on the balance sheet and even adjusting recent financials.

- But it's obviously impossible to trust the figures or management, the business model has real concerns, and a successful pivot would require pinpoint execution.

- Equity investors should take a cue from the bond market: LK stock has a real chance at hitting zero, even if it won't happen immediately.

There are investors out there who believe Luckin Coffee (LK) is too cheap, even considering the extraordinary circumstances surrounding the business. I sympathize with those investors — but I don't agree with them.

On paper, I can see a bull case. Luckin raised some $865 million in cash in January. At Thursday's close of $2.06, it has a market capitalization of $650 million. We don't have anything close to updated numbers, as Luckin still hasn't released fourth quarter 2019 results. But given disclosed balance sheet as of the end of Q3, as reported the company's cash, even net of debt, exceeds the current market capitalization.

Meanwhile, there is a business of some kind here. Luckin has admitted to a staggering amount of fabricated revenue. RMB2.2 billion in sales were made up, which is nearly half of total sales for the last three quarters of 2019 (including the midpoint of Q4 guidance). But the company's 4,000-plus locations still exist. So do millions of customers. And, presumably, Luckin can change tack after undertaking what literally might be the most aggressive growth plan in history. (Luckin went from zero stores to 4,507 locations in about 26 months.)

But the bull case seems far too simplistic. The balance sheet probably is in good shape, but at this point investors can't take any of Luckin's numbers purely at face value. That obvious issue aside, there's a very real concern as to whether the business model makes any sense — or can ever drive any profit. And it seems foolhardy, to say the least, to expect the company to pivot toward profitability after executing a massive and widespread fraud in a bid for growth.

To be sure, LK stock may catch a bid. I'm sure traders will have fun with the name, as they already have. (The stock has moved an average of 32% in six sessions since a six-week trading halt came to an end.) I'd expect volatile yet sideways trading to hold for at least the near future. But, as a long-term investment, it's incredibly difficult to make a reasonable, rational, case for LK stock, even 95% below the highs.

The Balance Sheet

In its third quarter report in November, Luckin reported that it closed the quarter with $775.6 million in cash. In January, it announced it had received total net proceeds of $865 million combined via a secondary offering (at $42 per ADS) and issuance of convertible debt.

There has been some cash burned along the way, however. The company reported free cash flow of negative 477 million RMB (~$67 million at current exchange rates) in Q3. Assume that rate held for the three following quarters through June 30th and Luckin would finish the second quarter of 2020 with something like $1.44 billion in cash. Debt was minimal at September 30 — about $33 million — and the convertible bond issue totaled $460 million.

In other words, Luckin could have close to $1 billion in net cash coming out of this year's Q2 — a sum roughly 50% greater than its market capitalization. That's an interesting point in favor of the bull case, or at least the "this is not a short to zero" argument.

Of course, that math may vastly oversimplify the situation. The obvious retort is that Luckin's cash balance (and cash flow) may be as fabricated as its revenue. In disclosing inflated sales, Luckin also said that "certain costs and expenses were also substantially inflated by fabricated transactions". There's not much reason why the fraudulent revenue and the inflated costs have to exactly net out. Free cash flow could have been much worse than -$67 million in Q3 — which means elevated burn in the eight months since the end of that quarter.

That said, there's likely still a significant amount of cash on the balance sheet. First, consider the source of the cash: equity and debt offerings (along with a private placement concurrent with the IPO last May) with total proceeds of $1.5 billion. Whatever an investor thinks about the role of Credit Suisse (CS) and Morgan Stanley (MS) in January's secondary offering, it's unlikely those firms wired the offering proceeds to the personal account of a Luckin executive or some shell company in the Cayman Islands. (A shell company besides Luckin, of course, which is incorporated in the Caymans.) I'd assume the cash from these heavily-publicized, widely-bought offerings actually reached Luckin's corporate coffers.

Second, the perpetrators of the fraud may have pilfered some of those funds — but they didn't have to. The point of the inflated sales was to show investors hypergrowth, which would inflate the LK stock price. That in turn would allow insiders (at least some of whom presumably had knowledge of the scheme) to either sell their shares — as happened in January, in a concurrent secondary offering — or pledge those inflated shares as collateral for loans. There's ostensibly not much reason to sneak money out the back door when you can walk out with it through the front door.

To be clear, I'm not suggesting investors can or should rely on the company's balance sheet and cash flow figures. The January secondaries were executed to raise funds for Luckin's so-called "smart unmanned retail strategy". But the anonymous author who wrote the prescient short report highlighted by Muddy Waters Research at the end of Jan. 31 cautioned that the raise could instead be "a convenient way for management to siphon large amount of cash [sic] from the company." That author highlighted alleged self-dealing at UCar, founded by Luckin chairman Charles Zhengyao Lu (also known as Lu Zhengyao), and suggested the establishment of a vending machine business by a related party could be a sign of similar activity at Luckin.

Still, the reported figures suggest Luckin should have net cash in the range of $1 billion at the moment — about $3 per ADS. It takes an awful lot of theft and/or self-dealing to get a material amount of that money out in the ten-plus months between the IPO (May 16 of last year) and the April 2 admission of fraudulent revenue. Even skeptics should believe that there's still a substantial amount of cash on the balance sheet. It's possible, and maybe even likely, that net cash per ADS is greater than Thursday's close of $2.06.

The Pivot

Whatever the exact amount of cash on the balance sheet, it seems like enough to buy Luckin Coffee some time. And the convertibles don't mature until January 2025.

Luckin Coffee should have enough cash to cover near-term burn. And it can change its strategy, pulling back sharply on its breakneck expansion and instead focus on profitability. And there's one key piece of good news on that front, from the F-1 filed in January for the equity offering:

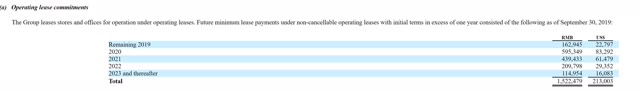

At September 30, Luckin's total operating lease commitments were only $213 million. The post-2022 figure is just $45.4 million. No doubt, both totals have risen — Luckin grew its store count 22% just in the fourth quarter of 2019 — but there's still a tremendous amount of flexibility here.

(An aside: it's possible the operating lease data too is faked. We obviously can't rely on basically any figure from Luckin, presumably save for the number of locations open. But for figures for which we have no disclosure of malfeasance and no apparent incentive for fraud, a reasonable working assumption is take the numbers at face value, if cautiously so.)

In considering the balance sheet and the operating lease profile, the bull case becomes apparent. I personally wouldn't be stunned if Luckin's actual net cash indeed is above the $2.06 per ADS price at the moment. (To be fair, little would surprise me about the Luckin story at this point.) The scheme wasn't likely solely about pulling cash directly out of the business. Even if that was an aspect of the effort, the perpetrators had little time to really get after the $865 million raised in January. And even if free cash flow burn was worse than reported, there's still a long way from the ~$1 billion net cash estimate at June 30 (using Q3 burn) to the $650 million market capitalization.

If that's the case, there might not necessarily be a floor under LK stock, but there's at least some time for the company to assess its options. Near-term bankruptcy ostensibly would be off the table. New management — the CEO and COO were fired this month — can look at real numbers and back off the 'blitzscaling' strategy. Thanks to what appear to be relatively short-term leases, Luckin Coffee can shrink relatively quickly to become a profitable and more normal (for lack of a better term) with potentially $1 or $2 per ADS in net cash on the balance sheet.

That likely suggests upside from $2.06 — and in a best-case scenario, potentially enormous returns. It's an attractive case on paper.

Is Luckin Coffee Profitable? Can It Be?

But the key words there are "on paper". There are a significant number of stumbling blocks in the way of that case.

One of the largest is the question as to whether Luckin Coffee's model actually is profitable at all. Even while recording fraudulent sales, Luckin as a whole wasn't. Non-GAAP operating loss in Q3 was RMB550 million, which actually rose year-over-year. Operating margins were -36%. The figures were slightly worse in the second quarter.

Those losses were justified as part of the growth strategy. CFO Reinout Schakel said on the Q3 conference call that the quarter saw "peak investments in sales and marketing". Luckin at the time targeted breakeven operating income at the company level by Q3 2020 as that spend receded. Meanwhile, store-level profits looked solid: Luckin claimed store level operating margins of 12.5% in Q3 2019. That was a huge (and in retrospect unsurprising) improvement from a modest store level loss in Q2.

If the average store already is profitable, and marketing spend is going to come down, then it seems likely that Luckin can be profitable at the enterprise level with a smaller footprint. Pick the best 1,000 (or 500, or 2,000) locations out of the 4,507 at year-end 2019, cut down on advertising and pre-opening spend, sharply reduce G&A, and there's got to be a pony somewhere.

After all, Luckin was reporting corporate-level operating losses during Q2 and Q3 — losses that actually increased year-over-year in both quarters. Wouldn't the perpetrators do more to boost profits and margins if that were the goal? As Luckin has said, expenses were inflated as well as sales were inflated. So some of that store-level profit might be false — but maybe not all of it.

But there's also a very real possibility that the unit economics here simply don't work. Since the IPO, bears have highlighted the myriad issues facing the business. Price points seem too low for the aggressive (and often-free) delivery offering. Chinese consumers still prefer tea, even with the arrival of Starbucks (SBUX) into their country. For all of Luckin's talk of being a 'tech' company, it's still a purveyor of low-price coffee, which usually is a low-margin business.

It's impossible to settle the debate at the moment without accurate and updated financials. But I'd highlight two points that undercut the bull case. The first is gross margin. It skyrocketed, as reported, expanding over 18 points year-over-year in Q3 and 11 points in Q2.

There are some fixed costs in that figure, but not much. (Labor and payroll costs are on a separate line item.) And so it's likely that the fraudulent sales inflated those margins. (Interestingly, the first question on the Q3 call was about the massive increase in gross margin, and in retrospect the answer from Schakel feels evasive.) And if reported Q3 margins were 900 bps higher than actuals — in other words, if half the expansion came from nonexistent revenue — then true store-level margins are under 5%. If that's the case, this business isn't really profitable considering corporate expense. Maybe a dramatic reduction in the company's free drinks policy finds a way around that problem, but plunging traffic causes its own margin issues.

The second issue comes from the aforementioned short report from late January. That report highlighted inflated sales. But it also highlighted inflated advertising revenue, claiming that third-party tracking showed that advertising spend was exaggerated by over 150%.

Why would the perpetrators do this? The author argues that the point was to create illusory store-level profit. That would keep the fiction going that enterprise-level losses were solely coming from the company spending on new, soon-to-be-profitable, locations, rather than from a structurally flawed business model.

It's impossible to independently verify the author's claims, though his or her credibility certainly is enhanced by the conclusions drawn elsewhere in the report. The author estimates a nearly RMB400 million boost to store level profit in Q3 — when Luckin reported RMB186.3 million in such earnings, with the help of inflated revenue. It's possible true store-level unit economics are disastrously unprofitable.

Management and Culture

If an investor believes, as I do, that the lion's share of the proceeds from the equity and debt offerings remain in Luckin's coffers, then perhaps even the operating model problem isn't insurmountable. If the company has $2-3 per ADS in net cash, it can lose a bit of money as it tries to find a new model. Capex should come down markedly from the $107 million reported through the first three quarters of 2019. Starbucks has done well in the market, even with delivery providing some margin pressure. If Luckin can do half as well, there's potentially upside in LK stock.

But it's worth remembering that investing is about businesses, not just numbers. (That is something I myself have forgotten all too often.) And this business is a mess. Again, the company inflated its revenue by something in the range of 100% for at least parts of three different quarters. It's now dealing with the aftereffects of the coronavirus pandemic in China, and a potential trade war, with its top executives gone.

Luckin's business model ostensibly rested on its technology. Indeed, when the company denied the allegations in the short report on Feb. 3, it pointed to its "robust" and "rigorous" internal controls over its data as a key reason why. Either the fraud was widespread enough, and reached high enough, to evade those controls, or the data systems are not what management has claimed. Neither suggests any real ability to trust Luckin Coffee going forward.

To be sure, it's possible Luckin Coffee finds its way out of this and creates some value at some point down the line. There are so many variables beyond the fraud, ranging from geopolitics to competition to the Chinese macroeconomic environment. And there is so much we don't know about the fraud, and what Luckin's actual numbers look like.

But what we do know is that nearly half of this company's reported revenue was fake. We can guess that the business is not, at the moment, profitable at the store level. It may not be close.

Top executives are gone, and the culture is questionable at best. As the Wall Street Journal reported this week, the company's chief financial officer wasn't actually in charge of Luckin's finance department last year. The two executives promoted this month both were senior vice presidents who presumably had no idea what was going on — itself a red flag in terms of management and communication.

Yet the bull case requires that this same company become a careful steward of shareholder cash; conduct itself with integrity; and dramatically change its focus from growth at all costs to profitability first. Simply put, that seems like far too much to ask.

Disclosure: I/we have no positions in any stocks mentioned, and no plans to initiate any positions within the next 72 hours. I wrote this article myself, and it expresses my own opinions. I am not receiving compensation for it (other than from Seeking Alpha). I have no business relationship with any company whose stock is mentioned in this article.