Press freedom in Myanmar regresses

by Rodion EbbighausenIncreased arrests of journalists, the partial shutdown of the Internet and the increasing blocking of websites show that the liberalisation of Myanmar's press is in danger.

"On March 30, around half past nine in the evening, ten men in plain clothes came to my home in Mandalay and said they had to interrogate me," said Nay Lin, editor of the online publication Voice of Myanmar (VOM). When Nay Lin followed the men, it turned out that the police were investigating him under the anti-terror law. The accusation: Nay Lin had interviewed the spokesman for the rebel group Arakan Army (AA) in Rakhine, which had recently been declared a "terrorist organization" by the government. The maximum sentence for alleged support of the AA: life imprisonment.

Nay Lin spent ten days in prison, partly in solitary confinement. Then the charges were dropped. It was clear that this had been done in order to intimidate him – and with success: "My colleagues are intimidated. Some have stopped working for VOM. And one of our media partners stopped exchanging content with us, so we lost revenue."

Journalists under pressure

Nay Lin’s case is not an isolated incident. On May 22, 2020, news editor Zaw Ye Htet of the Myanmar news agency Dae Pyaw was sentenced to two years in prison for falsely reporting the death of a COVID-19 patient. The case of the two Reuters journalists and Pulitzer Prize winners Wa Lone and Kyaw Soe Oo, who were arrested and sentenced for alleged violation of the Official Secrets Act 2017, became known worldwide. They were investigating the murder of ten Rohingya in Inn Din village. They spent a total of more than 500 days in detention.

The cases mentioned are only examples. There are many others that prove that targeted action against individual journalists is on the rise in Myanmar. There are still many laws in force in Myanmar that can be used against journalists and thus press freedom. In the two cases mentioned above, these were the Anti-Terror Law or the Official Secrets Act. The coronavirus has now presented another opportunity to muzzle journalists or block websites, as current developments show.

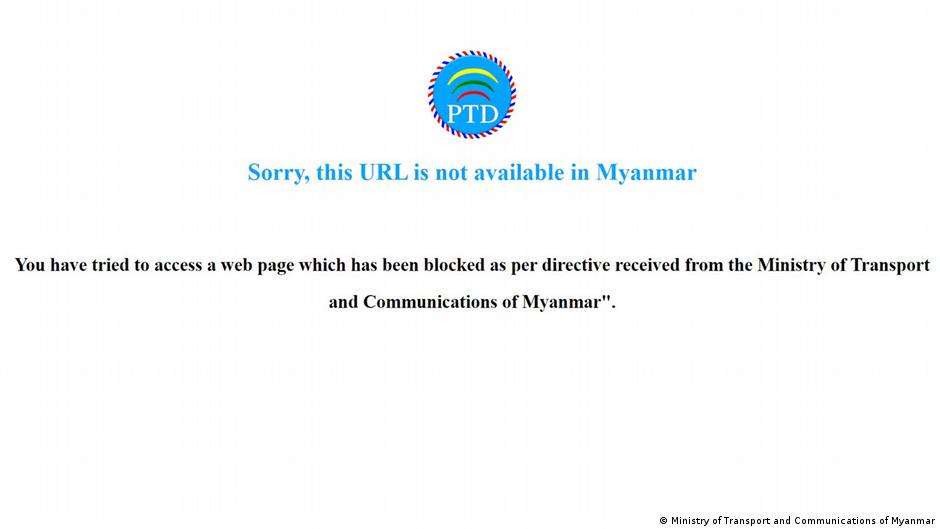

'Sorry, this URL is not available in Myanmar'

At the end of March, Telenor, one of Myanmar's four mobile phone operators, publicly warned that government instructions must be followed and therefore blocked 230 websites. The order came from the Ministry of Transport and Communications. Other network providers, such as Myanma Posts and Telecommunications have also implemented the government order. Even though the details of the blockades vary from provider to provider, it is undisputed that access to certain content has been and is being prevented or at least made very difficult.

Pornographic sites formed the bulk of the 230 blocked sites. However, over 60 sites of critical media such as Voice of Myanmar or Narinjara News, a news portal that mainly reports about the Rakhine State in Western Myanmar were also blocked.

The government justifies the restrictions as measure to combat the spread of false reports on the coronavirus pandemic. A study by the Open Observatory of Network Interference (OONI) in early May 2020 examined this claim. It compared the blocked sites with a list of "fake news" sites created by the Myanmar Press Council. The comparison made it clear that it was not only sites that disseminate fake news that were blocked, but also those that report critically about the government or about conflicts from the perspective of ethnic minorities.

As a further instrument for controlling the media, the government has been implementing an Internet shutdown in parts of the Rakhine and Chin states since mid-2019. In the region, the military repeatedly fights violent battles with the Arakan Army (AA). On May 2, 2020, the internet was reopened in some parts of Rakhine State, but several communities are still cut off from information. The military attributed the blocking of the Internet to the increase in propaganda and inflammatory speech and to the use of the internet by informants of the AA, which endangers the security of the military.

Parliamentary elections and ethnic conflicts

According to Oliver Spencer of the media rights organization Free Expression Myanmar (FEM), the restriction of press freedom through the targeted persecution of individual journalists, the blocking of various portals and the shutdown of the Internet in entire regions is also connected with the upcoming parliamentary elections in November. The government does not want to give the rebels any place in the media.

Tin Tin Nyo, the director of Burma News International (BNI), an umbrella organization of ethnic minority media in Myanmar, finds it noteworthy that the government and military took action against media freedom at the very moment when public attention was distracted by the pandemic. According to Tin Tin Nyo, the number of military offensives against ethnic rebels like the Arakan Army also suddenly increased.

In fact, the new restrictions particularly affect ethnic minority media, which report in great detail and critically on the fighting in Myanmar's civil war zones such as Rakhine. The websites of three BNI members are blocked. "They are small media houses," says Tin Tin Nyo. "It's easy to put pressure on them. Even before these current restrictions, our members have often been forced to self-censor."

Growing criticism

In addition to criticism from the FEM and BNI, 250 civil society groups expressed their concern at the beginning of April: the government was abusing the Corona pandemic to censor legitimate information. They demand an end to the arbitrary Internet blockades and the complete Internet shutdown that has been going on for months in the embattled areas of Rakhine and Chin States.

The measures of the government remind us of times believed to be overcome. Before the opening of the country in 2011 and under the rule of the military government, a strict censorship regime prevailed in the country. Today the media landscape in Myanmar is much freer compared to the period before 2011, but the scope for critical reporting achieved in the years 2013-2017 has been gradually reduced since then.