Predicting How Contact Tracing Can Control the Spread of COVID-19

by Emily Henderson, B.Sc.

News-Medical spoke to Dr. Lewis Spurgin about a new study that looked at 'real world' movement data and social contact to understand the spread of COVID-19.

What lead you to research contact tracing and epidemic models?

The Royal Society put together a scheme to bring together researchers from a wide range of disciplines to help with modeling the COVID-19 pandemic.

I volunteered for this scheme and was called up to collaborate with researchers at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

Image Credit: Viacheslav Lopatin/Shutterstock.com

Why was the use of real social network data important to your model?

Human contact patterns are complex and contain lots of hidden structures.

If we simulate social network data we might miss some of this structure, whereas using real social network data captures a lot of this complexity.

How was this data obtained and repurposed?

It was obtained by the BBC and researchers at Cambridge University and the London School as part of a 2018/2019 set of studies.

It is a complex dynamic dataset which records individual locations every 5 minutes over 3 days.

We summarised this data so that we could simulate COVID-19 dynamics over longer time periods.

What factors did you take into account to build your model?

Many things, from the number of starting infections, the reproduction number of the disease, the proportion of cases with symptoms, through to the likely effectiveness of contact tracing and false positive and negative testing rates for COVID-19.

As with all models there are a lot of assumptions we have to make, but we try to base these on real-world data wherever we have evidence to do so.

What did your epidemic model and study results show?

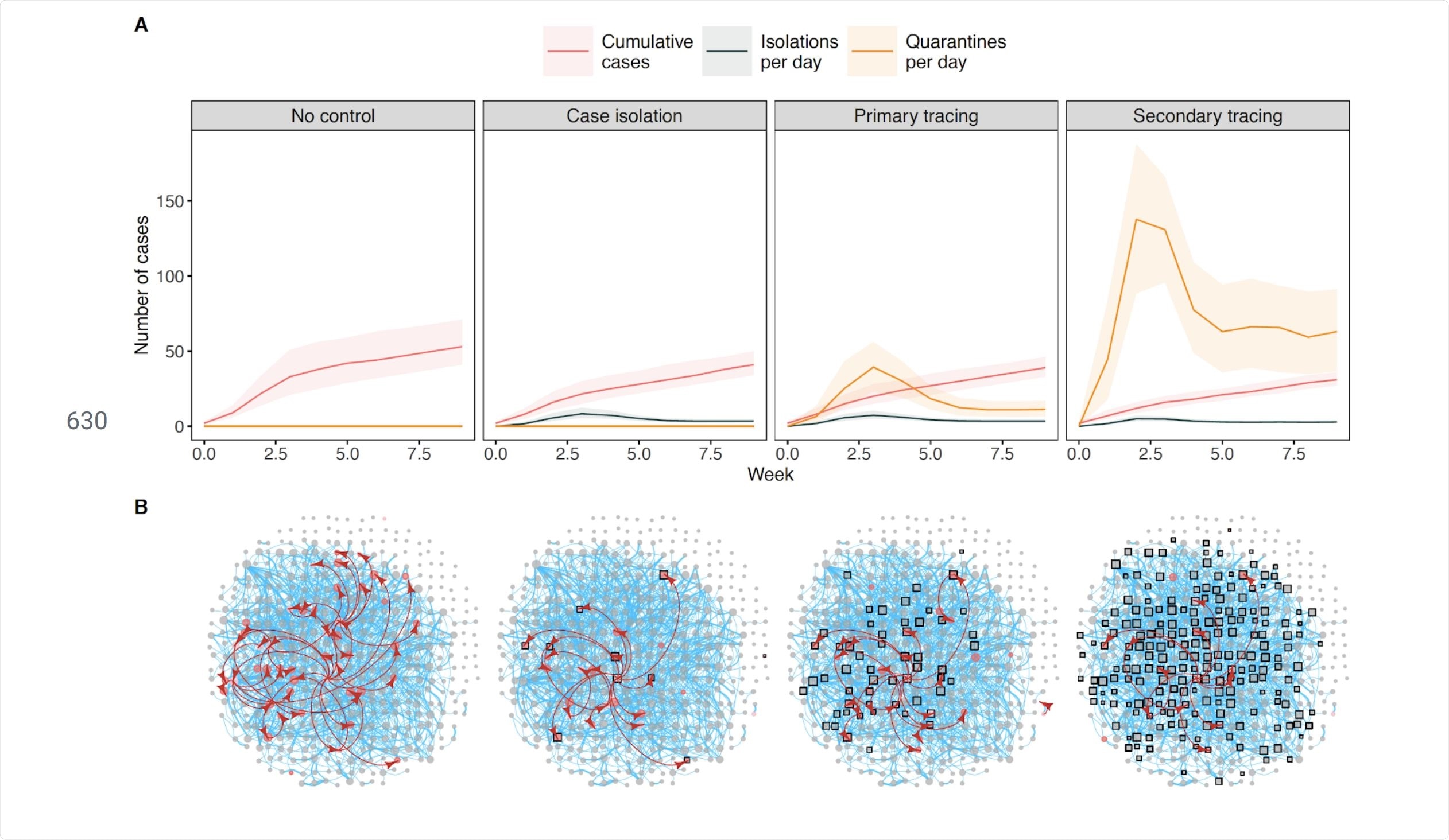

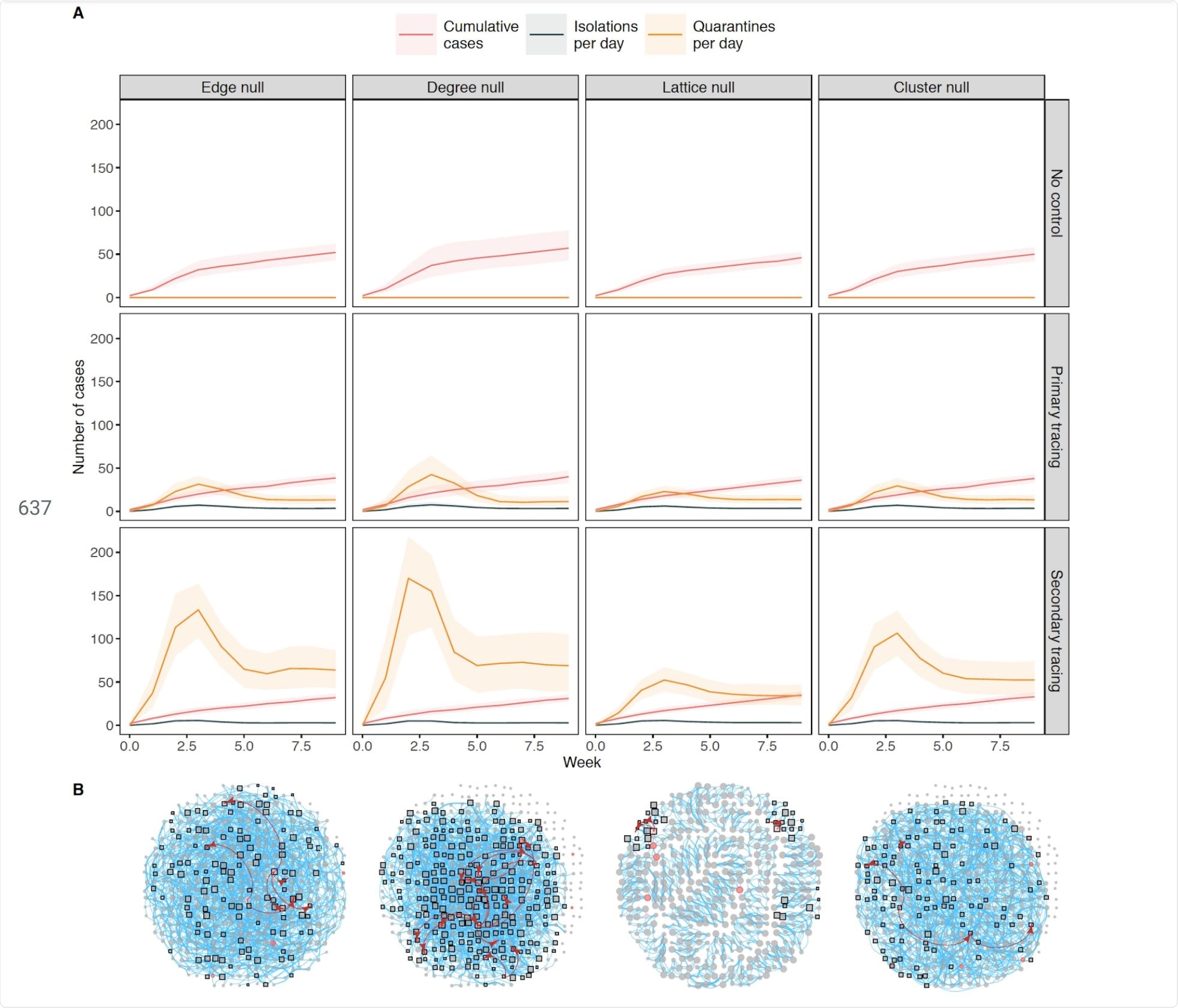

It shows that tracing and quarantining of contacts can reduce outbreak size by up to 50% in our network, but also that this can involve quarantining a very large number of people.

If we combine contact tracing with testing and/or physical distancing, the model suggests that outbreak control can be achieved without quarantining quite so many people.

What does your model suggest is the best strategy or combination of strategies to prevent infection and outbreak whilst allowing societies to start up again?

It suggests that combining multiple strategies may be necessary for the medium-longer term.

What are the limitations of this study and how can improvements be made to adapt it to widerscale society?

Our study uses data from one small town in England. We do not yet know to what extent this will apply to other social contexts.

While the Haslemere network is one of the best publicly available datasets on human contact patterns, it is incomplete.

Only a fraction of the town’s population took part in the original study, so we have to view our results in light of that.

Could this model, or more developed versions, be used to ease lockdown regulations without risk of another outbreak?

No, not on its own.

It can, however, be used as part of a much wider process that combines a broad range of scientific disciplines with political decision making.

Could the theory behind this model be applied on an international scale to help eliminate the pandemic?

The model can be adapted to be used over other networks, as and when they are available. And models such as ours can form an important part of a broad evidence base on how to implement policy decisions.

But this model, or indeed any model, will not eliminate the pandemic. This, in my opinion, is primarily a political problem.

Do you think research like this needs to continue even when COVID-19 has been managed in order to better prepare for future pandemics?

Yes, any research that helps us prepare for future pandemics is undoubtedly a good thing.

What are the next steps for your research?

We would like to look at outbreak dynamics across a range of networks and settings, including schools and workplaces.

Ideally, we would like to be able to directly compare outbreak dynamics across different settings in order to inform policy, but this will depend on the quality and availability of network data.

Where can readers find more information?

About Dr. Lewis Spurgin

I am an ecologist based at the University of East Anglia, who mainly works on organisms that are not human.

I use a combination of field studies, lab experiments and mathematical models to understand the how and why populations vary over time.

This COVID-19 work has come about via the Royal Society’s Rapid Assistance in Modelling the Pandemic (RAMP) scheme.