100,000 dead in the US

‘We had to overcome fear’: the unsung heroes caring for Americans as deaths pass 100,000

Doctors, nurses and millions of others are helping during the pandemic – by delivering food, making masks, and working at homeless shelters, in palliative care and at nursing homes

by Jessica Glenza, Ankita RaoThere are many words for the workers who have borne the brunt of the Covid-19 pandemic: frontliners, essential workers, in some cases, heroes.

Doctors and nurses in the intensive care units and first responders, who are fundamental to the survival of our communities, have become the face of the emergency response.

But as the death toll in the country reaches 100,000 people in the US, millions of others continue to care for Americans during the worst global pandemic in more than a century. Here are five of their stories.

‘Who else was going to feed them?’

Jeff Allison, has been working seven days a week. He spends six hours a day packing boxes and boxes and boxes of food for the residents of Birmingham, Alabama, left hungry by the devastating economic impacts of Covid-19 lockdowns.

In the early stages of the pandemic, Liberty church, where Allison is also a youth pastor, partnered with Grace Klein Community, a faith-based food bank in Hoover, Alabama.

Together, the groups were able to form a drive-through food distribution center in Birmingham, whose boxes have now expanded to provide people with milk, sweet iced tea, salad greens, infant formula and diapers. Each afternoon, the group hands out between 120 and 140 boxes.

They estimate that Allison, alongside a group of about a dozen teenagers and a few adults, have fed more than 5,000 families over the last eight weeks.

“We had to overcome fear,” said Allison. “Who else was going to feed them? There was no other feeding program happening in Birmingham.”

At least 36 million Americans have filed for unemployment benefits in the last two months. Alabama provides some of the lowest such benefits in the country, at just $275 per week for 14 weeks. By comparison, nearby Georgia pays workers $365 per week for 12 weeks. (Congress provided another $600 per week for unemployed people, including gig workers.)

While Alabama’s economy is reopening faster than other hard-hit locations, such as New York City, Allison estimates people will continue to rely on food banks for weeks as they wait for paychecks and catch up on bills, all putting pressure on food budgets.

“We’re all pitching in, and with God’s help anything can be done,” said Allison. Jessica Glenza

‘The struggle for N95s was devastating’

In March, as the extent of community transmission of Covid-19 in New York City became apparent, shortages of personal protective equipment such as masks and gowns were dire, leaving healthcare workers vulnerable to infection.

Dr Natasha Anandaraja, who oversees a wellness and resiliency program at a major Manhattan hospital, saw the stress this caused health workers acutely. So she founded an organization called Covid Courage to give face shields, masks and gloves directly to health workers across New York City.

“I expected by this point that, [the] immediate need had passed, but I think we’re just digging down into layers of need,” said Anandaraja. “We’re still coming across healthcare workers in the smaller hospitals who have been using the same N95 for two weeks.”

Since the beginning of the pandemic, the group has raised nearly $88,000 with the help of Georgia-based charity School of Humanity and Awareness, which extended the group non-profit status.

“The struggle for N95s was devastating, it was not adequately handled, it caused incredible stress and high rates of illness,” said Anandaraja.

Covid Courage has enlisted 3D printing companies to manufacture face masks, found new suppliers for N95 masks, and coordinated with sewing groups to make cloth face masks, and volunteers to pass them out to the public on the subway.

Now, she is working with the New York City public advocate’s office on a pilot program to deliver reusable masks.

“Relying on disposable PPE is not sustainable, so we have come across a few pockets of doctors across the city who started using reusable respirators,” she said.

“We’re not a huge organization, but we’re trying to do a huge amount of advocacy,” Anandaraja said. Jessica Glenza

‘Everything that was a stressor, it’s that times 20 now’

Catita Perron was dealing with crises every day, even before the pandemic hit.

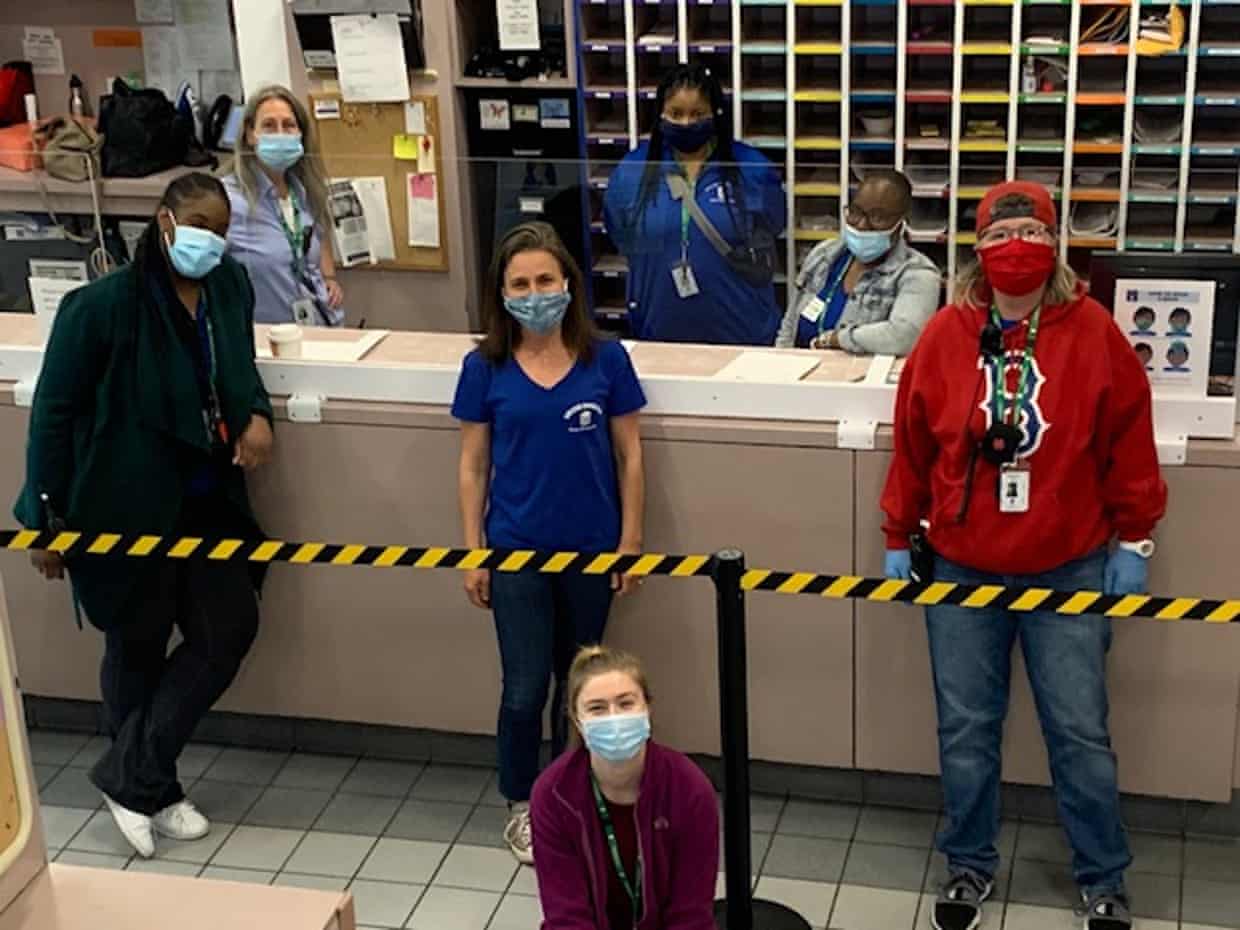

As the director of the Pine Street Inn women’s homeless shelter in Boston, she and her staff regularly deal with mental health issues, trauma and poverty, sometimes working long days or sleeping overnight in their offices during a blizzard.

But the pandemic made everything exponentially more difficult. “For our guests who are struggling, everything that was a stressor, it’s that times 20 now,” she said.

In late March, Perron and her team sprang into action. They worked with Boston’s homeless shelter network to spread people out across more buildings, put shower curtains up between beds, and doled out masks, gloves and face shields.

Through Boston’s Health Care for the Homeless, a non-profit group, they tested as many people as possible, attempting to stave off outbreaks among a highly vulnerable population. One out of three homeless people in the city were testing positive for Covid-19 in April, according to city officials.

That kind of work, Perron said, made exposure unavoidable. “I thought: there’s no way I’m not going to get this.”

Her prophecy became true in early April. Like many frontline workers, she made the difficult decision to move out of her home, where she lived with her two young children and husband. She wouldn’t return for five weeks.

“Honestly, that was the hardest part for me,” she said.

Last week, Perron was finally able to go home and work toward a new equilibrium. Meanwhile, she said, the situation in Boston and at the shelter was slowly becoming more manageable.

There’s still a long road ahead, she said. With the economic downturn, she’s worried there will be more homeless people than usual, and at a time when the shelters are hoping to keep their numbers lower to prevent outbreaks. And, amid the city lockdown, it has been hard to process housing applications.

“My staff, they work for not that much money, they work long hours,” she said. “You know you’re essential when you take the job.” Ankita Rao

‘We don’t go into a situation thinking we’re going to cure anybody’

Dr Jane deLima Thomas’ role as a doctor is focused on healing, but it’s not always about treatment.

“We don’t go into a situation thinking we’re going to cure anybody,” she said from Boston, where she leads teams at Brigham and Women’s hospital and the Dana Farber Cancer Institute.

Palliative care physicians are tasked with making patient’s lives better in the moment, even if they’re not likely to recover. This can mean managing pain, coordinating with family members to honor a patient’s wishes, or involving a chaplain for spiritual support.

During the Covid-19 pandemic, which had claimed 577 lives in Boston by Sunday, this took on even more intensity.

Her team’s patient panel, usually about 20 or 30 people per day, spiked into the 80s. Hospitals didn’t allow family visits, making phone calls about end of life decisions more difficult, especially when there were language barriers.

The tools deLima Thomas relies on were also strained. “Presence, touch, compassion,” she said. “That’s harder to do over video or on the phone. Even the basics, like sitting at a patient’s bedside and holding their hand, we don’t have access.”

deLima Thomas recalled having to tell a fellow health worker that they couldn’t visit their dying parent, or listening to the weeping children of a couple who were both on ventilators in the Intensive Care Unit. “That much uncertainty, and that much fear, and that much distance,” she said. “It heightened the emotional intensity.”

Then suddenly, amid the chaos at the hospital, deLima Thomas’ own father died.

“That might’ve been the hardest thing – that I couldn’t be as helpful as a palliative care doctor to my mother.” Ankita Rao

‘We’re holding their hands, because no one wants to die alone’

Chris Brady is a nursing home aide in Glens Falls nursing and rehabilitation center in upstate New York, where there has been a large outbreak in long-term care homes. With families largely barred from the facilities, Brady and his colleagues have tried to be a source of comfort for residents.

“I feel like some of the articles I’ve been reading are missing the love and compassion of the aides and the nurses,” he said. “They don’t say that when the family won’t come into the building to say goodbye, we’re there. We’re holding their hands, because no one wants to die alone.”

In more than a dozen states, nursing home deaths account for more than half of all Covid-19 deaths. Patients are scared, nursing homes are being scrutinized like never before, and in the midst of this some of the lowest-paid members of the healthcare workforce – nursing home aides – have become the frontline of comfort and care for America’s elderly.

Brady has worked with Covid-19 patients in the nursing home since the beginning of the pandemic, roughly two months ago. More than two dozen residents he cared for have died. “A lot of our staff leaves crying,” he said.

At the same time, he has been unable to see his family because of his work. He is also attending school (virtually) and is about to graduate with a licensed practical nurse certification – the next step in his goal to become a registered nurse.

“Life’s short,” he said he has learned. “Don’t forget to say, ‘I love you,’ before you leave your loved ones.” Jessica Glenza