CNN Is Picking Ratings Over Ethics

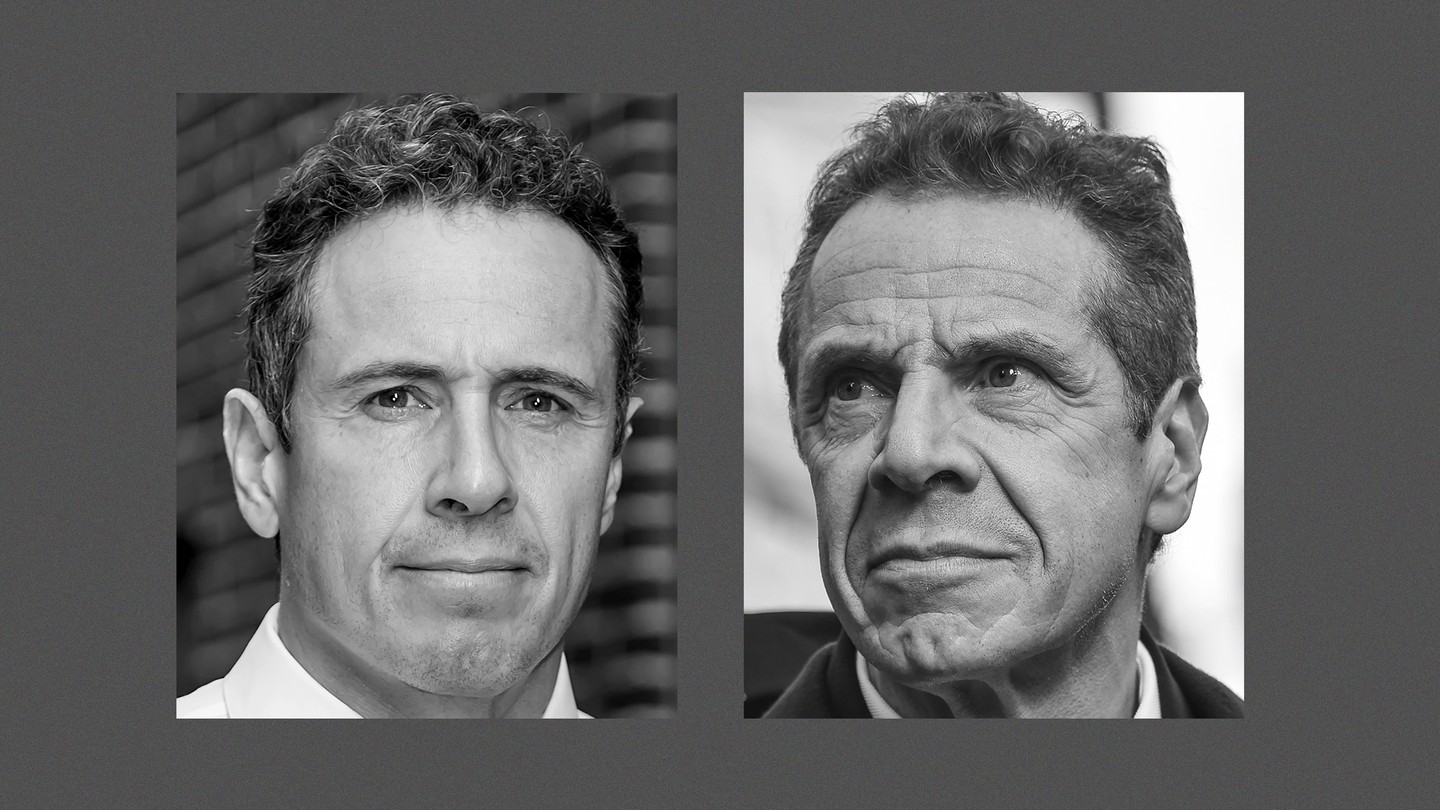

by https://www.facebook.com/david-a-graham-318249352182, David A. GrahamAmerica doesn’t have a hereditary aristocracy—it just has members of the same families who occupy powerful positions from generation to generation. Consider the Cuomo family. Mario, the patriarch, rose from humble circumstances in Queens to become the governor of New York. One of his sons, Andrew, now fills the same job; Andrew’s younger brother, Chris, is a high-profile CNN anchor.

For a time years ago, CNN allowed Chris to interview the governor, despite the obvious questions about whether any younger brother could ever conduct an evenhanded interview of his big brother. (As anyone with siblings knows, the problem is as apt to be excessive toughness as going too easy.) Chris Cuomo defended the topics of these interviews as nonpolitical, and insisted that the problem was one of appearance, not substance. Still, CNN heeded the critics and banned Chris Cuomo from interviewing Andrew Cuomo from 2013 until March 2020, amid the COVID-19 pandemic.

With the New York governor at the heart of the coronavirus story, the rules were relaxed, and the Cuomo brothers began speaking on air regularly. The interviews were funny, as the brothers dredged up old beefs, and became poignant when Chris contracted COVID-19. It was easy to see what was gained: CNN got must-watch TV, and the governor’s office got a chance to humanize a politician more respected (usually grudgingly) than loved. With a little distance, it’s clear what was lost too: accountability for New York’s troubled response to the crisis.

From the start, the tension between the brothers made the encounters entertaining. They quarreled over who is their mother’s favorite child, who works harder, who’s better on the basketball court, and whose clothes fit better. Even for the most jaundiced viewers, the segments were hard not to enjoy. There was a certain voyeuristic charm, too, the Associated Press noted: “It gives viewers sitting at home a glimpse at the dynamics of a family other than their own.” Then Chris contracted COVID-19, adding drama and pathos. Andrew was clearly affected by his brother’s illness; Chris’s appearances from his basement, even while sick, helped people who might not yet have known anyone infected with COVID-19 to see what the illness was like. Viewers were riveted, and Cuomo’s show saw its ratings double from a year before.

Even the most heartwarming content tends to glance off the hardened carapaces of the scolds who enforce journalistic ethics, and indeed, there were occasional complaints. But the canniest critics at the nation’s big papers were cautiously approving. “To a nation inured to nepotism by the likes of First Son-in-Law Jared Kushner spouting ill-informed policy views from a White House podium, this is pretty harmless stuff,” wrote The Washington Post’s Margaret Sullivan. In The New York Times, Ben Smith wondered whether this sort of ethical looseness was simply the next evolution of the press, and might actually improve faith in the news:

But the biggest shift may be the one Mr. Zucker and the Cuomos are now leading. They are, in their way, answering the endlessly debated question of how to restore trust in media. Do you strive to project an impossible ideal of total objectivity? Or do you reveal more of yourself, on Twitter or on Instagram and in your home?

In the past week, there’s been some backlash against the brother act after Chris brandished oversize swabs, like the ones used for coronavirus testing, to mock the size of Andrew’s nose. Meghan McCain, another media beneficiary of the American aristocracy, was particularly incensed. It’s funny that this is what set off complaints, because it’s the same sort of joshing that made the segments so popular in the first place.

The bigger problem is the ethical one that the strictest scolds foresaw in the first place. As a clearer picture of New York’s handling of the pandemic emerges, it’s evident that the perception of Andrew Cuomo’s competence and the reality of his performance are at odds. And yet, in his most high-profile media appearances during the worst of the pandemic, the governor was not being grilled on the Empire State’s failings. Instead, Chris Cuomo was trying to pin him down on whether his brother’s supposedly heroic leadership might make him think about running for president.

Andrew Cuomo’s ratings shot up an astonishing 32 points during the pandemic, per FiveThirtyEight, giving him his best polling in seven years. Chris Cuomo’s CNN colleague Chris Cillizza could barely contain his own enthusiasm: “Thrust into the national spotlight by his state’s status as the epicenter of the coronavirus outbreak in the United States, New York Democratic Gov. Andrew Cuomo has rapidly become one of—if not the—single most popular politician in the country for his handling of the pandemic,” Cillizza wrote. “Cuomo’s poll numbers are, literally, unbelievable.”

The CNN performances were not the only reason that the governor’s ratings were up. Leaders in the midst of crisis almost always benefit from a rallying effect. (Donald Trump right now is a notable exception.) Andrew Cuomo also profited by comparison with the president; while Trump gave unhinged press conferences at the White House, the governor’s appearances were a model of sober and calm leadership. As for the interviews themselves, no one should begrudge the brothers their love for one another. Nor is it wrong, per se, for CNN to seek higher ratings. After all, the goal of journalism is to convey information, and the greater the audience, the better that information spreads. The problem comes when the efforts to juice ratings start to get in the way of accurate journalism that holds officials accountable.

While Andrew Cuomo was benefiting from heart-string-tugging segments on CNN, his state was struggling. Like Trump, Cuomo had promised that COVID-19 wouldn’t be as bad here as elsewhere; like Trump, he didn’t have to wait long to be disproved. Experts said that New York City was always likely to become a center of the virus because of its constant flow of people, size, and density, but as The New York Times reported, “initial efforts by New York officials to stem the outbreak were hampered by their own confused guidance, unheeded warnings, delayed decisions and political infighting.” Promised contact tracing never materialized. Shutdowns came late, and over the governor’s hesitations. Journalism that truly aims to restore trust in media would hold Andrew Cuomo to account for these missteps.

When Cuomo has faced such questions—mostly from reporters who don’t share his last name—he has bristled, blaming a range of other bodies and agencies. As with Trump, he’s not entirely wrong: The federal government and the World Health Organization, among others, did badly botch the crisis. But that doesn’t absolve him of responsibility.

Meanwhile, some other states have performed much better than New York in the face of the pandemic, but their governors haven’t gotten the same kind of adoring media attention. It’s a long-standing media critique that stories in New York and Washington, D.C., get attention disproportionate to stories elsewhere in the country, but that’s not the only factor at play here. If they wanted to share the spotlight, perhaps Governors Jay Inslee of Washington and Mike DeWine of Ohio should have considered having brothers with plum TV gigs.