The Indian Express

Najibullah has a visitor — why did a top Afghan official go to the grave of a long dead, much reviled President?

In 1996, the Taliban shot Najibullah and strung his body up on an electricity pole. To recall him now is to recall the extreme violence of the Taliban. It is also a finger in the eye of Pakistan.

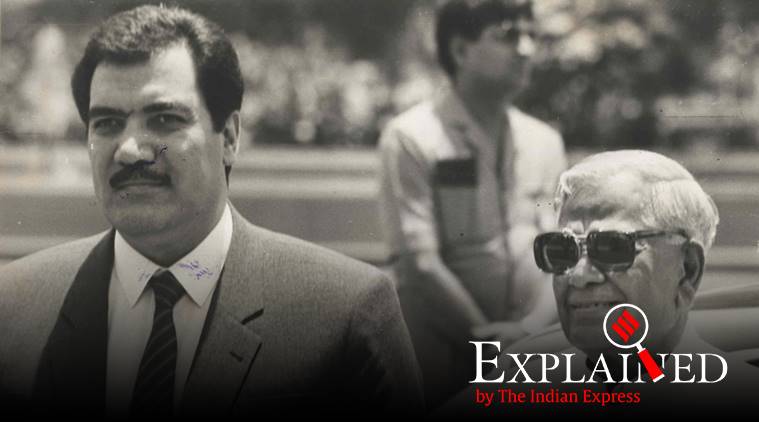

by Nirupama SubramanianOver the Eid holidays in Afghanistan, the grave of Mohammed Najibullah, the country’s President from 1987-1992, received a surprise visitor. Hamdullah Mohib, the Afghan National Security Adviser, paid a quiet visit to the Melan graveyard in Gardez, in the eastern province of Paktia, where Najibullah was buried after his barbaric killing by the Taliban in 1996.

This was the first time that a senior member of any post-Taliban Afghan government has visited the grave of an Afghan political leader whose association with the Soviet invasion made him a controversial and polarising figure, but who in his final years transitioned to an Afghan nationalist and believed — wrongly, as it turned out — that his Pashtun roots could save him from those who wanted him dead.

In Afghanistan’s book of tragedies, his gruesome end at the hands of the Taliban is right at the top, the macabre opening scene of five years of Taliban rule over the country.

“During Eid, I visited the tombs of two historical figures in our country, with whom my family had differing views in the past. However, bringing real peace depends on tolerance, tolerance, and overcoming predetermined classifications,” Mohib tweeted on Wednesday, a day after photographs of him offering prayers at Najibullah’s grave site were posted by Afghans on social media.

The other grave that Mohib visited was likely that of Ahmad Shah Massoud, the leader of the Northern Alliance, who was killed by al-Qaeda hours before the 9/11 attacks. He is buried in his home province of Panjshir Valley north of Kabul.

Mohib said in a second tweet: “Today’s Afghanistan is made up of different beliefs that used to be antagonistic to each other, but today all work under one system, one flag and one Afghanistan.”

The prevailing context in Afghanistan

Was Mohib’s decision to embrace the past his alone, or did it have the backing of the government?

There is no telling. But in his words, and particularly in his visit to Najibullah’s grave, there seemed a message for multiple audiences — for the Taliban, whose February agreement with the US on the withdrawal of American troops from Afghanistan, has thrown the country into another cycle of violent uncertainty; for Pakistan, which believes it is at the cusp of proxy rule over Afghanistan; and for Afghans themselves.

The unexpected throwback to Najibullah came during a three-day Eid ceasefire declared by the Taliban. The Taliban had declared a similar ceasefire in 2018, but that did not last beyond the holidays. Afghans, who welcomed the break in the relentless bloodletting of the previous weeks, are praying it will be different this time.

On May 26, the third and last of the ceasefire, the Afghan government released hundreds of Taliban prisoners, ending an impasse in the implementation of the US-Taliban deal, and perhaps paving the way for the next stage, which is for talks between the Taliban and other Afghan representatives, known as “intra-Afghan talks”.

The prisoner release appeared to have helped the ceasefire hold, as of now at least for two more days. The Afghan government has expressed the hope that the undeclared truce will continue, so that it can be built upon.

“The détente that started during Eid ul-Fitr continues despite reports of scattered incidents to the contrary. A ceasefire is a complex operational undertaking that requires significant and ongoing coordination to avoid incidents. Those efforts will continue,” said National Security Council spokesman Javaid Faisal on Twitter on Friday morning.

Where does Najibullah come into all this?

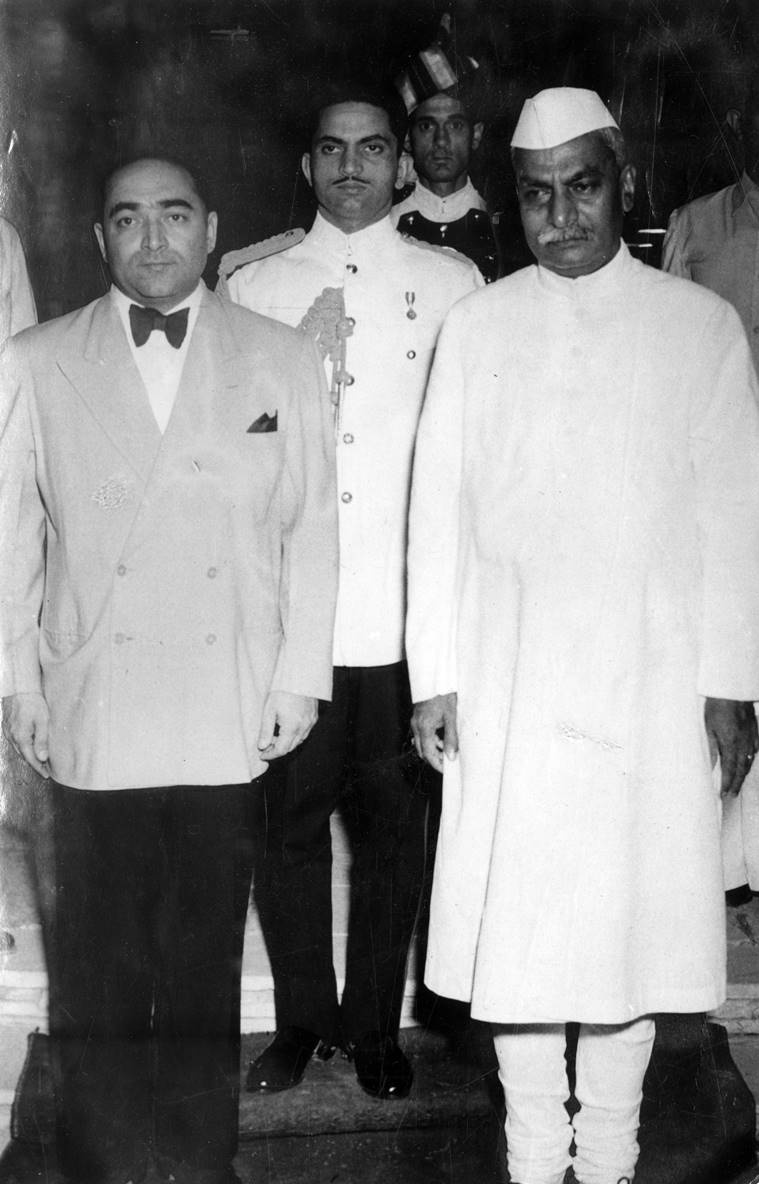

A Pashtun who began his political career while he was a medical student in Kabul University, Najibullah started out as a member of the communist People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan. The PDPA seized power in the 1978 Saur revolution, but it was only with the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979 that Najibullah’s rise began.

He was first the security boss of Afghanistan as the head of KHAD, the Afghan secret service that was for all purposes run by the KGB. Over the course of the next 14 years, Najibullah would travel the political spectrum from Marxist to Afghan nationalist.

From 1987, when Moscow installed him as President, Najibullah initiated steps for a return to peace, known as the National Reconciliation Policy (NRP). Glasnost was sweeping through the Soviet Union, and the Red Army’s continued presence in Afghanistan looked untenable. Najibullah realised it would not be long before he would be on his own.

Under the NRP, Najib reverted to the country’s old pre-communist name of Republic of Afghanistan (from 1978 to 1987 it was known as the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan), Islam was declared the state religion, and the PDPA itself became the Hezb-e-Watan Party, in a bid to appeal to the Islamist mujahideen victors of the war.

But his efforts were in vain.

As the mujahideen began taking over Kabul in 1992, he resigned. India tried to evacuate him from Afghanistan that April in an operation that went wrong badly. The car in which he was being taken to the airport (by some accounts, the Indian ambassador’s car) was stopped outside the airport gates by guards owing allegiance to Abdul Rashid Dostum, a warlord who had been bankrolled by Najibullah, but who had switched sides when the payments stopped, after the Afghan government’s tap went dry following the break-up of the Soviet Union in 1991.

The plane that was to fly Najibullah to Delhi was waiting on the runway, with the United Nations envoy to Kabul sitting inside. Najibullah had a heated argument with the guards, but failed to get them to let him pass. Nor could he go back to the President’s palace. So the car took him to the UN compound where he would live for the next four and a half years in self-imprisonment.

The Taliban took over Afghanistan from the warring factions of the mujahideen after a four-year long civil war. In 1996, they captured Kabul from Ahmad Shah Massoud’s retreating forces. Najibullah, his brother and two other companions, who had been sheltering in the UN compound, were left to fend for themselves.

Massoud did offer to give him safe passage to the north, but he turned down the offer, as he was still counting on his Pashtun ethnicity to make a deal with the Taliban, which he believed would be more complicated if he escaped with a Tajik to the north.

With no UN officials left in the compound, a small team of the Taliban, including, according to some accounts, an ISI officer in disguise, stormed in. Najibullah and his brother were beaten, dragged behind a jeep, castrated, shot, and then strung up from a traffic light pole outside the Presidential palace.

It was a chilling message to the people of Kabul and Afghanistan. The violence shocked the world, and was condemned as un-Islamic by even Saudi Arabia, a friend of the Taliban.

Significance of Mohib’s visit to Najib’s grave

Large sections in Afghanistan have been against the US-Taliban deal, describing it as a handover of the country to the Taliban once again.

Mohib, blackballed by the US ever since his remarks against US Special Envoy to Afghanistan Zalmay Khalilzad, is part of the country’s security apparatus, which has no love lost for Pakistan’s ISI, and sees the Taliban as a proxy of Pakistan.

At such a time, the show of posthumous solidarity with Najibullah, especially after a month of extreme violence in Afghanistan, has served to remind of Najibullah’s own efforts at an Afghan-led and Afghan-owned national reconciliation, and how that failed. It recalls the extreme cruelty of the Taliban as they established themselves as the rulers of Afghanistan.

It is also a finger in the eye of Pakistan.

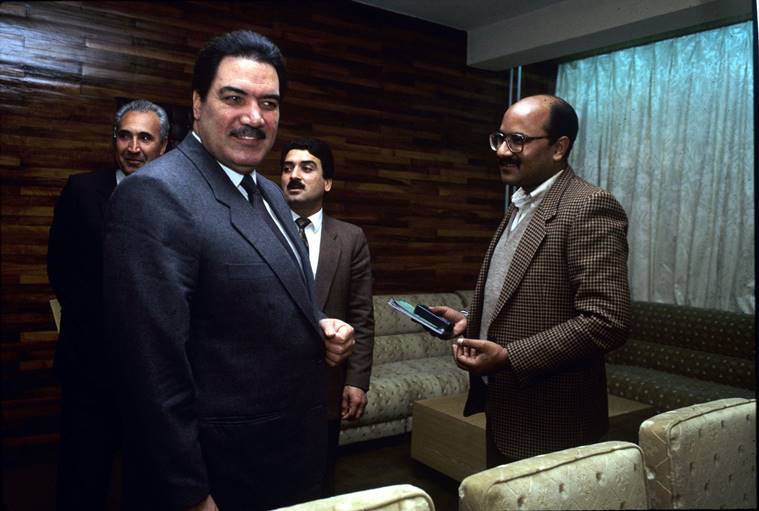

Najibullah, after all, was the leader who managed to thwart the powerful ISI and its boss Hamid Gul’s dream project of toppling his government and installing a mujahideen regime in Kabul just a month after the Soviet forces withdrew in February 1989.

Gul had planned that the mujahideen would carry out a full military-style assault on Jalalabad, the Afghan city closest to the Khyber Pass, and declare it as the seat of the new government. Gul calculated on the Afghan army’s capitulation minus Soviet help.

But after a brief advance, just the opposite happened.

The Afghan army managed to inflict a huge defeat on the mujahideen and its backers, with the help of its An-32s and Scud missiles. The Soviet Union backed Najibullah with material help during this time. The battle lasted five months. Over 3,000 mujahideen were killed, many thousands of civilians were either killed or had to flee.

Benazir Bhutto, who had then just been elected for the first time, fired Gul. The episode set the the stage for the next few seasons of civilian-military tensions in Pakistan.

More significantly for the present times, as the Pakistani political commentator Mohammed Taqi wrote in a 2014 essay, Najibullah “was immensely popular among the Pashtun nationalist rank and file in Pakistan”, although the leadership of two big Pashtun parties — the Awami National Party and the Pakhtunkwa Milli Awami Party — did not stand by him when he needed them. Taqi described Najibullah as the “Afghan Prometheus”.

With Pakistan doing everything to suppress a new wave of Pashtun nationalism through the Pashtun Tahaffuz Movement in its own north-west, the last thing it would wish to see is the resurrection of a long dead Afghan leader as a Pashtun hero.

Taqi told The Indian Express that while in Afghanistan Najibullah was disliked by most people because of his “brutal past”, there has also been a realisation of what he had tried to pull off.

“Many do see him as someone who really tried truth and reconciliation” through his National Reconciliation Policy. In that sense, said Taqi, Mohib’s visit to Najibullah’s grave, besides being “anti-Taliban messaging”, was “also a truth and reconciliation gesture to Afghans themselves”.

It is ironic that the effort to acknowledge Najibullah as an Afghan nationalist has come at a time when India is considering opening channels to the Taliban, with which it has never had formal relations. While Najibullah’s family escaped to India months before he was deposed in 1992, and has lived in Delhi ever since, the Narasimha Rao government accorded formal recognition to the ISI-CIA backed mujahideen government of Gulbuddin Hekmatyer in Kabul, willing to put aside animosities with Pakistan for pragmatic compulsions.

The wheel has turned full circle. As Delhi considers if talking to the Taliban is better than being left out of the table altogether, Najibullah’s daughter, Muska Najibullah, captured some of the irony in a tweet on May 15: “#TheKhalilzadStrategy – how to distract the world from a failed #peace #deal in Afghanistan? Drag one of its oldest and loyal friends and create a regional mess”.