Stone Roses

Spike Island at 30: the Stone Roses gig was scary, shambolic – and pure bliss

It was an outdoor show that would enter indie folklore, a milestone night in British music history. One fan looks back on Madchester’s ultimate messy party

by David BarnettHistory tells me that the Stone Roses at Spike Island was, in musical terms, awful: the band seemed bored, the sound was weak. Here were 27,000 people crammed into a field surrounded by the chemical factories of Widnes to watch one of the most all-advised, badly organised and shambolic gigs ever held. My memory tells me something different. I was 20 in 1990, and had been working for a year as a trainee reporter at the Chorley Guardian in Lancashire. My relationship with the Stone Roses had begun the year before, when I found a loose cassette tape of their self-titled album under the seat of a train from Manchester to Wigan.

I hadn’t heard of them: at the time, my tastes ran to the jangling indie-rock of the C86 movement. The Stone Roses fed my hunger for that, but also opened the door to the Madchester scene that saw the exhilarating collision of indie pop and house music. When the Roses announced a massive outdoor gig – after shows in Blackpool and at Alexandra Palace that had become the stuff of legend – there was no way I going to miss it.

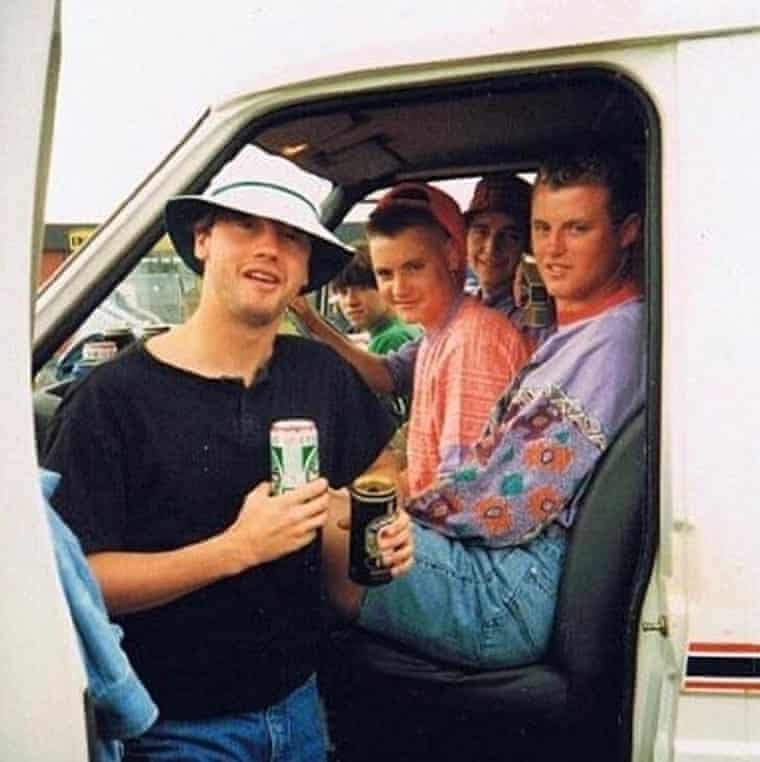

The weekend of the gig a colleague and I borrowed a van from our place of work, emblazoned with the paper’s masthead. I think we said we were going to cover a flower show, or maybe a non-league football game. We loaded up with mates and booze and set off for Cheshire. I’d been to Reading and Glastonbury so I thought I knew what to expect. I couldn’t have been more wrong. Spike Island was like Glastonbury, had it been organised on the back of a fag packet by half a dozen stoners in a beer garden.

High metal fences gave it the feel of a high-security prison (this was 12 years before Glastonbury installed theirs). It seemed impenetrable, even for those with tickets. Nobody seemed to know how you got in. Every entrepreneur in the north was selling hooky T-shirts, posters and hats. Inside was a sea of bucket hats and fake designer labels. Everybody was off their head. There weren’t enough toilets, nor enough drink, nor enough space. There was an aura of menace. At Glastonbury, amid the shiny happy people and middle-class kids dropped off by their parents, there were always knots of shirtless lads who seemed half a pill away from getting violent. That Sunday afternoon, it seemed they constituted the entire population of Spike Island.

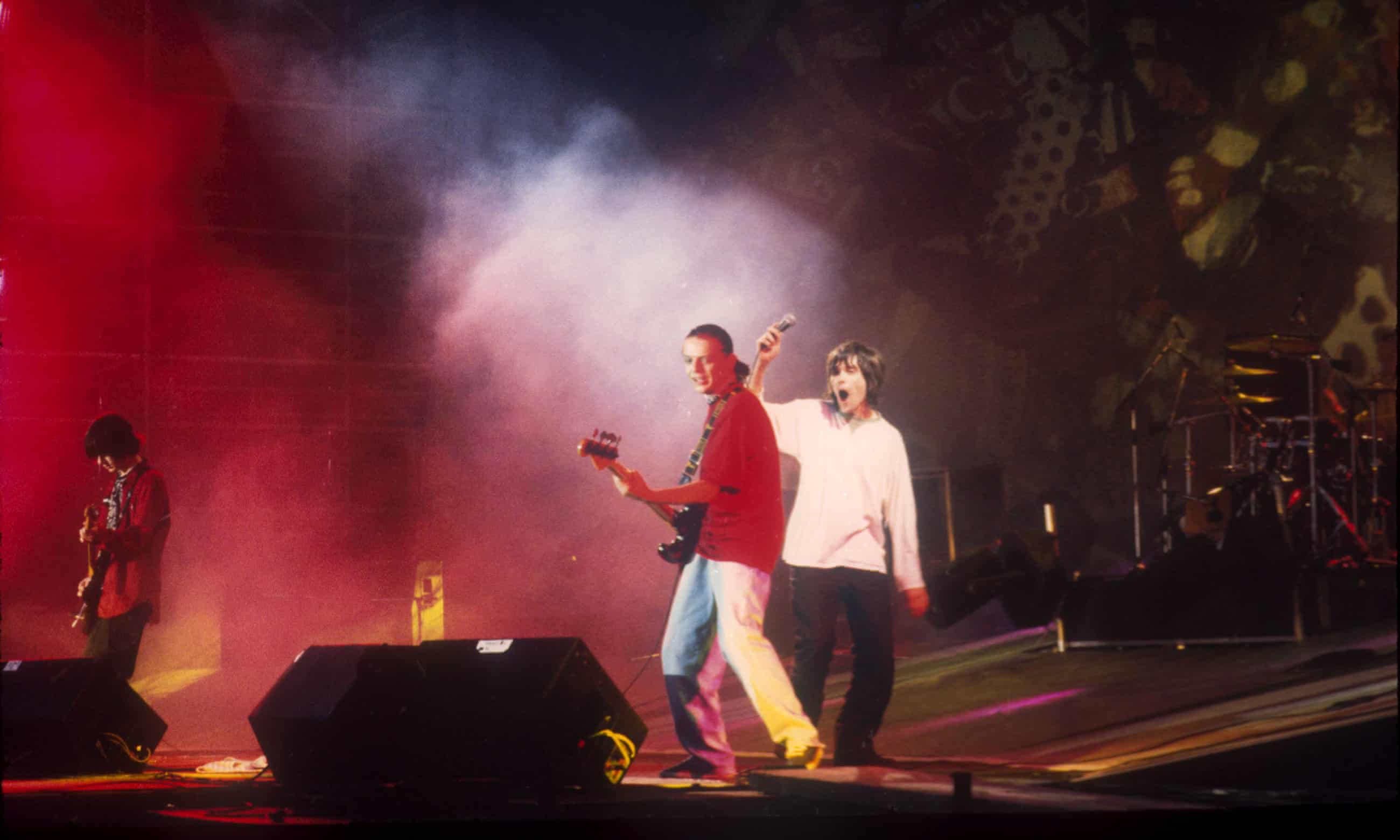

But then the music started: DJs Dave Haslam, Paul Oakenfold and Frankie Bones; MC Tunes, Madchester’s court jester, was there seemingly only to play his lone hit, The Only Rhyme That Bites, over and over. By the time the Stone Roses came on after sunset, people were climbing on the sound towers and dancing anywhere they could find a square of space. For some reason, Ian Brown was holding a huge inflatable globe. The sound was appalling and their performance was messy. And yet nobody cared.

Driving home in the Chorley Guardian van, somebody said: “Well, that’s the 80s over.” It felt true. The old regimes across Europe and the Baltic states were collapsing and Germany was reunifying. Thatcher went six months later. That hope wouldn’t last, although Spike Island’s reputation as a terrible gig did, calcifying into history.

Thirty years on, that seems to be changing: my 15-year-old daughter has never been more impressed with me than when I told her I was at Spike Island. The gig has achieved Woodstock levels of myth for some of her generation.

Perhaps today’s nostalgia for Spike Island also lies in the impossibility of attending any gig now or for the foreseeable future. From where we’re standing, dancing on urine-soaked ground to a band that feel like they’re playing half a mile away sounds pretty good.