Czech Billionaire Bets Big on Industries Other Investors Avoid

Daniel Kretinsky's latest contrarian move: U.S. retailers.

by Edward Robinson, Peter Laca, Alexander SazonovAcross the U.S., sales are cratering, bankruptcies are on the rise, and unemployment has hit unprecedented levels. With consumers glued to the couch watching Netflix or commiserating over Zoom, retailers have been especially hard hit. Yet even as the coronavirus pandemic wreaks havoc on American malls and main streets, a billionaire from Prague sees something in the wreckage: bargains.

On May 11, Vesa Equity Investment, a private equity firm controlled by Daniel Kretinsky, a 44-year-old investor little known outside of finance circles, disclosed it had acquired a 5% stake in Macy’s Inc., the troubled department store chain that has seen its stock nose-dive by more than half this year. Then on May 18, Vesa said it had bought 6% of sneaker-seller Foot Locker Inc., whose shares are off by a quarter.

In a filing with the Securities and Exchange Commission, Vesa said it planned to “engage in constructive discussions” with Macy’s. While analysts pondered what that might entail, some had a more fundamental question: Who is this guy?

“I had to look him up,” says David Swartz, an analyst with Morningstar Inc. who covers retailers. “I’d never heard of him.”

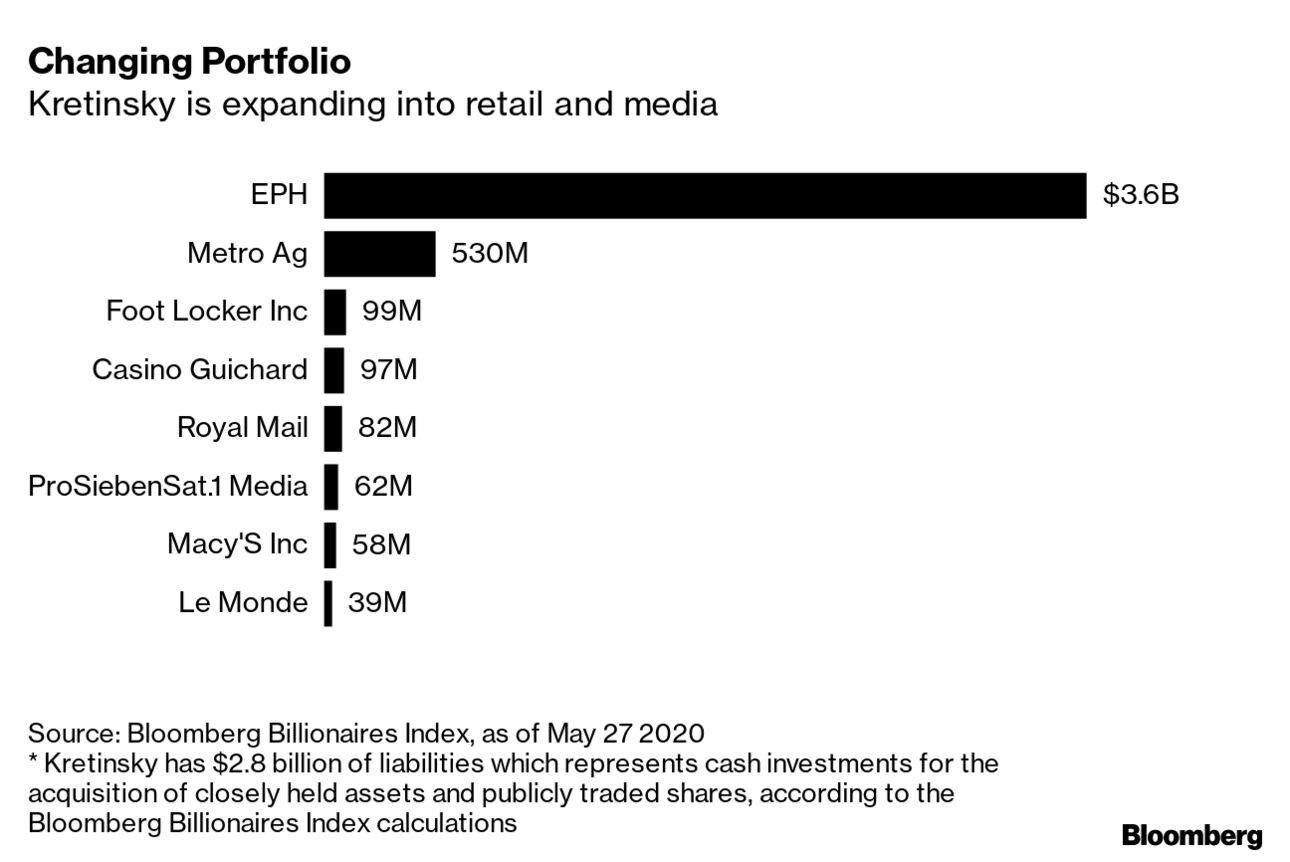

Over the last few years, Kretinsky has emerged as a contrarian financier with a taste for industries others avoid, assembling an eclectic portfolio ranging from power plants and supermarkets to media companies and even the U.K.’s privatized Royal Mail Plc. The strategy has paid off: In the last three weeks, Kretinsky’s net worth has climbed by $100 million, according to the Bloomberg Billionaires Index.

World’s Richest Spend $1 Billion on ‘Bargains of a Lifetime’

Kretinsky can come across as a cold-eyed capitalist unafraid to challenge boards of companies in his portfolio and invest in unfashionable assets such as coal. Yet he also casts himself as a steward of liberal values and independent debate as owner of Czech newspapers and French media properties, including a minority stake in Le Monde, the prestigious Paris daily.

He rarely speaks publicly and grants few interviews to explain his approach, prompting a Polish magazine to dub him the “Czech Sphinx.” Kretinsky, who tested positive for coronavirus in March and worked from home as he recovered from what he said felt like a light cold, declined to comment for this article.

While his eye for value has helped Kretinsky build a $1.8 billion fortune, he’s also suffered setbacks. The journalists at Le Monde have bristled at the ownership of a tycoon who made his money in fossil fuels. And in 2019, the board of the German retailer Metro AG rejected his $6.5 billion takeover bid.

Rather than publicly assail Metro’s management as many activist shareholders might have done, Kretinsky opted to bide his time. He upped his stake in the German company to 29.9% and asked for a board seat, promising to contribute ideas for improving profitability. Despite that manifest patience, opponents shouldn’t underestimate Kretinsky’s ambition, says Josef Kotrba, head of accounting firm Deloitte’s Prague office.

“He’s this soft-spoken, elegant man, and unlike many of his peers, kind of friendly,” says Kotrba, whose office has done work for Kretinsky’s businesses. “You wouldn’t guess he’s a shark.”

Kretinsky got his start in 1999 as a lawyer at Czech private bank J&T, where he earned about $900 a month. Ten years later, he formed his own outfit, EPH, with the backing of partners from J&T and Czech billionaire Petr Kellner, and zeroed in on an energy sector beaten down by the global financial crash.

As the European Union sought to phase out fossil fuels, Kretinsky wagered it would take a long time to wean the region off carbon. So he acquired natural gas pipelines and power plants that burn coal, including lignite, an especially dirty form of the fuel. That paid off as those plants continued to operate. EPH has since moved into renewable energy, logistics, and real estate, and today it comprises 70 companies in almost a dozen countries in Europe, with assets valued at 13.3 billion euros ($14.6 billion).

“We want to make money in industries that are dying because we think they’ll die much more slowly than the general consensus says,” Kretinsky told university students during a 2015 speech in Prague. “Going with the crowd and following trends is always a mistake.”

By 2017, Kretinsky had decided to invest his growing personal fortune outside the energy sector. So he joined forces with Patrik Tkac, the chairman of J&T Banka, to form Vesa, with Kretinsky holding a 53% stake. These days, he’s clearly not following the herd. With stalwarts such as J.C. Penney Company Inc. and Neiman Marcus Group Inc. declaring bankruptcy this month, analysts say a reckoning is at hand for department stores long threatened by Amazon.com Inc. and the decline of the indoor shopping mall.

Even before the pandemic forced Macy’s to close its 775 locations in mid-March, it was struggling to turn a profit and had embarked on a plan to shutter 125 underperforming outlets and boost digital sales. On May 21, the biggest U.S. department store chain, with sales of $25 billion last year, gave a preview of the damage to come, telling investors to expect a $1.1 billion loss in operating income in the first quarter. Foot Locker has been similarly battered and on May 22 reported it lost $98 million in the first quarter, versus net income of $172 million in the same period in 2019.

With both chains starting to reopen, investors will be watching to see how business rebounds in an era of social distancing and anxiety. “What does a store have to do to make you comfortable?” says Sam Poser, an analyst with Susquehanna Financial Group in New York who covers the apparel industry. “There are so many questions yet to be answered.”

Kretinsky has long sought to expand in the U.S., and his decision to buy into the two companies is consistent with his ongoing shift from energy to retail; In addition to his stake in Metro, he is the No. 2 stockholder in French supermarket chain Casino Guichard-Perrachon SA, with a 7% stake.

Still, given the uncertainty around reopening the U.S. economy, even people who’ve long known Kretinsky were taken aback by his decision.

“It is quite surprising, but I am sure there’s more to it than just widening his portfolio,” says Michal Snobr, a Czech investor who used to work with Kretinsky at J&T. “It may be a bet on some future development, like when he bought assets in Germany that everyone dismissed but have turned out to be a great investment.”

In any event, Kretinsky is now a top five shareholder in two of the most famous brands in American retail. Foot Locker, with sales clerks dressed like zebra-shirted referees, has been a staple of malls for more than 40 years. And the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade, with its gigantic inflatable cartoon characters floating through Manhattan toward its flagship store on Herald Square, has been an autumnal ritual since 1924.

In the short term, at least, Kretinsky’s timing is on target. After falling off a cliff in early March, shares of both companies have stabilized in the last month. The Czech billionaire is betting the worst is over.

— With assistance by Lenka Ponikelska