Nationalisation of Reserve Bank: What SA can learn from New Zealand

by Hlengani MathebulaNew Zealand’s handling of policymaking regarding its central bank holds lessons for SA when it comes to plans to nationalise Reserve Bank, writes Hlengani Mathebula

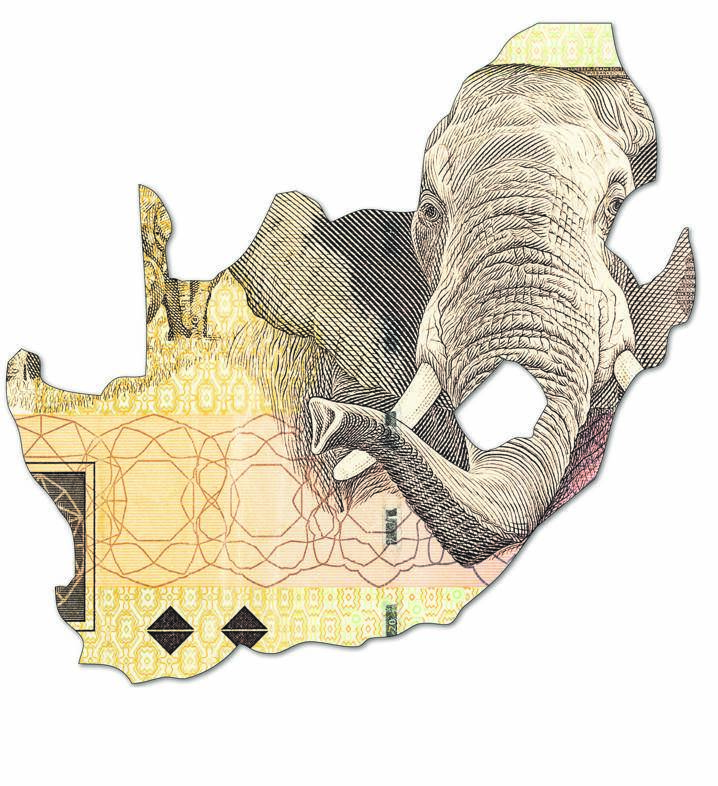

As the South African economy has sunk deeper into a quagmire of low growth and rising unemployment, there has been greater focus on the SA Reserve Bank.

First, the ANC resolved at its 2017 national conference to nationalise the Reserve Bank.

Since then, President Cyril Ramaphosa has said publicly, at least twice, that government would implement the ANC’s resolution.

He did, however, say in May last year that the nationalisation of the Reserve Bank was desirable, but would come at cost, which “given our current economic and fiscal situation is simply not prudent”.

That situation is worse now than in May 2019, and will worsen further, given the hit the country’s economy and government finances have taken from the Covid-19 coronavirus pandemic and measures aimed at flattening the its curve.

There have been suggestions that the Reserve Bank should finance the budget by buying government bonds, a proposal most recently backed by none other than the deputy minister of finance.

The bank is among a handful of central banks globally that have private shareholders. Some of these central banks have a combination of government and private shareholding.

Other than the fact that the private shareholders in the Reserve Bank are a historical anomaly, the proponents of the bank’s nationalisation have not put forward a cogent case as to what public policy would be achieved by nationalising the Reserve Bank, which could not be achieved under the bank’s current governance arrangements.

That situation is worse now than in May 2019, and will worsen further, given the hit the country’s economy and government finances have taken from the Covid-19 coronavirus pandemic and measures aimed at flattening the its curve.Hlengani Mathebula

I am not going to go into the merits or demerits of the ANC resolution.

Nor will I go into whether forcing the Reserve Bank to finance government is sensible or not.

My purpose today is to focus on what South Africa can learn from New Zealand about public policymaking, especially as it relates to the Reserve Bank.

I have chosen New Zealand because that country’s approach sets a very high standard for transparency and places evidence before the public for its consideration.

I focus on this because it provides the country with a framework for ensuring that the implementation of the ANC resolution in the future is done prudently, but, most importantly, that it is informed by sound economic and public policy evidence.

But before I get to the New Zealand lessons, let me explain the basics of the Reserve Bank shareholding.

In the first instance, no shareholder or their associates can directly or indirectly own more than 10 000 shares in the Reserve Bank.

Also, each shareholder has one vote for every 200 shares they own, which means that a shareholder owning the maximum 10 000 shares has 50 votes.

A shareholder who is “not ordinarily resident in South Africa” is not allowed to vote.

In addition, owning shares in the Reserve Bank does not come with the same rights one would have as a shareholder in a company listed on the JSE.

This is because the rights of shareholders in the Reserve Bank are heavily restricted by law to a few areas relating to a few things, all focused on the activities taking place at the bank’s annual general meeting, one of which is the election of seven nonexecutive directors.

Read: Reserve Bank cuts repo rate to 4.25%

Even these seven directors are drawn from a list vetted by a panel chaired by the governor of the Reserve Bank.

The remaining eight directors, including the governor and three deputy governors, are appointed by the president of the Republic of South Africa after consultation with the minister of finance.

The other business of shareholders at the AGM is the consideration of the minutes of the previous annual meeting, the appointment of external auditors and the approval of the remuneration of auditors for the financial year just ended.

Of course, shareholders have to sit through the governor’s address and are then offered something to nibble and drink.

Now let’s turn to New Zealand. In November 2017, the New Zealand government announced a review of the Reserve Bank of New Zealand Act, primarily to ensure that the country had the most efficient and effective monetary and financial policy frameworks.

A month later, the minister of finance appointed an independent expert advisory panel “to support and advise the officials undertaking the review”.

The process was split into two phases, the first focusing on improving the bank’s monetary policy framework.

Final Cabinet decisions on the first phase were announced in March 2018.

These included the decision requiring monetary policy decision-makers to give due consideration to “maximum sustainable employment” alongside price stability – the so-called dual mandate.

Most people would, in our context, refer to inflation targeting, but inflation targeting is merely a means to an end, which is price stability.

In addition, Cabinet also approved the creation of a monetary policy committee (including a minority of members from outside the bank) as the decision-maker on monetary policy, a decision that historically vested in the governor of the bank.

The steps to the Cabinet decision involved the submission of the panel’s recommendation, the review and comment on these by the Treasury and the Reserve Bank.

Read: Put nationalisation of the Reserve Bank on hold – Mashatile

The panel’s recommendations as well as the comments by Treasury and the bank were submitted to Cabinet by the minister of finance.

All of the documents relating to the decision by Cabinet were made public.

These include the panel’s report, the Treasury’s paper to Cabinet containing the panel’s recommendations and the comments on those recommendations by the Treasury and the Reserve Bank.

The minutes of the panel’s two meetings were also published. All of the advice received from experts other than the panel was also made public and can be read on the New Zealand Treasury website.

Phase two of the review, focusing on the financial policy framework, is under way.

The panel has been expanded to add more relevant expertise. Phase two exhibits the same level of transparency.

There is no reason South Africa cannot emulate New Zealand, specifically when it comes to the SA Reserve Bank.

The point here is not whether government has a right or not to nationalise the Reserve Bank, nor is it whether the bank should be forced to finance government or not.

At stake is whether government takes citizens seriously enough to explain the thinking behind its decisions.

As the New Zealand approach shows, government can go several steps further. It should appoint a panel of experts to interrogate the nationalisation decision – its benefits to South Africa as well as its risks.

Should such a panel find that it makes sense for government to buy out the shareholders of the Reserve Bank, it should recommend what the best way of doing it would be.

There are many questions, but three are the most crucial. Firstly, how would the Reserve Bank shares be valued?

The nationalisation of the Reserve Bank and the proposal that the bank should finance government are probably the most significant economic policy decisions since 1994Mathebula

The second relates to the evaluation of Reserve Bank shares, and the risk that foreign shareholders will take the decision by government to buy them out to international tribunals where they will seek substantially greater compensation than the price at which Reserve Bank shares have traded.

This happened when the Bank of International Settlements, commonly referred to as the central bank of central banks, bought out private shareholders.

Private shareholders sued for a higher price and, as a result, the buyout took almost five years to complete.

The third relates to the risk that nationalisation poses to the Reserve Bank’s independence and what needs to change to ensure that full government ownership does not diminish the bank’s independence. All of these issues should be put in the public domain.

The same applies to the noises being made about the Reserve Bank financing government. What would such a step mean in practice? Which countries have done this, and with what outcomes?

As things stand, there has been no interrogation of these issues to inform the decision, so that as a country we walk into it knowing full well what the risks are.

The nationalisation of the Reserve Bank and the proposal that the bank should finance government are probably the most significant economic policy decisions since 1994.

They shouldn’t be taken lightly, without due consideration of the balance of evidence, including their risks, but also with knowledge of the benefits that will probably accrue to society as a result of their implementation.

In addition, from a public policymaking point of view, this balance of evidence should be put before the public, as well as the reasoning of those who are pushing for them.

Mathebula is a managing partner at Cornerstone Capital Partners and former group head of strategy and communications at the SA Reserve Bank