WhatsApp with the new grants? GovChat flooded by millions of messages

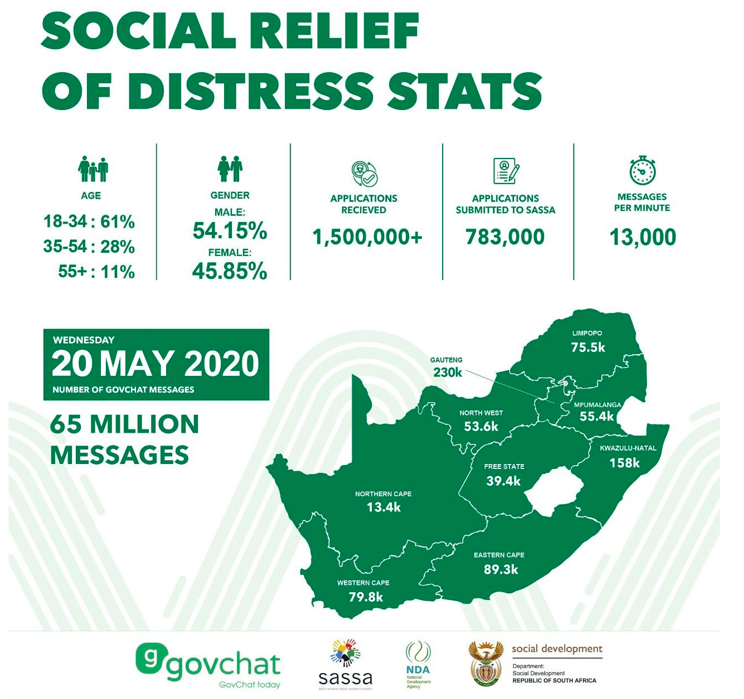

by Fiona Anciano, SJ Cooper-Knock, Mmeli Dube, Mfundo Majola, Boitumelo M PapaneMore than five million applications have been made to the South African Social Security Agency, Sassa, for Social Relief of Distress grants during the lockdown – 1.5 million of those on messaging services such as WhatsApp and Facebook, with more than 65 million messages received in total.

Times of crisis are often periods of increased intervention by government, businesses and civic organisations. These interventions deserve our attention not just because their immediate impacts can be immense, but also because the laws, regulations and practices forged in crisis tend to live on long after that crisis has passed. Usually, the afterlives of these interventions are a cause for concern: emergency regulations granting expanded powers, for example, which never leave the law books. But sometimes, interventions are a cause for hope.

CLOSE

The South African government’s Social Relief of Distress grant (SRD) was one such intervention. Announced in April, this R350 monthly payment was targeted at those without employment or any other grant support. Across Cape Town, the 70 participants of our Lockdown Diary Project gave the measure near-universal support. A diverse group drawn from the city’s occupied buildings, informal settlements, townships and suburbs, they have often disagreed about the government’s interventions. Here, however, they were all but united.

“I think the government’s decision to increase social grants was a good idea to assist beneficiaries as they may not be able to hustle during lockdown,” reflected Khaya in Khayelitsha, one of Cape Town’s poorer townships. “This will make a huge difference in their lives.” Judy, in the affluent suburb of Newlands, agreed, ‘‘I think it is good that social grants are being increased… these increases are long overdue.”

Display Adverts

Whilst the SRD as it stands is extremely limited, several commentators were also optimistic that this crisis-based intervention might form the foundation for a basic income grant in the longer term. But while support for expanded grants is strong, implementing the roll out in the midst of a crisis was never going to be simple. Changing the amounts that grant recipients receive – as the government did with the Child Support Grant – is one thing, but establishing an entirely new, means-tested grant during a health crisis, is an altogether more complicated affair.

Here again, new precedents were set, as the government turned to digital platforms including email, Facebook Messenger, WhatsApp and USSD to administer the grants. In a middle-income country like South Africa, this move is not without its challenges.

The SRD grant is targeted at those on the economic margins, who are most likely to be on the wrong side of the global digital divide. Currently, only one-third of South Africans own a smartphone, and data charges in South Africa are some of the steepest on the continent. Moreover, implementing new systems in a time of crisis is risky because poorer citizens may find reliable information harder to access. When applications for the grants opened earlier this month, big questions around the viability of the government’s strategy remained.

Initially, those questions seemed founded: the first few days of roll-out were characterised by confusion and system failures. “A lot of people have been asking me how one can get the grant, but my answer is always the same – ‘I do not know either’,’’ reported Lwando, a diarist from Imizamo Yethu. Others had got word about the WhatsApp application but were frustrated by the process.

“The new social grant roll out process is a waiting game and their system is not responsive,” wrote Siphenathi, from Khayelitsha. “Someone close to me has sent several emails and WhatsApp messages to the number that was circulating around Facebook,” he said. At that point, they had heard nothing.

On the one hand, the SRD’s system failure was testament to the trade-off between getting systems perfect and “getting money out” in times of crisis. On the other, it was a positive sign that the digital divide was (at least in part) being bridged: the system’s limitations were due to an overload in the first 24 hours, with over 14.2 million messages coming through the WhatsApp channel alone, sometimes at a rate of 100,000 per minute. GovChat, who manage the WhatsApp and Facebook platforms for the government, had to make an urgent request to Amazon Web Services for greater data centre capacity to handle the spikes. Eldred Jordaan, CEO of GovChat, reports that this was the first time such a request had ever been made.

Since its data capacity has expanded, GovChat has processed 65 million messages initiated through both its WhatsApp and Facebook messaging channels, as users go through the application process. Complete applications are coming through at a rate of 30,000 per day, with 1.5 million having been made in total. When combined with applications made through other channels, Sassa has received a total of five million applications for the SRD grant. What proportion will be paid out is yet to be determined.

Display Adverts

In part, the bridging of the digital divide is likely to have been strengthened by the fact that GovChat has allowed users to apply on behalf of others. This can help to mitigate the barriers to access caused by illiteracy or a lack of a phone. As well as proxy applications, borrowing or sharing phones may also be broadening people’s access to digital platforms. In 2018, a relatively high number of households had at least one phone at home that was able to access the internet – ranging from 42% in Limpopo to 68% in Mpumalanga.

Of course, questions and challenges remain: power dynamics are likely to shape proxy applications and phone sharing; data costs on secure platforms remain a key issue, with many applicants dropping off when they have to move from WhatsApp to a secure-form portal; and, as with all government interventions, steps will need to be taken to ensure that the increased visibility people gain when they are “counted” by the system does not lead to intentional or unintentional forms of exposure or exploitation. Attempts to tackle some of these issues are already underway. GovChat, for example, is currently in talks with mobile networks to zero-rate their platforms and those of similar providers. Others will need to follow.

As with every crisis, the Covid-19 pandemic has been the site of intense intervention by multiple actors. Neither the SRD nor its administration has been perfect. Given the limitations of politics and the context of the crisis, they were never going to be. Nonetheless, they offer foundations upon which a fairer and more efficient grant system can be built. The task ahead is to realise that potential. DM

For more information and to read more blogs go to Lockdown Diaries. The Lockdown Diary Project is run by a team of researchers from the University of Edinburgh and the University of the Western Cape.

Fiona Anciano is an associate professor at the University of the Western Cape (UWC); Sarah Jane Cooper-Knock is a lecturer at the University of Edinburgh; Mmeli Dube is an activist and PhD candidate at UWC; Mfundo Majola is a master’s candidate and researcher at UWC; and Boitumelo Papane is a researcher and master’s candidate at UWC.

Fiona Anciano, SJ Cooper-Knock, Mmeli Dube, Mfundo Majola, Boitumelo M Papane

Comments - share your knowledge and experience

Please note you must be a Maverick Insider to comment. Sign up here or sign in if you are already an Insider.