Boris Johnson may learn that wars don’t always make leaders popular

The British prime minister wants to be a Churchill but is looking more like George W. Bush.

by Paul RogersOn 17 March, in the second of the daily press conferences that have become a staple of British news during the pandemic, Prime Minister Boris Johnson declared war on the novel coronavirus. He announced “steps that are unprecedented since World War Two… We must act like any wartime government… Yes, this enemy can be deadly, but it is also beatable… And however tough the months ahead we have the resolve and the resources to win the fight.”

Harking back to Winston Churchill, the second world war and the ‘spirit of the Blitz’, what Johnson is missing is the nature of political popularity in war, and the manner in which positions of political power can crumble away before governments even realise it.

Last November, he could have been forgiven for thinking a pandemic would meet its match in the UK. That was when the World Economic Forum published a league table of different countries’ planning for a pandemic. The best prepared, out of 195 states, was the US, followed by the UK, with the Netherlands, Australia, Canada and Thailand not far behind.

As openDemocracy has shown repeatedly, though, the UK’s actual performance in the face of COVID-19 has been dire. The contrast is between the advice available, as in the 2018 UK Biological Security Strategy, and the persistent lack of political commitment in implementing it. The government failures have led to considerable concern among Conservative back-benchers and a tetchiness in Downing Street that has even extended to excluding openDemocracy’s James Cusick from asking questions at the daily briefings.

To add to an intemperate political climate, on both sides of the Atlantic those two ‘best prepared’ states are showing themselves to be singularly fractious. Donald Trump will hit out at anyone likely to challenge him and is insisting that lockdown be eased in spite of the death toll having topped 100,000. Johnson is under intense pressure to relax the British lockdown even though there is little evidence that the track-and-trace system for infection control, launched yesterday, is anywhere near ready enough. Moreover he is now immersed in a crisis of his own making over the behaviour of his indispensable special advisor, Dominic Cummings.

Join the COVID-19 DemocracyWatch email list

Sign up for our global round-up of attacks on democracy during the coronavirus pandemic.

There is now a desperate hope that a second wave of infection will be avoided after lockdown is eased, but experience in some countries, including Iran, doesn’t give much cause for optimism. Andrea Ammon, director of the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, has given a blunt warning of the risks ahead. For Johnson’s supporters, the best hope is that a second wave will be avoided, the economy will not tank, the current difficulties over the behaviour of Cummings will recede and the Tory party will hold together.

The war metaphor suggests things will not go their way. Take three wars fought by Western powers since 1945: Indochina, Vietnam and Iraq.

Inglorious war

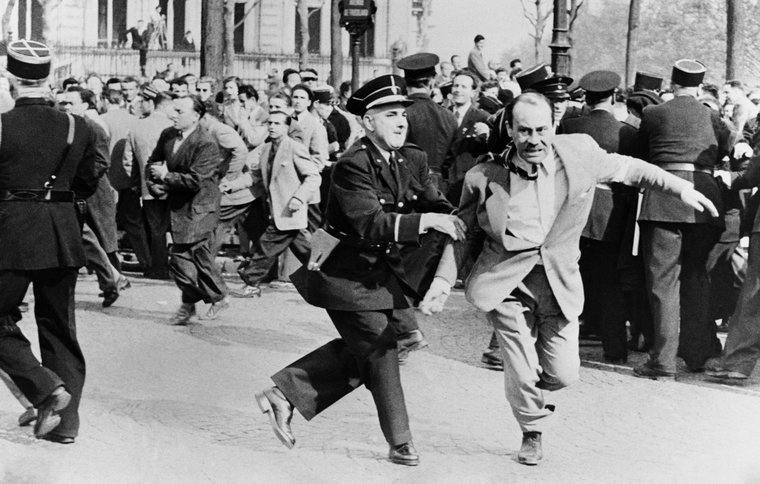

For eight years between 1946 and 1954 the French fought a bitter war against the Vietminh for control of Indochina. In the process the French lost 75,000 troops: most were Foreign Legionnaires and what were termed ‘colonial’ troops, but more than 20,000 were French. As the war became bogged down over its last two years, domestic morale broke. In city districts, towns and even rural areas right across France, just about everyone would have heard of someone killed in the war. The end was abrupt – when the supposedly impregnable fortress of Dien Bien Phu fell to the Vietminh in May 1954, the French accepted defeat.

Public support for US involvement in Vietnam collapsed more slowly, because the country’s losses escalated over the best part of two decades, but the effect was similar. There were 58,000 military deaths and tens of thousands more suffered life-changing physical and mental injuries. The war peaked in 1968 with nearly 18,000 deaths but even as it decreased in the early 1970s the domestic impact across towns and cities deepened. The end result was a thoroughly unpopular war.

The much more recent Iraq war had considerable political significance in both the UK and the US. In the UK, one clear sign of the war was the funeral corteges driven from RAF Lyneham through Wootton Bassett carrying the bodies of the young men and women killed, the whole sad procession shown week after week on national TV. The numbers killed in the eight-year British involvement were small, 182 in all, but the impact on the public mood, combined with intense political disagreement, had a lasting effect.

In the US it was very different. Almost from the start the administration of George W. Bush did its best to minimise the reporting of deaths, with the media kept well away from frequent arrivals of coffins at Andrews Air Force Base. Instead, the impact was incremental. Over the war as a whole the US lost 4,200 soldiers but saw some 30,000 seriously wounded. Because of body armour, battlefield trauma control and rapid casualty evacuation, for every life lost at least seven people would survive; but many survivors had life-changing injuries including loss of limbs and severe face, throat, bowel and genital injuries, some needing life-long 24/7 care.

By 2008 and the end of Bush’s presidency there was personal knowledge of people killed or injured right across the country. This was one of the reasons why Barack Obama could fight his presidential campaign on Iraq as a ‘bad war’ requiring an early withdrawal.

Bitterness

Whether or not the UK gets a second (and third) COVID-19 wave, the death toll is already way beyond the official figure of 40,000 and could well end up double that, which would be more than twice the number of civilians killed in the UK in the entire six years of the second world war. The outpouring of community action, cooperation and support has been extraordinary to see, but there will also be a bitter feeling of a government that has let the country down, and a sense that many thousands of people would still be with us but for government incompetence and mismanagement.

Furthermore, that was the position before the extraordinary behaviour of Dominic Cummings came to light as well as the remarkable response from Boris Johnson. These have resulted in anger and resentment right across the political spectrum and the country, resulting in a perception of ‘one law for the elite and another for the rest of us’. “Do as I say, not as I do” is a dangerous mantra at the best of times, but it is a reasonable assessment that it will long outlive the immediate media storm. With all the deaths and grieving it will have a lasting impact that Johnson will not be able to shake off. His ‘war’ may turn out to have a decidedly two-edged sword.

Stop the secrecy: Publish the NHS COVID data deals

To: Matt Hancock, Secretary of State for Health and Social Care

We’re calling on you to immediately release details of the secret NHS data deals struck with private companies, to deliver the NHS COVID-19 datastore.

We, the public, deserve to know exactly how our personal information has been traded in this ‘unprecedented’ deal with US tech giants like Google, and firms linked to Donald Trump (Palantir) and Vote Leave (Faculty AI).

The COVID-19 datastore will hold private, personal information about every single one of us who relies on the NHS. We don’t want our personal data falling into the wrong hands.

And we don’t want private companies – many with poor reputations for protecting privacy – using it for their own commercial purposes, or to undermine the NHS.

The datastore could be an important tool in tackling the pandemic. But for it to be a success, the public has to be able to trust it.

Today, we urgently call on you to publish all the data-sharing agreements, data-impact assessments, and details of how the private companies stand to profit from their involvement.

The NHS is a precious public institution. Any involvement from private companies should be open to public scrutiny and debate. We need more transparency during this pandemic – not less.

By adding my name to this campaign, I authorise openDemocracy and Foxglove to keep me updated about their important work.