The Indian Express

Locust attack: How they arrived, seriousness of the problem, and ways to solve it

Over the last few days, swarms of desert locust have reached urban areas of Rajasthan, and parts of MP and Maharashtra. A look at how they arrived, the seriousness of the problem, and ways to solve it

by Parthasarathi BiswasWhat are ‘desert locusts’ doing in non-desert lands?

Desert locusts (Schistocerca gregaria), which belong to the family of grasshoppers, normally live and breed in semi-arid or desert regions. For laying eggs, they require bare ground, which is rarely found in areas with dense vegetation. So, they can breed in Rajasthan but not in the Indo-Gangetic plains or Godavari and Cauvery delta.

But green vegetation is required for hopper development. Hopper is the stage between the nymph that is hatched from the eggs, and the winged adult moth. Such cover isn’t widespread enough in the deserts to allow growth of large populations of locusts.

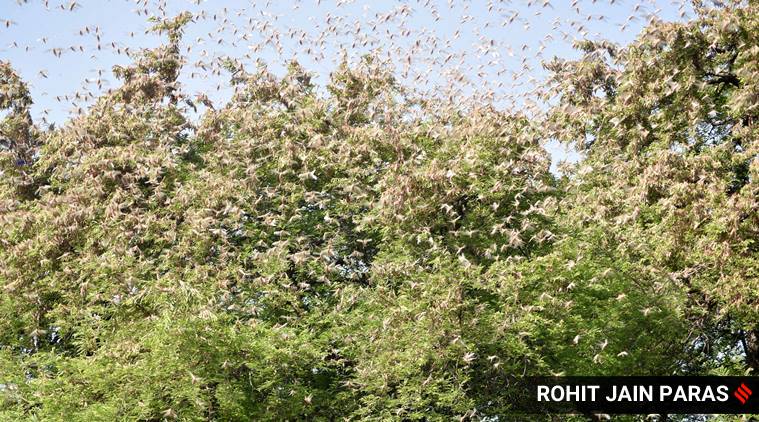

As individuals, or in small isolated groups, locusts are not very dangerous. But when they grow into large populations their behaviour changes, they transform from ‘solitary phase’ into ‘gregarious phase’, and start forming ‘swarms’. A single swarm can contain 40 to 80 million adults in one square km, and these can travel up to 150 km a day.

Large-scale breeding happens only when conditions turn very favourable in their natural habitat, desert or semi-arid regions. Good rains can sometimes generate just enough green vegetation that is conducive to egg-laying as well as hopper development.

This is what seems to have happened this year. These locusts usually breed in the dry areas around Ethiopia, Somalia, Eritrea along the eastern coast of Africa, a region known as the Horn of Africa. Other breeding grounds are the adjoining Asian regions in Yemen, Oman, southern Iran, and in Pakistan’s Balochistan and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa provinces. Many of these areas received unusually good rains in March and April, and that resulted in large-scale breeding and hopper development. These locusts started arriving in Rajasthan around the first fortnight of April, much ahead of the normal July-October normal.

The Locust Warning Organisation, a unit under the Agriculture Ministry, had spotted these and warned of their presence at Jaisalmer and Suratgarh in Rajasthan, and Fazilka in Punjab near the India-Pakistan border. Subsequently, there has been arrival of several swarms from the breeding areas.

When July-October is the normal time, how did they arrive so early?

The answer to this question probably lies in the unusual cyclonic storms of 2018 in the Arabian Sea. Cyclonic storms Mekunu and Luban had struck Oman and Yemen respectively that year. Heavy rains had transformed uninhabited desert tracts into large lake where the locust swarms breed. If left uncontrolled, a single swarm can increase 20 times of its original population in the first generation itself, and then multiply exponentially in subsequent generations.

Scientists of LWO had got the first whiff of impending problem in the 2019-20 rabi season when unusually active swarms were reported in Rajasthan, Gujarat and some parts of Punjab. Control measures minimised damage in India during that time. But further action could not be taken because of the lockdown around the world, and the swarms remained active in Yemen, Oman, Sindh and Balochistan areas. The present swarms are their direct descendants, and are arriving in India in search of food.

But why the further eastward movement?

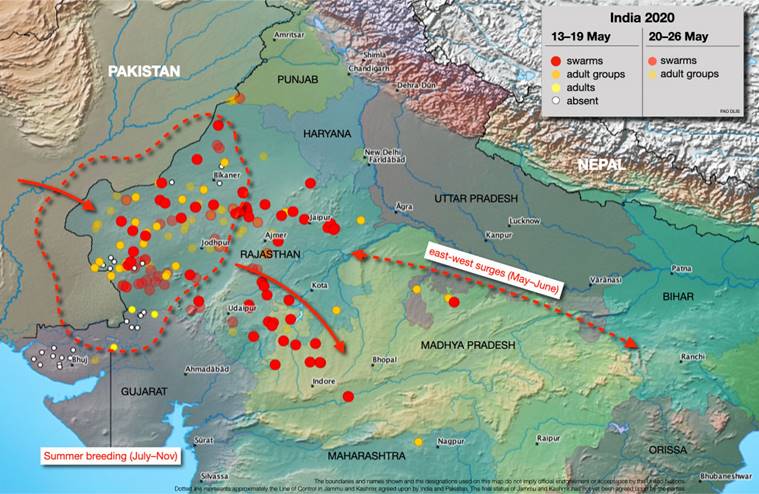

The current swarms contain “immature locusts”. These feed voraciously on vegetation. They consume roughly their own weight in fresh food every day, before they become ready for mating. But right now Rajasthan does not offer enough to satisfy their hunger. With no crops in the field, they have been invading green spaces, including parks, in Jaipur and orange orchards near Nagpur. LWO estimates that at present there are three or four active swarms in Rajasthan while Madhya Pradesh has two to three of them. A small group deviated into Maharashtra as well.

Once they start breeding, the swarm movement will cease or slow. Also, the breeding will happen mainly in Rajasthan.

Apart from the search for food, their movement has been aided by westerly winds that were, this time, further strengthened by the low pressure area created by Cyclone Amphan in the Bay of Bengal. Locusts are known to be passive flyers, and generally follow the wind. But they do not take off in very strong windy conditions.

So, what damage have they caused?

So far, not much, since the rabi crop has already been harvested, and farmers are yet to really start kharif sowings. The UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) has, however, predicted “several successive waves of invasions until July in Rajasthan with eastward surges across northern India right up to Bihar and Odisha”. But after July, there would be westward movements of the swarms that will return to Rajasthan on the back of changing winds associated with the southwest monsoon.

The danger is when they start breeding. A single gregarious female locust can lay 60-80 eggs three times during its average life cycle of 90 days. If their breeding is coterminous with that of the kharif crop, we could well have a situation similar to what maize, sorghum and wheat farmers of Kenya, Ethiopia and Somalia experienced in March-April.

How can these pests be controlled?

Historically, locust control has involved spraying of organo-phospate pesticides on the night resting places of the locusts. On May 26, the Indian Institute of Sugarcane Research, Lucknow, advised farmers to spray chemicals like lambdacyhalothirn, deltamethrin, fipronil, chlorpyriphos, or malathion to control the swarms. However, the Centre had on May 14 banned the use of chlorpyriphos and deltamethrin. Malathion is also included in the list of banned chemicals but has been subsequently allowed for locust control.

Special mounted guns are used to spray the chemicals on the resting places and India has 50 such guns, and 60 more are expected to arrive from UK by the first week of June. Drones are also being used this year.