China’s Kashmir Move: The Great Geopolitical Puzzle of South Asian Chessboard

by Mir Sajad“We will not attack unless we are attacked. But if we are attacked, we will certainly counter-attack”. –Cited by Chinese Foreign Ministry(2020) .Mao Zedong

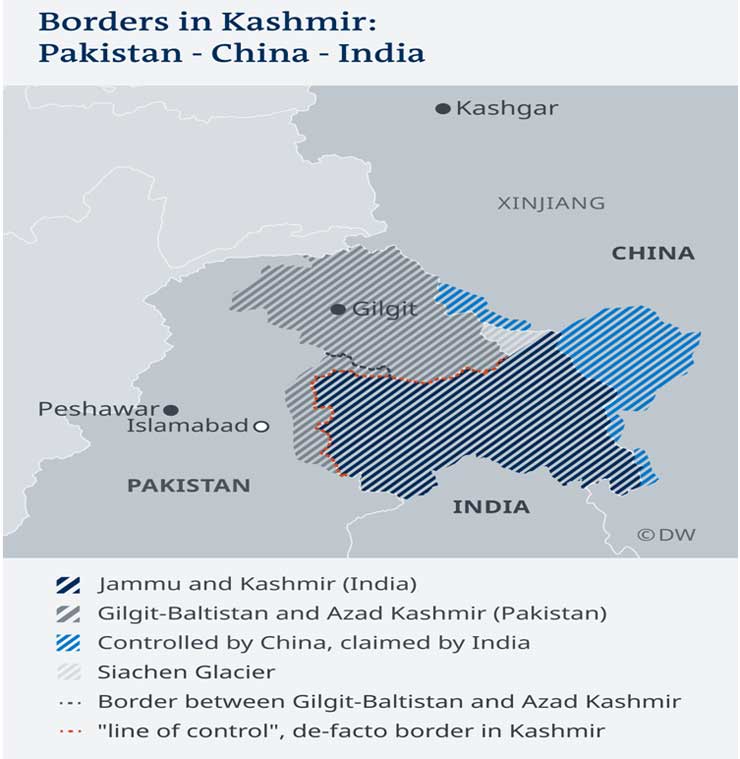

After scraping of Article 370 in August previous year China has emboldened its stand on raising the Kashmir issue twice in United Nations joining many international countries in the unprecedented criticism on India’s action in Kashmir. Before August, the last time that Kashmir Issue got resonated at the UNSC forum was in 1971 and has been flagged twice since then within a span of five months. China was the main actor in highlighting the ‘disputed’ nature of Kashmir’s historical and political entanglements. This powerful spectrum of internationalising the hostilities and tragedies being carried out in Kashmir cannot be brushed away. This has weakened the rhetoric of ‘bilateral issue’ between India and Pakistan. After the 2017, Indian and Chinese troops had a face off in a 74-day standoff in Doklam on the Sikkim border During the recent track of intense border skirmishes and rush of troops by China around Pangong Tso Lake in Galwan Valley shifted the focus of international attention from hollow diplomatic slogan of ‘bilateral issue’ to potential regional interventions in the arbitration on account of excesses and human rights violations being perpetrated in this ‘conflict torn state’. There is an absolute clampdown on political activities of the state and is governed directly by the central government with Lieutenant Governor overseeing the region. The basic democratic right of exercising the political freedom too has been robbed off as more than half of political leaders are under the house arrest.”China is always opposed to India’s inclusion of the Chinese territory in the western sector of the China-India boundary into its administrative jurisdiction,” reiterated the Chinese foreign ministry spokeswoman, Hua Chunying, following India’s Kashmir move.”Recently India has continued to undermine China’s territorial sovereignty by unilaterally changing its domestic law,” Hua added. “India’s action is unacceptable and would not have any legal effect” in the wake of giving UT status to Ladakh. The test flight of the unmanned helicopter AR500C designed for high-altitude operation flared up at a period when China-India border tensions have been intensified bolstering border vigil measures and made some moves in response to construction of recent, illegal defense facilities into Chinese territory in the Galwan Valley region. China has built a stranglehold on a large part of the Galwan valley which includes a portion of Ladakh region from the past 10 days by entering up to the 3-4 Km’s of Indian land making it China’s first attempt since the sixties, to make alterations on this part of the Line of Actual Control. As per estimates China is making arrangements for making inroads inside Indian territory in asserting its claimof the entire Galwan valley including a portion of Ladakh. The Galwan river flowing from the contested Aksai Chin region, claimed by India, to Xinjian region in China before entering Ladakh. WHO recently showed parts of Ladakh as part of China on its map with color codes and dotted lines with showing earlier parts of Arunachal Pradesh part of it in Sky Map’s, Chinese authority on maps .Satellite imagery from Shadow Break Intl. has shown a close-up view of airport with a possible line-up of four fighter jets either J-11 or J-16 fighters of the Chinese PLA Air Force and massive constructions being carried out at a high altitude Chinese air base, located just 200 kilometres away from the Pangong Lake

China’s Kashmir Connection

Chinese diplomatic behaviour has been swinging in dribs and drabs but it swayed drastically in after 1963 agreement, with China exhibiting more pro- Paksitan and stated in 1964 “The people of Kashmir should beallowed a UN supervised plebiscite in Kashmir” ( John W Garver, “Evolution of India’s China Policy” in Sumit Ganguly (Ed), India’s Foreign Policy: Retrospect and Prospect, New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2010).After second India-Pakistan war in 1965,China recognising the gravity of the situation after couple of weeks of the war, China’s official mouthpiece the People’s Daily’s while describing the situation in the Indian state (then) of J&K as a “popular struggle” and “armed uprising” attributing it to the Indian government’s bigoted governance (Mao Siwei, “China and the Kashmir Issue”, Strategic Analysis, March 1995. A new dimension of China’s Kashmir policy has been the issuance of loose-leaf/stapled visas to Kashmiris considering entire J&K as disputed (Jayadeva Ranade, “The Age of Region: China seems to Review its Asia Strategy”, The Times of India, New Delhi, 13 January 2010) Furthermore, in July 2010 China denied a visa to Indian Army General BS Jasawal (Indian Army General) on the grounds of his posting in a territory that was “ , head of the sensitive Northern Command based in J&K. Clarifying the denial, Beijing stated that it would not be possible to give Jasawal a visa because of his posting in the territory that was “difficult” (“Now Three Chinese Army Officers refused Visas”, The Hindustan Times, New Delhi, 28 August 2010).There seems an intersection of interests in China-Pakistan relations with China investing heavily in Pakistan and seemingly ‘all-weather’ friendship bond between the two with Kashmir hyphenating perfectly on this mutual regional integration. In the Rambo-styled film ‘Wolf Warrior 2’ in 2017 China exhorted the geo-strategic message through this film by flashing the Han dynasty saying, as:“Whoever offends China will be punished, no matter how far they are”. Chinese have been exhuming the ghosts of ‘silk route’ by announcing to the world the ‘new silk route’ (The Return of Marco Polo’s World; War, Strategy and American Interests in the Twenty-First Century by Robert D. Kaplan, 2018) and Kashmir remain the core of that grand project.

China’s Geo-Strategic Might and Xi Jinping’s ‘New Era’

The strengthening of ‘comprehensive national power’ has gained centrality for China’s geo-strategic interests for evaluating and measuring national standing with respect to other nations. There are enough reasons to believe that China would remain engaged with the process of re-structuring its ‘comprehensive national power’ (Annual Report on the Military Power of the People’s Republic of China) in the coming years, and hence would pursue the principle of cooperation with other countries while avoiding a direct conflict. China’s stress has been essentially, the antithesis of the shoot-from-the-hip diplomacy that appears to be the strategy ‘du jour’ around the world. Fluctuating between romanticism, underlined by stretches of rhetoric on commonality, and an intense wariness of each other’s intentions, Sino-Indian relations have inclined to spurn easy predictions on either their drifting apart or drawing close. This idea of geo-strategic planning is part of the splendid Chinese traditional thought and is also the bridge between the diplomatic thought and policy-making thought. China’s global strategy has gone over the stages of “the two camps”, “the three worlds”, “the four layouts” and “the five equal considerations” which illustrates China’s tactical design in always keeping up with the times. China’s regional strategy has developed from “developing friendly relations with its neighbouring countries” to “establishing proper orders of the local region and achieving mutual benefits and win–win results with countries of other regions”. The main kernel of playing up Chinese-ness is to play it down as both are having strong dialectal relations. There is a traditional Chinese poem, which corroborates the same reading as, “beautiful as she is, she just tells spring is coming, never intending to steal any show; when all flowers are in blossom, she smiles happy therein”. The epistemic connexions of ‘power’ and “undiluted’ sovereignty have the similar configuration in their foreign policy dynamics but New Delhi’s approach to South Asia will always be different form Beijing . There is a fascinating pattern of intriguing, unpredictable and dramatic unfolding of geo-political interest being wrestle in the volatile rings of Himalayas reincarnating Connolly’s ‘Great Game’ spectacle once again which will determine the course of South Asian geopolitical climates in the Xi Jinping’s “new era” geopolitics