Masking the Future of Well-Being

How collective social behavior shapes pandemic transmission.

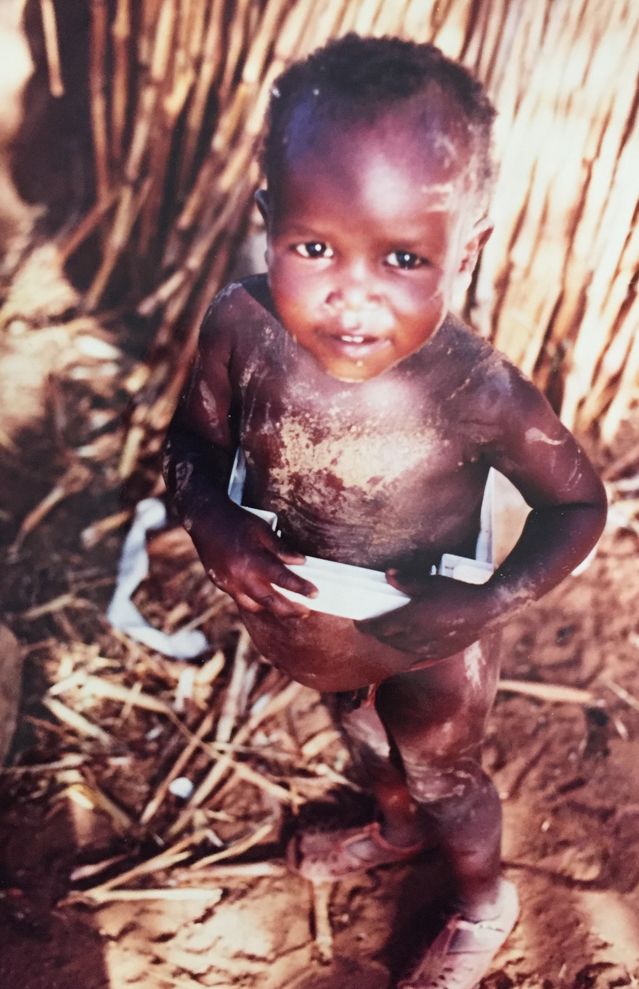

by Paul Stoller Ph.D.In Niamey, the capital of the Republic of Niger, Ramatou Seyni and her two children live in a city-center lean-to fashioned from scrap metal. Her one-room house sits at the edge of a deep garbage strewn gully into which raw sewage flows, which means that a nose-crinkling stench is ever-present in her cramped quarters. Her children, a five-year-old boy and an eight-year-old girl, dress in old dirty clothes. Ramatou, a tall, lean woman with an infectious smile, is a potter. Potential buyers stroll by her house and inspect the pots she routinely arranges on a dirt path in front of her dwelling. In a good year she might earn $300, which is the average per-capita income in the Republic of Niger, one of the poorest nations in the world.

Whenever I have traveled to Niger for anthropological research, I have always walked the city streets—to better know the people who lived on them. On one of my walks several years ago I found Ramatou’s street shop and bought one of her pots. After the sale, she invited me to sit with her in front of her house. We talked for many hours about our families, Niger, and America. She insisted that I come back regularly to fakarey or shoot the breeze. We became friends. I learned a great deal from Ramatou. She was a widow with little expectation of remarrying. She never complained about how difficult it had been for her, a single woman in Niger, to care for herself and her family. Somehow, she managed to feed, shelter, and send her children to school.

Every time I visited, she insisted that I share a family meal. She prepared delicious food: sometimes rice with a spicy fish stew, sometimes a rich millet porridge, sometimes millet paste smothered with an aromatic baobab leaf sauce.

Rematou usually complained that I didn't eat enough of her food. “You have to eat until you are full,” she insisted. “We always make more food than we can eat. That way we can give some food to people who haven’t eaten.”

I once offered her money to help pay for food, books, or school fees. "I can’t take it, Paul,” she told me.

She did take the money I paid for her pots, and I bought a good many of those.

During one visit she made a statement that I'll never forget. “Life is hard here, but we take care of one another.”

Life has been “hard” for a long time in hot, poor, and dusty Niger. People there are hungry. They often have no access to potable water. They suffer from diseases like malaria, typhoid, and hepatitis.

Many infants die before they are two years old. Adults, for their part, often do not survive to old-age. Given these conditions, you’d think Nigeriens would be angry, spiteful, and selfish. During all the years I’ve known people like Ramatou, I have almost never encountered widespread anger, spite, or selfishness. In the midst of mind-boggling poverty, I found generosity, deep dignity, and well being.

In these pandemic times “hardness” has become a global phenomenon. Even in relatively prosperous nations, the novel coronavirus virus has infected millions of people, young and old, many of whom have been hospitalized, many of whom have died. The presence of the virus has changed our social routines. We have to be vigilant, watching what we touch, and making sure to keep our distance from loved ones, friends, colleagues, and strangers. Now that economies are “opening up,” there is the additional social stress about how to behave in public—especially in indoor spaces.

In an indoor public setting, should you wear a mask?

In an indoor public setting, should you ask some who is not wearing a mask to put one on?

In any setting, what is our social responsibility to others in everyday life—especially during this pandemic?

Medical anthropologists and epidemiologists know that in a pandemic the social decision to wear a face mask has profound epidemiological ramifications. As Ben Cowling, head of epidemiology and biostatistics at the University of Hong Kong put it in a May 4 BBC Future article, the airborne persistence of the novel coronavirus "…makes it particularly difficult to suppress transmission in the community… But if everybody is wearing face masks, that would mean infected and asymptomatic people are also wearing masks. That could help to reduce the amount of virus which gets into the environment and potentially causes infections.”

If we confront the pandemic as individuals exercising their “freedom” and “liberty” no matter the biological impact on loved ones, friends, colleagues, or strangers in the community, the foundation of society begins to crack. As those social cracks widen and deepen they may well give way to a potentially horrific dystopian future in which the quest for well being becomes a distant dream. That is why it is important to listen to the voices of people, like Ramatou Seyni, who have confronted the physical and emotional privations of living in a "hard place."

Indeed, the practical wisdom of Ramatou Seyni is a model for social behavior in these pandemic times. Prepare enough food so you can give something to those who haven't eaten. Wear a mask so that you can help to slow the spread of disease and death.

"Life is hard here," Ramatou Seyni says, "but we take care of one another."