Covid-19 Blows a $400 Billion Hole in Global Energy

Investment in oil and gas supply is in retreat, creating an opportunity to do things differently in the recovery.

by Liam DenningCovid-19 has blown a $400 billion hole in global energy. How we fix it will determine our success or failure versus that other implacable force of nature: climate change.

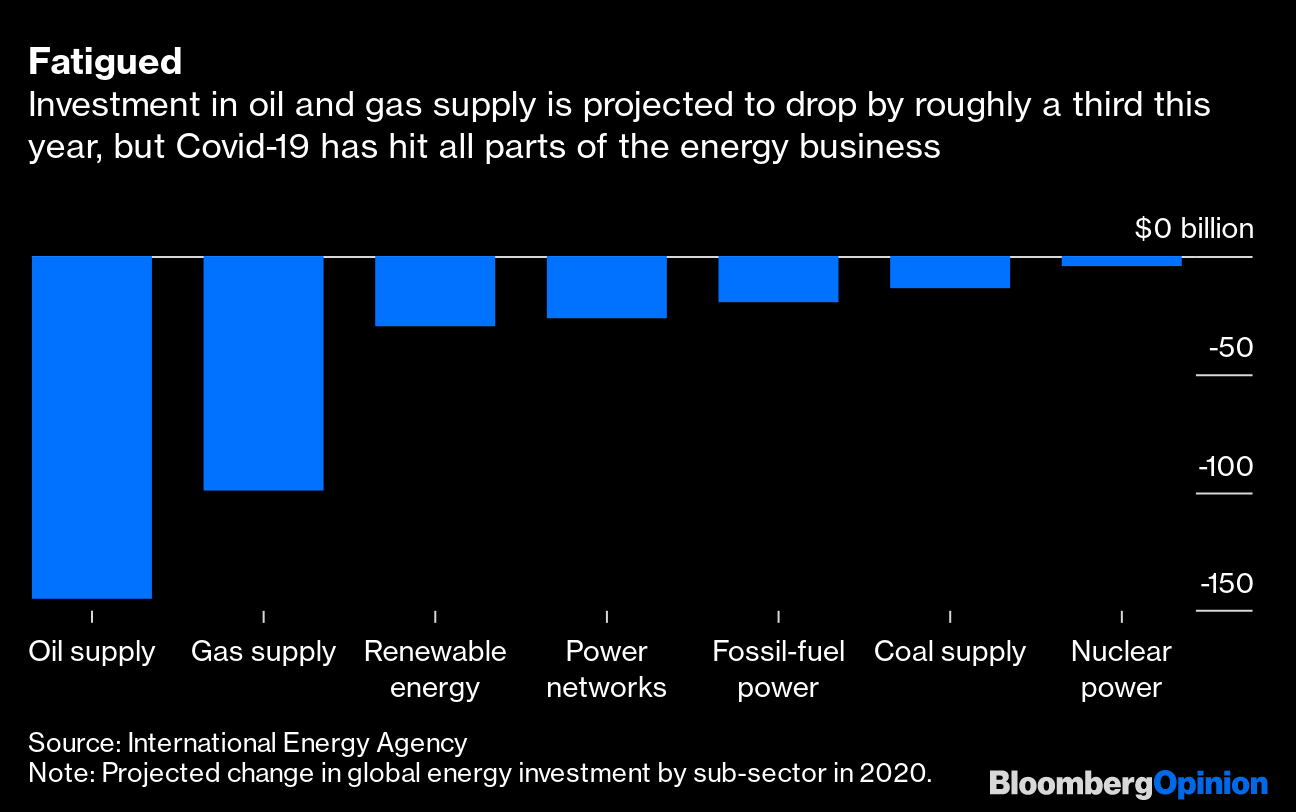

The International Energy Agency’s latest investment review, released Wednesday, could easily be subtitled: Don’t let a good crisis go to waste. That figure of $400 billion or so is the difference between where the IEA’s projection for energy investment in 2020 began the year — 2% growth — and where it now thinks it will land: a 20% decline. To put that figure in perspective, it’s not far short of all the money that went into the oil and gas production business last year. Which is apt, since that’s been hit hardest:

One of Covid-19’s secondary victims is mobility, so oil consumption has plunged. Even so, IEA head Fatih Birol poured cold water on the notion that peak oil demand may have happened already. Speaking with Bloomberg News ahead of the report’s release, he said:

In the absence of strong government policies, a sustained economic recovery and low oil prices are likely to take global oil demand back to where it was, and beyond.

It’s fairly easy to take issue with this prediction. We are barely months into possibly the most consequential economic dislocation the world has seen in many decades and possibly only months away from another round of it.

On the other hand, I don’t read Birol’s statement as a prediction; more of a warning. The key phrase there concerns “strong government policies.” Covid-19 raises the issue of agency with devastating clarity; faced with an alarming risk, what do we choose to do?

Oil demand may suffer long-lasting scars from changes in behavior or sheer economic trauma, but it is rising again off the bottom. The IEA raises the specter of 9 million barrels a day of day of missing supply in 2025 if investment doesn’t increase from here, perhaps touching off another round of high prices for a global economy that may be just getting over the pandemic.

This looks extreme; price signals wouldn’t stay dormant for that long. Yet it ought to serve its rhetorical purpose, prodding us to consider, collectively, why we wouldn’t try to do things differently.

For all the damage inflicted on fossil-fuel producers, incumbency remains a potent force. Quite apart from the petro-states whose existence rests to a large degree on oil’s indefinite prosperity, consider the downstream parts of the business. Last year saw a record amount of new liquefied natural gas capacity approved. Meanwhile, 2.2 million barrels a day of refining capacity was switched on last year — more than double the increase in demand — and another 6 million is due by 2025; too much even in an alternate, non-Covid-19 reality. Steel in the ground tends to create realities of its own. Like the oil supply currently, and reluctantly, being held off the market today, the underutilized plants of tomorrow will seek any opportunity to push cheap molecules into the market whenever they can.

There is no good reason why, when that $400 billion or so of investment comes back, it must be spent according to old patterns embedding chronic conditions of boom-and-bust, geopolitical tremors and, of course, runaway climate change. A striking finding in the IEA report is that spending on electricity services will outpace spending on oil products this year for the first time this century (and quite possibly ever). The fact it’s happening in a plague year means this isn’t a turning point, but it does emphasize the scale of the power business — and the scope for investment.

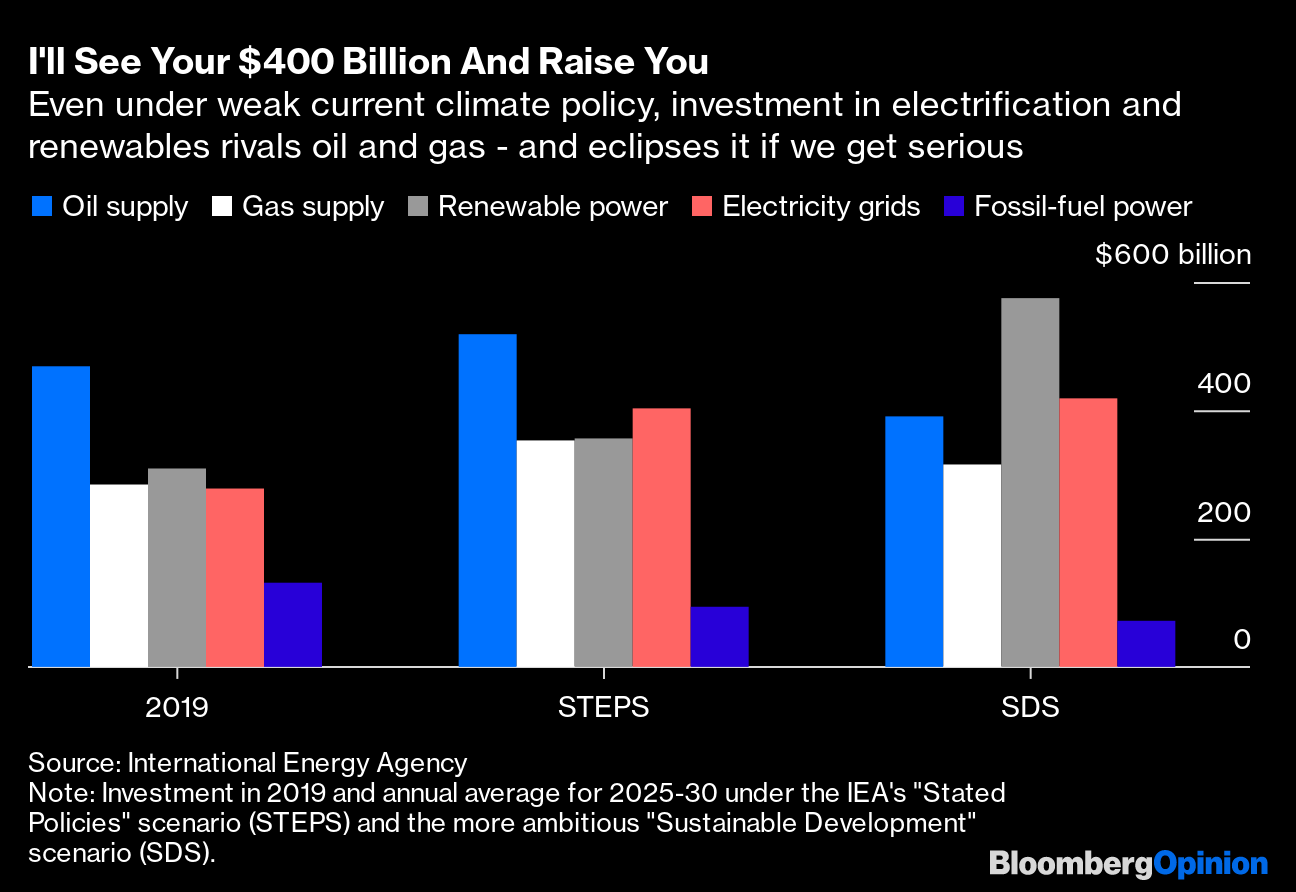

The IEA’s long-term scenario under current government mandates is known as “Stated Policies,” or STEPS. The more ambitious one, moving the world closer to Paris Agreement goals — albeit with too much reliance on carbon capture after 2050 — is called “Sustainable Development,” or SDS. Scenarios entail spending, and even under the weaker policy environment, the IEA projects investment in renewables to top that of gas supply. Under SDS, it soars past both gas and oil. Taken together, investment in renewables and power networks would average almost $1 trillion a year globally in the back half of the decade, a jump of 69% versus 2019. Oil and gas, meanwhile, rise by just 16% under the more favorable scenario and drop 7% under the climate-friendlier one, with oil dropping 17% within that.

A trillion a year, especially in the context of changes in policy, will sound like big government run amok to some. But check your priors. Investment in oil and gas supply was already about $750 billion last year, and that was down from mid-decade levels. Renewables and electrification projects also should create more jobs and lend themselves to more rapid deployment; think “move fast and fix things.”

Meanwhile, despite the prevailing wisdom, governments play a much bigger direct role in fossil fuels than in renewables. The share of government or state-owned enterprises in oil and gas supply or fossil-fuel power generation investment is about 40%-50%, according to the IEA, versus roughly 15% for renewable energy and efficiency projects. What, did you actually think Saudi Aramco is a private company now?

Yes, there are renewable portfolio standards and other policies that encourage more solar and wind power, but those exist because collective myopia has allowed incumbent fossil-fuel interests to lobby successfully against more transparent pricing of carbon. Yet even with that hindrance, the rapid drop in renewable-energy costs means a dollar spent on those technologies last year bought 50% more capacity than it did in 2012. Imagine the gains possible if market signals were aimed squarely at addressing climate change. If we are going to spend trillions powering our post-Covid societies anyway, why not optimize it for good outcomes?

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

To contact the author of this story:

Liam Denning at ldenning1@bloomberg.net

To contact the editor responsible for this story:

Mark Gongloff at mgongloff1@bloomberg.net