Opinion

How can any scientists stand by this government now?

The Cummings saga has made it plain that scientific advisers are shielding the government’s collapsing reputation on coronavirus

by Richard Horton• Richard Horton is a doctor and edits the Lancet

Dominic Cummings predicted the events that have threatened both him and the government he serves. Writing on his blog in 2014, in an essay he called The Hollow Men, Cummings said: “The people at the apex of political power (elected and unelected) are far from the best people in the world in terms of goals, intelligence, ethics, or competence … No 10 will continue to hurtle from crisis to crisis with no priorities and no understanding of how to get things done … the media will continue obsessing on the new rather than the important, and the public will continue to fume with rage.”

Indeed, the public’s rage against Cummings, Boris Johnson and the prime minister’s lapdog cabinet seems to be growing day by day. The government’s goals, intelligence, ethics and competence are all under scrutiny and have been found wanting. Yet a cordon sanitaire has been placed around Cummings. He must be protected at all costs.

As Laura Spinney argues in Pale Rider, her history of the 1918 influenza pandemic and how it changed the world, getting the public to comply with disease-containment strategies means that each of us has to “place the interests of the collective over those of the individual”. In democracies, this is a hard ask. A central authority must temporarily suspend the cherished rights of individuals. And this demand carries dangers “if the authority abuses the measures placed at its disposal”.

Cummings certainly abused his authority as the prime minister’s chief political adviser. Matt Hancock, the health secretary, had given an instruction to “stay at home”. It wasn’t a guideline. It wasn’t advice. It wasn’t a suggestion. Hancock made clear that it was an instruction. Cummings violated that instruction. That violation has demonstrably undermined a carefully crafted public health message.

As long as Cummings remains in his position, the public can have no confidence that this government is putting their collective interests above those of a few privileged individuals at the heart of power. Johnson looks startlingly unable to understand the sacrifices made by families up and down the country he leads. Those families at the very least deserved an apology from Cummings. To dismiss their anguish reveals a man astonishingly detached from reality.

This sad episode also shows a regime that has lost its moral compass. And by regime, I don’t only mean politicians and their special advisers. I mean the regime of doctors and scientists shoring up this dysfunctional government.

Every day, government scientific advisers stand next to increasingly discredited politicians, acting as protective professional shields to prop up the collapsing reputations of ministers. Why did Yvonne Doyle from Public Health England agree to stand next to Johnson when he was defending Cummings on Sunday? Why did John Newton, who leads the UK government’s Covid-19 testing programme, stand next to Matt Hancock as the secretary of state for health and social care again sought to defend the indefensible?

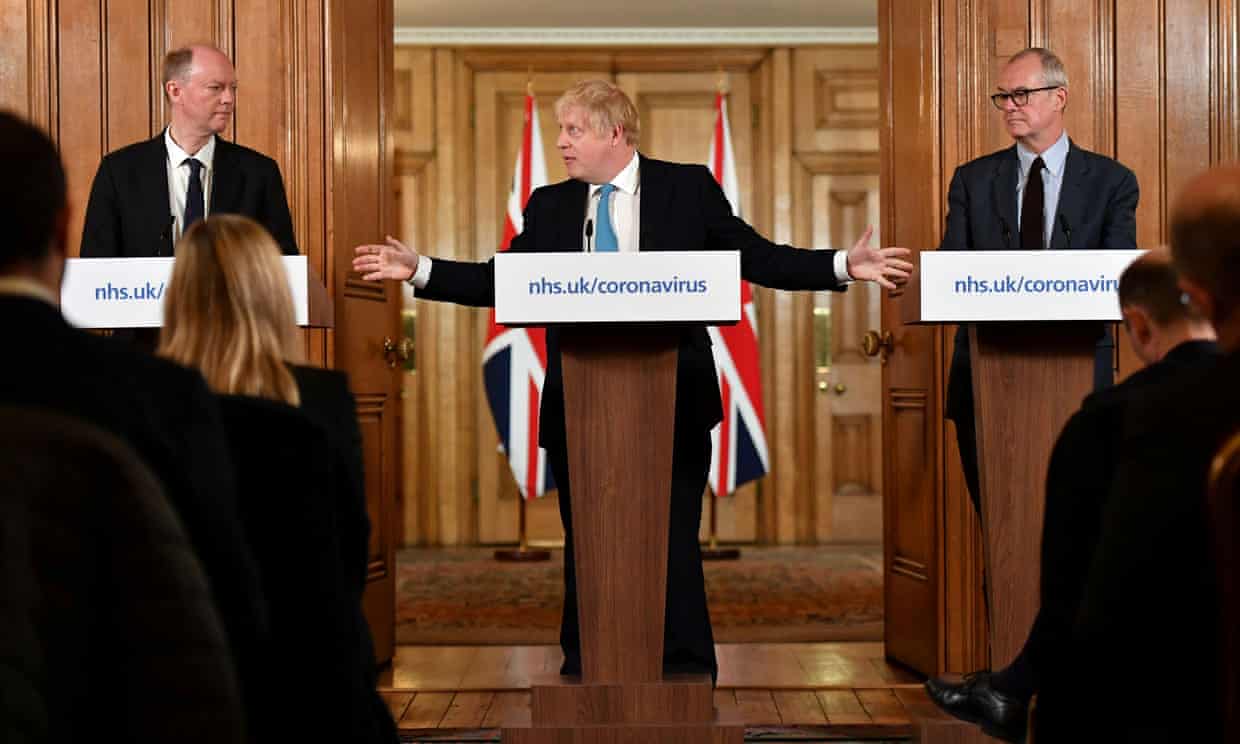

Every day a cast of experts – led by the chief scientific adviser, Sir Patrick Vallance, and the chief medical officer, Chris Whitty – lends credibility to this government by annealing their reputations with those of ministers. This fusion of character works when we believe the collective interest is being put first. But when the government places the instincts of an individual above the tragedies of a people, it is surely time to step away. Tying the reputation of advisers to a government that is now an international laughing stock seems a mistake. It cannot be a coincidence that Vallance and Whitty have not been seen for a few days. But even so, government scientific and medical advisers should now disengage from these daily briefings immediately and completely.

The failures within the scientific and medical establishment do not end with government experts. The UK is fortunate to have an array of scientific and medical institutions that promote and protect the quality of science and medicine in this country – royal colleges, the Academy of Medical Sciences and the Royal Society. Their presidents have been elected to defend and advance the reputation of medicine and medical science. And yet they have failed to criticise government policy. Why? Surely their silence amounts to complicity.

The relationship between scientists and ministers has become dangerously collusive. Scientists and politicians appear to have agreed to act together in order to protect a failing government. When advisers are asked questions, they speak with one voice in support of government policy. They never deviate from the political scripts.

Why was PPE not reaching frontline health workers? Instead of saying honestly that proper planning had not taken place, the adviser said the government was doing its best. Why was testing capacity so poor? Instead of saying honestly that the government had ignored the World Health Organization’s recommendation to “test, test, test”, the adviser said that testing wasn’t appropriate for the UK. Why did the government stop reporting mortality figures for the UK and other countries? Instead of saying honestly that the government found those figures embarrassing, the adviser said that such comparisons were spurious. Advisers have become the public relations wing of a government that has betrayed its people.

What is at stake here is not the fate of one political adviser or even of a government in crisis. It is the independence and credibility of science and medicine. Whitty and Vallance must now practise their own version of physical distancing – a distancing from a government that cares not one bit for the sacrifices made by its people.

In Pale Rider, Spinney warns us: “At some point … the group identity splinters, and people revert to identifying as individuals. It may be at this point – once the worst is over, and life is returning to normal – that truly ‘bad’ behaviour is most likely to emerge.” It is indeed at this point that the “hollow men” have appeared. It’s time to cut them loose.

• Richard Horton is a doctor and edits the Lancet