Achille Mbembe and the fantasy of separation

The latest German uproar exposes a core cleavage in Holocaust memory.

by Jonathan LanzGerman society is once again in an uproar over the Holocaust. This time, however, it has nothing to do with coming to terms with its past. Rather, the current controversy surrounds someone who is generally far away from the continuous debates in Holocaust studies: Cameroonian scholar Achille Mbembe. The storm surrounding Mbembe, a widely-respected public intellectual and scholar of colonial legacies, illuminates one of the major fault lines in Holocaust studies and in Jewish public life: the question of Holocaust exceptionalism.

The widespread controversy surrounding Mbembe began with the publication of his essay “The Society of Enmity,” which first appeared in German three years ago. In one of the essay’s earliest passages, Mbembe compares the case of apartheid in South Africa with the plight of Palestinians in the occupied territories. Later in the essay, he links South Africa’s brutal system of apartheid with the murder of European Jewry, claiming that “the apartheid system in South Africa and the destruction of Jews in Europe — the latter, though, in an extreme fashion and within a quite different setting — constituted two emblematic manifestations of this fantasy of separation.” This linkage led to allegations of antisemitism by individuals such as Germany’s right-wing Free Democratic Party spokesperson Lorenz Deutsch and the rapid defense of Mbembe by prominent intellectuals such as Aleida Assmann and Michael Rothberg.

It should be noted that nowhere in his essay does Mbembe seek to equate the Nazi project of racial murder with the continuing plight of Palestinians. Indeed, he notes that the destruction of European Jews was “extreme” and took place “within a different setting.” However, the fact that such a controversy often arises after the invocation of the Holocaust demonstrates a core cleavage in Holocaust memory: the hazards of viewing the Holocaust as incomparable.

In his 1946 book, L’Univers concentrationnaire [The Concentrationary Universe], David Rousset, a survivor of Neuengamme and Buchenwald, argued that the Nazi camps existed outside of our time and space, in what he termed as the realm of King Ubu, a fictional comedic figure created by French playwright Alfred Jarry. Rousset claimed that the camps existed within this separate universe, where ‘otherworldly forces’ reign; accordingly, we cannot link the atrocities from planet Auschwitz with the everyday injustices of our world. Since the liberation of the camps, there have been individuals who have sought to heighten the injustice of the Holocaust to an incomparable level; to a plain where neither South Africa’s National Party nor Israel’s Likud Party could ever reach.

Rousset is not alone in this position. The President’s Commission on the Holocaust, convened under Jimmy Carter in 1978, wrote that the Holocaust was “a crime unique in the annals of human history, different not only in the quantity of violence-the sheer numbers killed-but in its manner and purpose as a mass criminal enterprise organized by the state against defenseless civilian populations.” This is simply not true. The Holocaust was sadly not a unique crime, and historians and the public alike should reject the dangerous notion that the murder of Europe’s Jews by Nazi forces and their collaborators is above any comparison.

To find similar phenomena we don’t have to look far. In 1915, the Ottoman state deported up to 1.5 million Armenians into the Anatolian interior where they were starved, raped, and deliberately murdered. Even today, nations such as the United States refuse – ostensibly for geopolitical reasons – to properly call this atrocity what it was: a systematic program of mass extermination. A genocide. Similarly, in 1905 the Imperial German Army established a death camp at Shark Island, located in present-day Namibia. Prisoners were repeatedly beaten and killed as part of a larger program of what German General Lothar von Trotha termed a fight against “Unmenschen” [non-humans]. In 1998, German President Roman Herzog refused to apologize or label the killings genocide. To this day, the Herero and Nama are without justice.

If a Presidential Commission was convened on the Herero and Nama genocide, it would read eerily similar to the 1978 report. Both cases saw the systematic destruction of entire civilizations and the murder of “defenseless civilians.”

These examples are only two from a very long list of atrocities which wholly constitute genocide. Conceptualizing the Holocaust as a unique event outside of human history both reduces the suffering of groups such as the Armenians, Herero, and Nama, while distorting the real history of the Holocaust. Birkenau, Majdanek, and Treblinka were all products of their time. They were the result of human ideologies such as antisemitism, fascism, and, on a basic level, white supremacy. We must ground the Holocaust in our world, with all of the moral and historical implications which it brings.

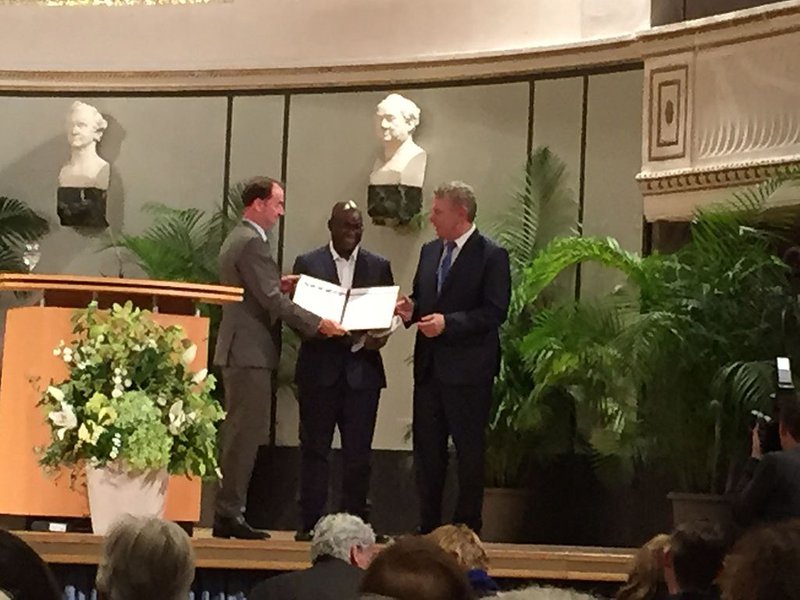

The controversy surrounding Mbembe’s comments reflects the dangers of Holocaust exceptionalism. He is no antisemite. As a celebrated scholar, Mbembe is the recipient of the Geschwister-Scholl-Preis, one of Germany’s top literary prizes for authors who support the values of freedom and moral courage. Furthermore, he is an expert in understanding the ideological mechanisms which undergirded so many of these violent histories. Mbembe’s comments are not antisemitic, but because they threaten the supremacy of the Holocaust as an untouchable atrocity, they generate anxiety. We should not be scared by Mbembe’s comments, but rather embrace his words as a fulfilment of the promise of ‘Never Again.’

After Minneapolis, is the US ‘a failed social experiment’?

The horrific killing of George Floyd has shocked the world and sparked uprising across the US. Join openDemocracy to discuss what this means for the world’s superpower.

Panellists will be announced soon.

This is a change from the previously announced topic. Our discussion on how we will work after coronavirus will be rescheduled.