Droplets created by speech could contribute to COVID-19 spread, new study suggests

by Louisa CockbillDroplet clouds emitted during 1 min of loud speech by an individual infected with the SARS-CoV-2 virus could contain more than 1000 virus particles – according to new calculations done by scientists in the US. This work, alongside observations that these speech-generated droplet clouds persist in a confined space for 8-14 min, supports suspicions that COVID-19 may be transmitted when infected individuals speak.“This direct visualization demonstrates how normal speech generates airborne droplets that can remain suspended for tens of minutes or longer and are eminently capable of transmitting disease in confined spaces,” write the team in a paper in PNAS Brief Report describing the work.

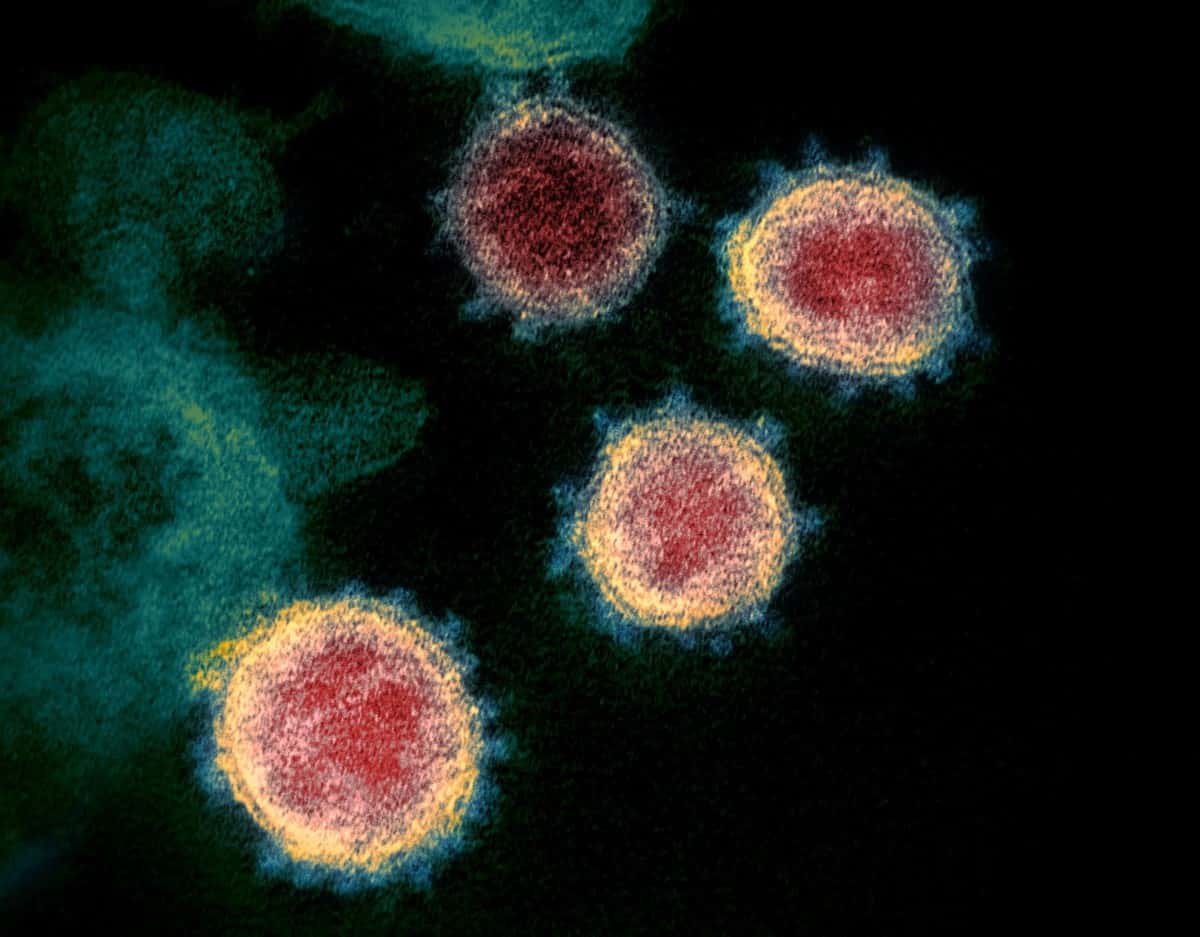

The piggybacking of viral particles (virions) in droplets generated by coughing and sneezing is a recognized route of respiratory virus transmission. However, the role of fluid droplets emitted during speaking is less-well known. Given the current COVID-19 pandemic, this spoken transmission route is attracting considerable attention, particularly in relation to spread from asymptomatic carriers.

Philip Anfinrud and Adriaan Bax’s biochemical physics teams at the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) (part of the National Institutes of Health) in Bethesda, Maryland recently made high resolution visualizations of droplets produced when a person speaks. They described this work in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Visualizing saliva spray

To observe droplets after they are produced by speech, the NIDDK teams used a laser and optics visualization system. The droplets were created by having a person repeat the phrase “stay healthy” several times (with short delays in between) into the “speaker port” of a cardboard box and then capturing the crossing of the droplets through a sheet of intense laser light. The high sensitivity of the system enabled the teams to detect small droplets, 20-100 micron in diameter, and so record a higher volume of droplets than previous studies.

Now the researchers have quantified those experiments to assess the potential for speech droplets to transmit SARS-CoV-2 viral particles in an enclosed environment. In work described in a PNAS Brief Report, Anfinrud and colleagues used an improved experimental setup to derive quantitative estimates for how long the smallest droplets remain airborne and how many there are. where the researchers write.

Careful estimations

The researchers described the droplets using two exponential decay functions, with the top 25% in scattering brightness and the dimmer 75% fraction having exponential decay constants of 8 min and 14 min, respectively.

They used the weighted average decay rate of all droplets to calculate the terminal velocity of the droplets and, given smaller droplets fall at a slower rate (staying airborne for longer), from the velocity they were able to estimate the average fallen droplet size.

The probability a droplet contains a viral particle depends on the initial droplet volume, but evaporation causes a rapid decrease in volume after release from the mouth. The team made shrinkage assumptions based on the relative humidity and temperature of the experimental settings, estimating the initial droplet size to be 12-21 micron in diameter.

The researchers were unavailable for comment, but the NIDDK responded to questions on their behalf. The NIDDK told Physics World that the researchers were “surprised to find the enormous number of particles in the 12-20 micron range [as this was far higher than suggested by previous research] that, after drying out and shrinking to about 4 micron, remain airborne for many minutes”.

Finally, to determine the probability a droplet encapsulates at least one virus, the team estimated the total volume of emitted saliva in their experiments, and combined this with data from recent research that shows saliva from a COVID-19 patient contains on average about seven million virus particles per millilitre.

They found that a second of speaking could be expected to generate 17-90 virion-containing droplets.

Substantial probability of transmission

In their latest paper the authors conclude, “These observations confirm that there is a substantial probability that normal speaking causes airborne virus transmission in confined environments.”

Julian Tang, a virologist at the University of Leicester, UK, who has expertise in respiratory viruses and their transmission, comments that this work is a “nice visualization method”. But points out that it would be “even more powerful” if the researchers combined their expertise with other disciplines to quantify live virus transported by speech droplets from COVID-19 infected volunteers.

The NIDDK says that Anfinrud and Bax’s team are building a third-generation laser-scattering apparatus to further address questions regarding speech droplet transmission.