Trump is desperate to punish Big Tech but has no good way to do it

Trump's executive order shows how little power the president has over Silicon Valley.

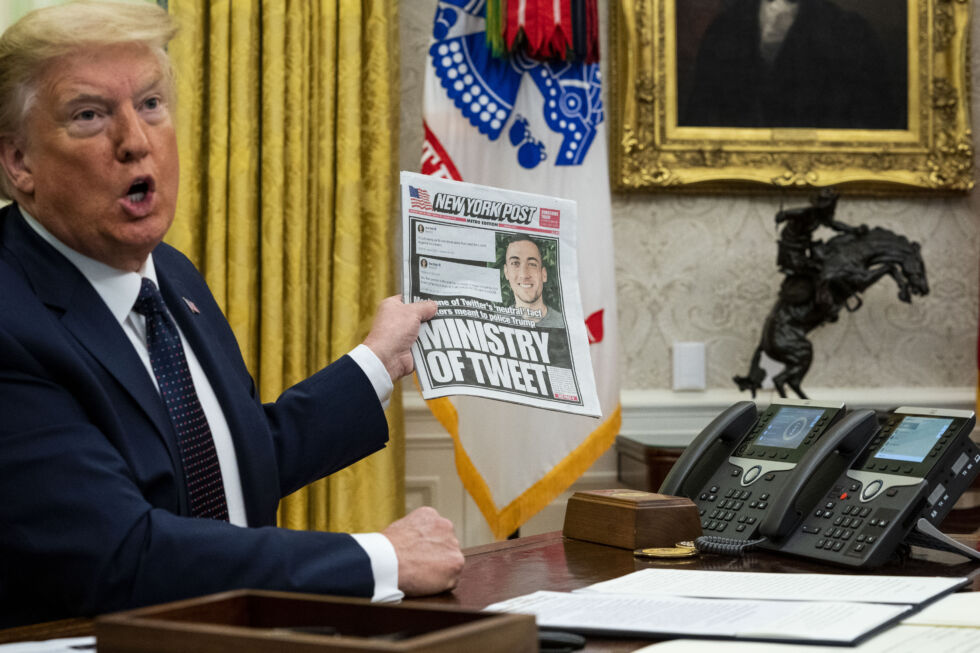

by Timothy B. Lee and Kate CoxDonald Trump is mad at Twitter, Facebook, and other big technology companies, and in an Oval Office statement on Thursday, he pledged to do something about it.

"A small handful of social media monopolies controls a vast portion of all public and private communications in the United States," he said. "They've had unchecked power to censor, restrict, edit, shape, hide, alter, virtually any form of communication between private citizens and large public audiences."

After his comments, Trump signed an executive order designed to bring social media companies to heel. But Trump has a problem: US law doesn't give the president much actual authority over technology companies. Indeed, the First Amendment arguably prohibits the federal government from second-guessing the editorial decisions of private companies like Facebook, Twitter, and Google.

Over the last year, Trump's advisors have been trying to cobble together a package of initiatives that would respond to Trump's desire for action against Big Tech while staying within the bounds of the law. On Thursday, the president finally signed the result of their efforts. It directs various federal agencies to take steps that penalize big technology platforms for perceived political bias.

Will this strategy work? We put that question to legal scholars and policy insiders in order to game out how the proposed executive order is likely to unfold in practice. While Trump portrays the executive order as the start of a titanic battle between the White House and big technology companies, the practical results may be much less dramatic.

The centerpiece of the order is an effort to strip big technology companies of protection under Section 230, a federal law that immunizes websites against liability for user-submitted content. That would be a big deal if Trump actually had the power to rewrite the law. But he doesn't. Rather, his plan relies on action by the Federal Communications Commission, an independent agency that has shown no inclination to help. Even with FCC help, the most that will happen is a slight reinterpretation of the law—one that the courts might choose to ignore.

The story is similar for other parts of Trump's executive order. Trump wants the Federal Trade Commission to ensure companies are following their own policies on content moderation. That's the same approach the FTC takes with privacy now, and it has proven toothless in practice. Perhaps the most significant change would be redirecting federal ad spending away from big technology platforms. At worst, that would be a modest hit to the bottom lines of technology giants that rake in billions of dollars every quarter.

Section 230: An “unprecedented liability shield”?

The centerpiece of Trump's executive order is a plan to reinterpret a 1996 law that has been instrumental in the growth of the Internet economy. Originally passed as Section 230 of the then-controversial Communications Decency Act, the law gives website owners and Internet service providers broad legal protections against liability for content uploaded by users.

Section 230 says that, for example, if an Ars reader leaves a comment that defames someone, Ars Technica can't be held liable for defamation. Similarly, YouTube, Facebook, and Twitter can't be sued based on the contents of their users' videos, posts, and tweets, respectively. The law also shields sites from liability if they decide to take down content that is "obscene, lewd, lascivious, filthy, excessively violent, harassing, or otherwise objectionable."

The idea behind the law was to promote the growth of the Internet economy while also making sure liability concerns didn't discourage platforms from filtering online content. Previously, some online service providers had taken a hands-off approach because they feared that removing some material would expose them to liability for content they failed to remove. Section 230 was described as a "good Samaritan" law, designed to ease these worries and enable online platforms to filter and moderate online content without worrying about the legal consequences.

Ironically, some pundits and politicians have turned this logic on its head—including President Trump.

"Social media giants like Twitter receive an unprecedented liability shield based on the theory that they are a neutral platform, not an editor with a viewpoint," Trump said in his Oval Office remarks on Thursday. "My executive order calls for new regulations under Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act to make it that social media companies that engage in censoring or any political conduct will not be able to keep their liability shield."

As anyone who has actually read the statute knows, this is simply not an accurate description.

"As the co-author of Section 230, let me make this clear: there is nothing in the law about political neutrality," tweeted Sen. Ron Wyden (D-Ore.), who co-sponsored the law as a young Congressman, on Wednesday.

To the contrary, the explicit goal of Section 230's authors was to free platform owners to make editorial judgments without worrying about the legal ramifications.

The authors of Trump's executive order seem to have a more sophisticated understanding of Section 230 than the president. Rather than peddling outright falsehoods about its content, the document attempts to narrow platforms' Section 230 immunity by focusing on a key requirement of the statute: that a decision to remove objectionable content must be "taken in good faith."

The order claims that social media companies are "invoking inconsistent, irrational, and groundless justifications" to remove content from their platforms. It argues that social media companies lie about their real reasons for removing content and that this means that their filtering decisions are not "in good faith" as required by the statute.

So what is Trump going to do about it? Here's where things get dicey.

Justin Sullivan/Getty Images

The FCC will (probably) let this be

Section 230 is a federal statute that was duly enacted by Congress. If Trump wanted to change the law, he'd need to convince Congress to pass new legislation, something that's not likely to happen with Democrats controlling the House. Meanwhile, interpreting the statute is up to the courts. Trump gets to fill vacancies, but once a judge is on the bench, they are free to ignore Trump's views on Section 230 or any other law.

But one way agencies can influence the law is through rule-making. When a statute is ambiguous, an agency can issue new rules that clarify the law's exact meaning. Section 230 is in Title 47, the part of the federal code that governs telecommunications law. So in theory, the Federal Communications Commission might have jurisdiction to reinterpret it.

Of the legal scholars we spoke to, Jonathan Adler, a legal scholar at Case Western Reserve University, was the most optimistic about this part of the executive order. "Congress has generally given the FCC fairly broad authority under the Communications Act," Adler told Ars.

But there are a couple of big problems with this plan. The first one is that the FCC doesn't work for Donald Trump. The FCC is an independent commission with three Republican commissioners and two Democrats. Of those five commissioners, only one—Republican Brendan Carr—has shown any interest in following Trump's lead. In a Wednesday appearance on Fox News, Carr described Section 230 as "special bonus protections" for sites like Twitter and suggested that online platforms should lose those protections if they are politically biased.

The other commissioners

But it's not clear if any of the other FCC commissioners—Republican or Democrat—agree with Carr about this. Harold Feld, a legal expert at Public Knowledge, argues that Trump's executive order is "precisely the opposite" of everything FCC Chairman Ajit Pai "has ever said." Pai's entire tenure at the FCC has been focused on minimizing FCC regulation of Internet companies.

CNN's Brian Fung reports that the White House didn't consult the FCC before releasing the executive order. Pai hasn't been shy about ignoring Trump suggestions he doesn't agree with. His response to Trump signing the executive order was pointedly non-committal.

"This debate is an important one," he said. "The Federal Communications Commission will carefully review any petition for rulemaking filed by the Department of Commerce."

Trump's plan is for the Department of Commerce—which does report to Trump—to petition the FCC to reinterpret Section 230. Feld tells Ars that "the petition for the rulemaking process is fairly automatic." A Trump administration request will automatically lead to an FCC docket and an opportunity for members of the public to comment on the proposal.

But experts tell Ars that if commissioners don't want to act on the petition, they have an easy out: they can just ignore it. "Anyone can file any kind of petition for rulemaking," Feld tells Ars. He says that "90 percent of the time" the FCC doesn't do anything in response to a petition. So the FCC could easily just ignore a politically inconvenient request.

The FCC's authority is narrow

Even if Trump can get all three Republican FCC commissioners on board, it's not clear how much authority the FCC has here. Agencies like the FCC don't have the power to rewrite statutes, only to clarify them in cases when they are ambiguous. And agencies tend to get the most deference when they are interpreting statutes they're in charge of enforcing. That doesn't describe Section 230, which is enforced directly by the courts.

The problem for Trump is that Section 230 isn't particularly ambiguous. If someone sues Twitter claiming that a tweet was not taken down "in good faith," it will ultimately be up to the courts, not the FCC, to decide what that phrase means. If the FCC has issued an official interpretation of the phrase, the courts might take that into account. But the courts also might decide that the FCC's opinion simply isn't relevant.

"There's no sense in which Section 230 empowers the FCC," argues Stuart Benjamin, a legal scholar at Duke University. "I don't think any court is going to defer" to the FCC on the best way to interpret Section 230.

Even if the courts do give weight to the FCC's interpretation of Section 230, they'll only do so to the extent that the interpretation is plausible. And Benjamin argues that the clear language of Section 230 (that an online platform won't be liable if it takes down material it considers "objectionable" and does so "in good faith") doesn't provide much room for reinterpretation.

The bottom line is that Trump's strategy here is quite a bank shot. His plan is to ask the Commerce Department to ask the FCC to ask the courts to change how they interpret Section 230. The strategy will fail if either the FCC or the courts refuse to play along.

The feds might be able to redirect ad spending

Under the order, "the head of each executive department and agency shall review its agency's federal spending on advertising and marketing paid to online platforms" and report back to the Office of Management and Budget within 30 days. The Department of Justice will then review the resulting list of platforms and determine whether they impose "viewpoint-based speech restrictions" and are therefore "problematic vehicles for government speech."

Legal scholars told Ars that the Trump administration is on firmer ground here. The First Amendment strictly limits what the federal government can do when it's directly regulating speech. But the government has much broader latitude when it's spending its own money—even if that spending leads to favoring some speech over others.

In a landmark 1991 ruling, for example, the Supreme Court upheld a law banning health care providers at federally funded family planning facilities from talking to their patients about abortion. Doctors had argued that the rule violated their own First Amendment rights. But the high court rejected that argument in a 5-4 decision, holding that the government was entitled to impose restrictions—including speech restrictions—on the use of federal funds.

Benjamin argues that similar analysis would apply if federal agencies blocked ad spending on platforms with policies the Trump administration finds objectionable.

"When the government is speaking on its own, there's basically no concern about viewpoint discrimination," Benjamin said. "The government gets to say, 'Sorry, there are some outlets we don't feel like advertising on.'"

He argued it would be perfectly lawful for the Trump administration to say "we think social media is harming America, so we're going to stop advertising on Facebook."

But Ellen Goodman of Rutgers Law School argued that the issue was more complicated than that. While the government has broad latitude to decide how to spend its own money, she said, spending decisions must be "justified by legitimate governmental interest." If the government is making ad spending decisions because "the president doesn't like platforms that criticize him, that is a viewpoint-based consideration that is pretty far from an accepted government interest," she argued.

So the constitutionality of ad spending rules might ultimately depend on the specifics. If the government can come up with plausible content-neutral criteria for cutting off some platforms, the restrictions could well pass muster with the courts. On the other hand, if there's strong evidence that the government is using ad budgets to punish online platforms for unrelated editorial decisions, that could become grounds for a First Amendment challenge.

Break glass in case of unfairness

The next section of the executive order asks the Federal Trade Commission to use consumer protection laws to police the content policies of major technology companies.

Under existing law, "unfair or deceptive acts or practices" affecting commerce are unlawful, and the FTC has the authority to initiate civil suits against "any person, partnership, or corporation" found to be acting unfairly or deceptively.

The FTC does this all the time—such cases are basically its bread and butter. On Wednesday alone, the agency shared two different press releases about deceptive claims settlements.

The executive order would add user complaints about supposed bias or censorship into the pile of "deceptive claims" over which the FTC has authority. Those complaints would be collected by the White House, which will relaunch its censorship reporting tool.

That tool, first launched in May 2019, purported to collect instances when Facebook, Twitter, and other large platforms suppressed conservative opinions or speech. After about 15,000 responses to the form came in, the president last July gathered together dozens of right-wing political figures, commentators, and activists at the White House to decry platforms' supposed bias.

Data gathered in the relaunched White House tool would this time be reported to both the Justice Department and the FTC—which are then not actually required to do anything about it. The FTC "shall consider taking action," under the terms of the EO, if entities regulated by Section 230 "restrict speech in ways that do not align with those entities' public representations about those practices."

In other words, Facebook or Twitter's rules and community standards would basically become regulated in the same way their privacy policies are. A platform's policy doesn't have to make any specific promises, but whatever it says, the platform needs to abide by it. If it doesn't, that can be considered unfair or deceptive behavior.

Both Facebook and Twitter have posted extensive guidelines that specify what is acceptable on their platforms. Twitter's published rules in particular include exactly the kind of fact-checking scenario about which the president this week has expressed so much rage.

Twitter's notices on Twitter rule:

Labeling a Tweet that may contain disputed or misleading information: If we determine a Tweet contains misleading or disputed information that could lead to harm, we may add a label to the content to provide context. For Tweets containing media determined to have been significantly and deceptively altered or fabricated, we may add a "Manipulated media" label.

And its public-interest exceptions rule:

[I]n rare instances, we may choose to leave up a Tweet from an elected or government official that would otherwise be taken down. Instead we will place it behind a notice providing context about the rule violation that allows people to click through to see the Tweet. Placing a Tweet behind this notice also limits the ability to engage with the Tweet through likes, Retweets, or sharing on Twitter, and makes sure the Tweet isn't algorithmically recommended by Twitter. These actions are meant to limit the Tweet's reach while maintaining the public's ability to view and discuss it.

Ellen Goodman of Rutgers told Ars that the FTC would be on relatively solid ground here from a First Amendment perspective. The companies do post written policies and there is a precedent for the FTC enforcing site policies. "This is core FTC competence," she added. "If it's commercial speech, which is all the FTC has jurisdiction over, then it's much lower First Amendment stakes."

That said, however, Goodman added, "I don't really get how that would have teeth." After all, Facebook and Twitter could just rewrite their policies to give themselves wide discretion in making content decisions.

We've asked the FTC for comment about the executive order and will update if we hear back.

Delegate, delegate, delegate

Just in case the federal agencies might not be enough, as its last parting shot, the order also calls on state attorneys general to get in on the enforcement game—but not necessarily all the state AGs.

The Justice Department and Attorney General Bill Barr "shall establish" a working group to have a look at potential state statutes that regulate unfair and deceptive acts and practices, the order reads. That group "shall invite state attorneys general for discussion and consultation" about pertinent statutes.

In addition to reading over complaints placed through the White House censorship form, the working group would have the task of collecting data about the ways sites "monitor or [create] watchlists of users based on their interactions with content or users" as well as ways platforms monitor users "based on their activity off the platform."

Barr, who appeared with the president at the signing of the statement, appears to be all in. The state attorneys general called up for that working group, however, may be a different matter.

California is a leader among the 50 states in offering privacy protections for Internet users, thanks to the California Consumer Privacy Act. The CCPA was signed into law in 2018 and took effect on January 1 of this year. That law protects users' sensitive personal information, explicitly including data such as browsing history—the kind of on- and off-platform information to which the executive order alludes.

That could make California's attorney general, Xavier Becerra, a natural fit for this kind of working group. But Becerra, as well as other members of California's administration, has also been at the forefront of opposition to a wide array of Trump administration policies proposed or put in place since 2017.

"When it comes to the Internet, smart regulation and innovation can go hand-in-hand," Becerra told Ars by email when asked about the order. "'Smart' does not mean 'petulant,'" he added. "The right to free speech lives on the Internet. But there is no right to lie, defraud or commit crimes on the Internet."