Taking a break for beauty

Harvard Art Museums uses works from its collections to help doctors decompress

by Colleen WalshDavid Odo from the Harvard Art Museums led a virtual conversation with a group of radiologists on a recent afternoon. The topic? A likeness of singer and songwriter Stevie Wonder.

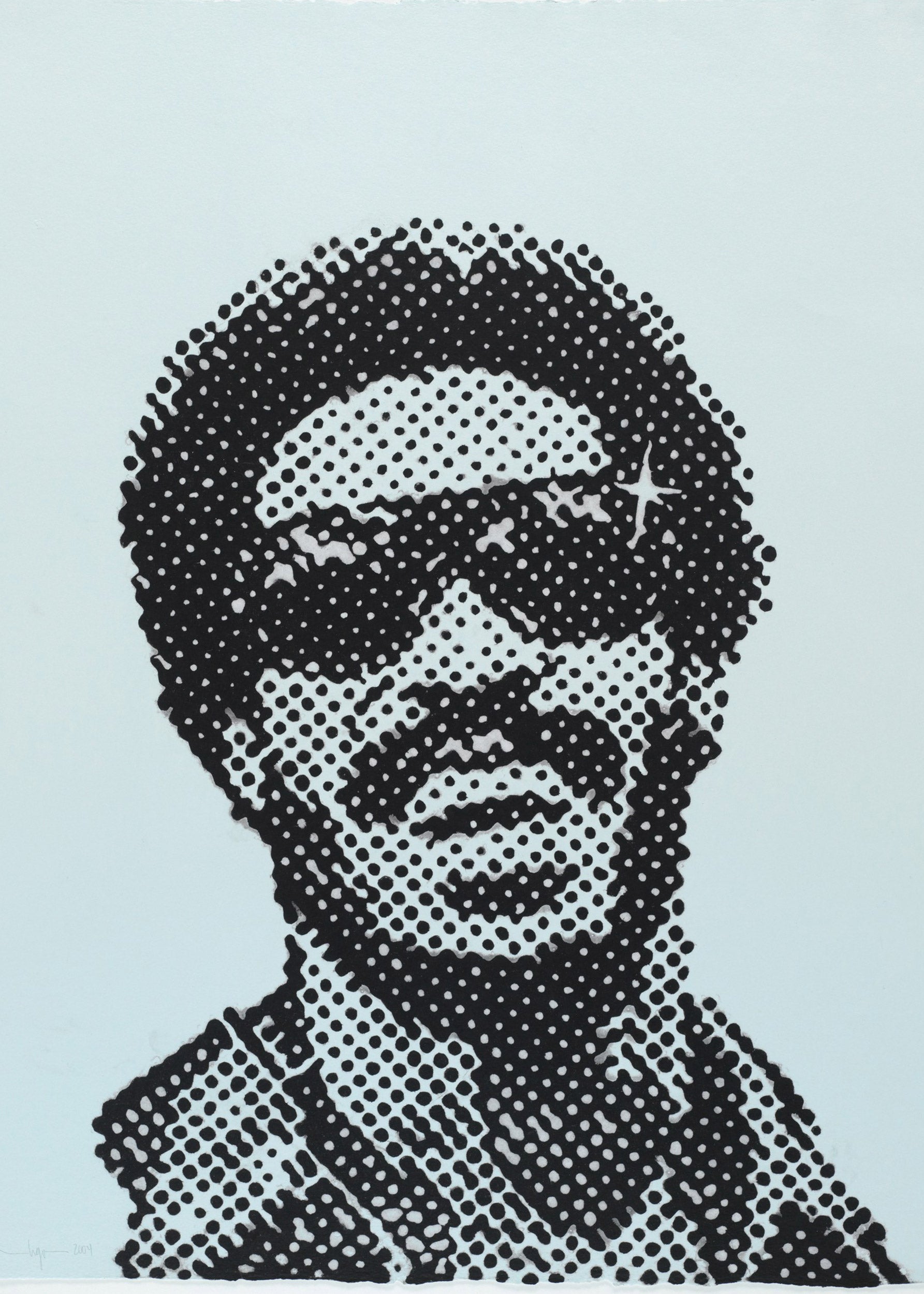

In particular, the conversation focused on the museums’ 2004 print by conceptual artist Glenn Ligon titled “Self-Portrait at Eleven Years Old” based on the cover of Wonder’s 1977 compilation album, “Looking Back.” To begin the session, Odo noted Ligon’s use of a familiar image in a new way and wondered why the artist — whose work frequently addresses questions of identity — called his close rendering of the cultural icon a self-portrait. He then asked participants whom they aspired to be like at age 11. (“My mother” and “Michael Jackson” were two of the answers.)

The session was one of the museums’ 30-minute art breaks — informal, virtual get-togethers organized by the museums’ staff that focus on looking and interpreting and are designed to help the doctors briefly disengage from the pressures and stresses of their work during the coronavirus pandemic. As the illness raged in Massachusetts, Odo led the brief breaks for small groups of doctors from local hospitals, each time examining a different work from the museums’ vast collection, and tying the art to a particular theme. The format is casual and conversational and includes a short introduction followed by time for comments and questions. With engagement the goal, there are no wrong answers.

“The idea that physicians should be allowed to feel good in the midst of the pandemic, the importance of self-care, and worries about burnout are really serious issues,” said Odo, the museums’ director of academic and public programs. “I think anything that the museums can do to help is a good thing to be focusing on right now.”

In choosing Ligon’s homage to Wonder, initially there was no overarching idea to explore, Odo confessed. It was simply a matter of feeling good. He landed on the artist’s work after hearing the singer’s 1965 hit single “Up-tight (Everything is Alright).” In the 1960s the term “uptight” carried the additional meaning of “excellent” or that things were going well, Odo said. “Hearing that song really changed my mood,” he said, “and so I chose that print as a way to share that possibility with everyone. And it was wonderful to see how the discussion grew in interesting directions, touching on self-fashioning and appropriation.”

Fiona Fennessy, a radiologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, called the online meet-ups “an important means of interaction with colleagues and trainees on a level that is far removed from medicine.”

“It allows us to focus on something of beauty, oftentimes old,” she added, “that continues to inspire.”

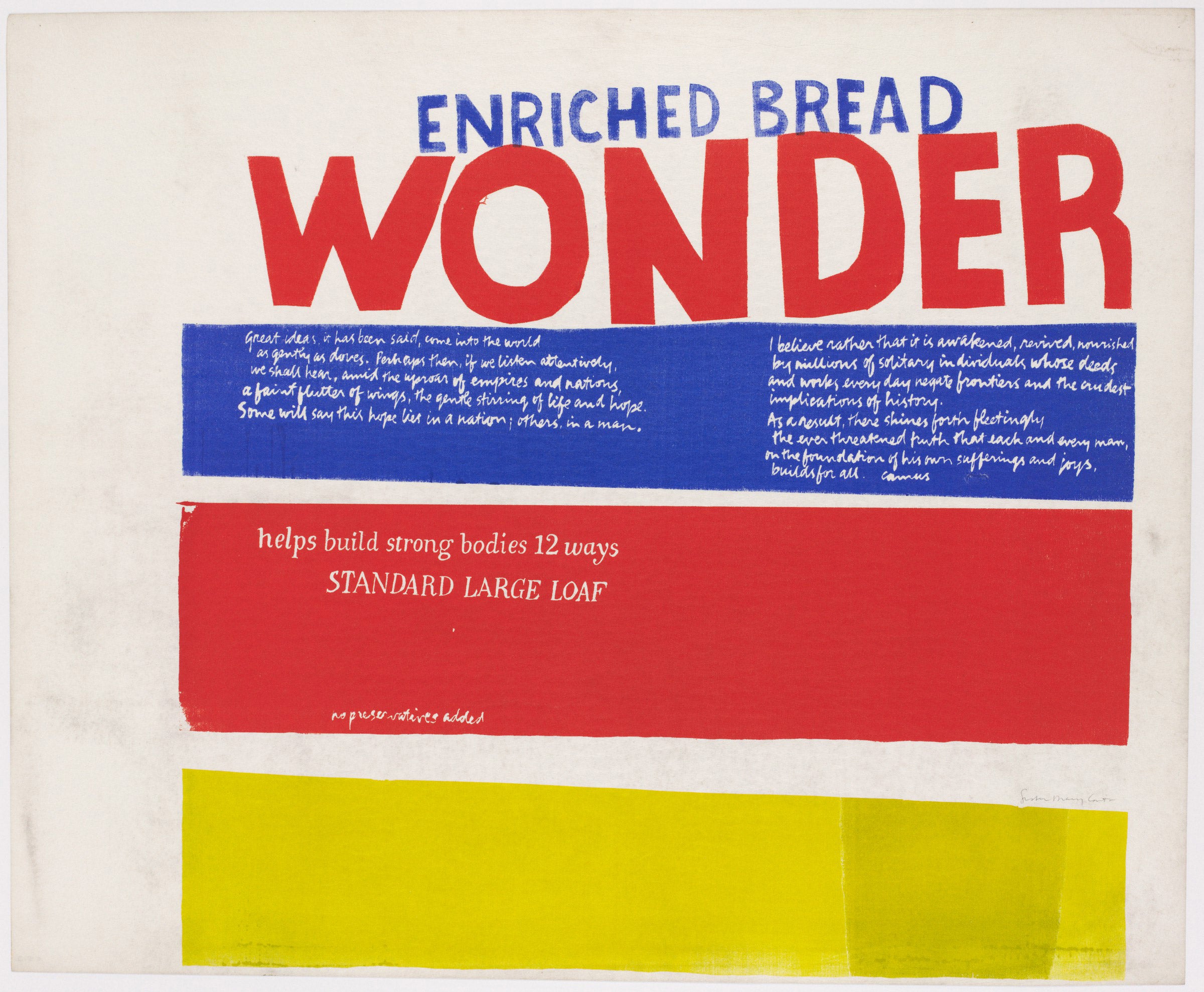

Renée Sintenis’ 1930 work “Daphne,” a bronze sculpture of the beautiful nymph whose father changes her into a laurel tree to save her from the advances of the Greek god Apollo, inspired a conversation about transformation, said Odo, and the need to transform the way we live in the time of COVID-19. A quirky silkscreen by the nun and artist Corita Kent titled “enriched bread” brought up notions of resiliency and hope during times of crisis. The work blends images from a Wonder Bread wrapper with uplifting words from a collection of essays by French philosopher and author Albert Camus (known for his bleak novel “The Plague”). Kent created the piece in 1965 as the U.S. increased its military commitment in Vietnam, “when it seemed like the world was falling apart,” said Odo. The artist’s mix of advertising images, bright colors, and Camus’ inspiring lines “[hope] is awakened, revived, nourished by millions of solitary individuals whose deeds and works everyday negate frontiers and the crudest implications of history,” encourages the viewer to think differently.

“It asks us to reexamine the quotidian,” said Odo, “to think deeply about things we might take for granted. And it engenders a kind of hope that was as poignant then, as it is now.”

The recent art breaks grew out of an earlier, ongoing collaboration between the museums and Hyewon Hyun, a radiologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital who leads a group of radiologist residents in nuclear medicine and diagnostic radiology. A few years ago, as she thought about their work of looking at and interpreting radiologic images and trying to understand what their findings “mean for the patient,” Hyun had an idea.

“When we go to a museum, we often sit in front of something and try to discover what and why it is, exploring our thoughts but also feelings about what we see,” said Hyun. “In the same way, we look at radiologic images and try to discover what we see and why. Then I started to think about how similar, yet different, looking at art and radiologic images is, and how we could learn from looking at art.”

Odo was eager to help. Together they worked with the museums’ staff to create “Seeing in Art and Radiology,” a more intensive curriculum designed for imaging physician trainees composed of four three-hour sessions at the museums.

“It was a great opportunity to really dig deep into the way artists have thought about issues like empathy and compassion by really trying to push the participants to come up with their own interpretations of pieces in the collection and to have them make connections to their own medical work,” said Odo.

Odo and Hyun said the program they created in 2018 was also a way to help radiologists-in-training focus their gaze without worrying that a patient’s health could depend on what they were seeing. The current art breaks function in a similar way, they said, by allowing doctors to step away from their work for a few minutes and just enjoy the art that appears on their computer screens.

“We really just wanted to use art to give them a brief respite from this ongoing uncertainty and stress,” said Hyun.