Kiki’s Delivery Service Is a Perfect Fable for Lonely City Dwellers

by Jackson McHenryFriday Night Movie Club

Spend an evening with Vulture, every Friday at 7 p.m. ET on Twitter.

Every week for the foreseeable future, Vulture will be selecting one film to watch as part of our Friday Night Movie Club. This week’s selection comes from staff writer Jackson McHenry, who will begin his screening of Kiki’s Delivery Service on May 29 at 7 p.m. ET. Head to Vulture’s Twitter to catch his live commentary, and look ahead at next week’s movie here.

So much of what happens in Kiki’s Delivery Service goes unexplained. There’s plenty we can hand wave away as the result of magic — witches exist, they fly on broomsticks, and talk to cats; sure, I believe it — but what’s genuinely mystifying about the movie is all the weird, essentially human stuff that takes place on the ground. Hayao Miyazaki’s 1989 animated movie, available to stream for the first time with the launch of HBO Max and which you should watch along with us on Friday, May 29 at 7 p.m. E.T., is one of the best movies about the mundane and frightening experience of growing up lonely.

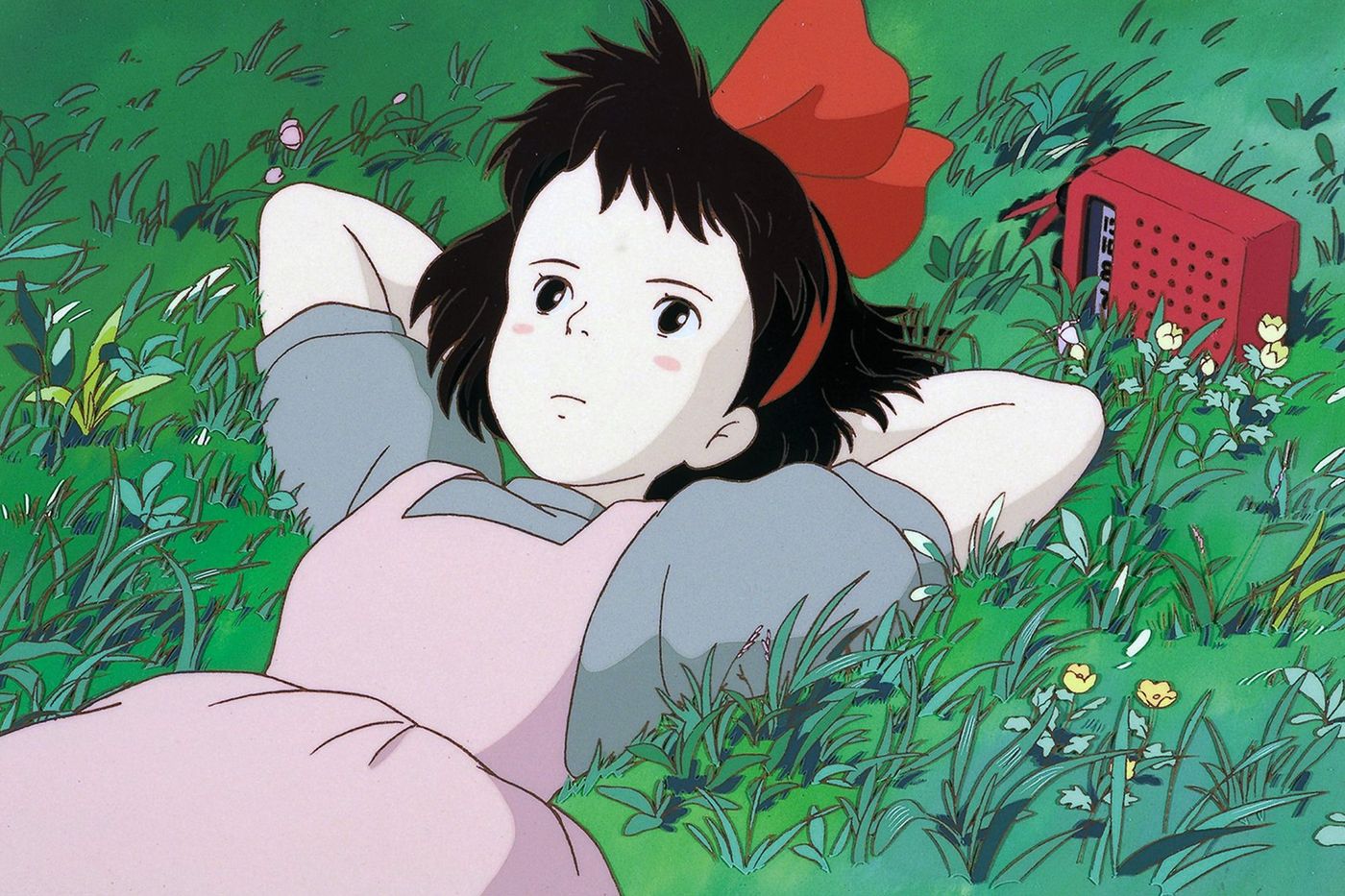

Kiki, a 13-year-old witch with a cat named Jiji for a best friend, sets off at the start of the movie — as all 13-year-old witches apparently must — in search of her calling and a town of her own. She lands in a beautiful, seaside, European-ish city, and sets up a delivery service, flying (or often just bouncing, as Kiki’s still mastering the whole flight thing) from house to house delivering bread. Kiki’s Delivery service becomes a series of vignettes about life and the people in the city, all accompanied by Joe Hisaishi’s gorgeous, lilting score.

There’s a pregnant baker and her burly, supportive husband. A sorta-sapphic painter who lives a deeply aspirational life in the forest. An aeronautics nerd who’s obsessed with flight and wants to be more than Kiki’s friend. We meet everyone glancingly, and yet understand something deep about them, the way it feels to collide, for a moment, with someone else’s life in the course of living in close quarters. In my favorite vignette, Kiki effortfully helps cook and deliver a Great British Bake Off–level fish pie, ordered by an older woman for her snooty granddaughter, who turns up her nose at having to receive yet another baked good she doesn’t want. It tells you so much about both the grandmother’s and granddaughter’s lives, and how unknowingly cruel people can be, that it sends Kiki into a deep depression. Some people are the worst, while some are much better than they need to be is as close as the movie gets to an overarching message.

What makes Kiki’s Delivery Service all the more poignant is that Kiki has to learn most of these lessons alone. Kiki has some help from Jiji, though Jiji is usually more interested in snarking and being a cat (depending on whether you watch the original version where Rei Sakuma does Jiji’s voice, or the English dub where Phil Hartman gives Jiji more of an attitude, the cat’s personality is very different). Arriving in the city alone, with zero help from her family, because that’s just how witches do things, she only slowly learns how to make friends and trust people. Even though there is a big action setpiece at the end, there’s never a point in the movie where everything suddenly clicks for Kiki. In its vision of growing up, everything remains hard, but eventually, you meet a few good people and figure out how to cope.

If you haven’t watched many Miyazaki movies before, consider Kiki a good entrypoint into his world, which you should definitely keep exploring now that his and the rest of Studio Ghibli’s works are finally streaming. Many, like this and Spirited Away, Nausicaä, Ponyo, and others, are about a young woman coming into her own, and Miyazaki has his specific fascinations with flight (watching Kiki fly will make you feel like you’re soaring along the seaside yourself) and the value of personal industry (watching Kiki clean her room will make you want to clean your room). Kiki falls earlier in the studio’s output — after the emotional whiplash-inducing sad-happy double feature of Grave of the Fireflies and My Neighbor Totoro — and it exemplifies so much of what it would become known for. More so than most children’s animated movies, these are all films that are meant to make you feel many things simultaneously, and often inexplicably.

In some ways, Kiki has less magic than most of Miyazaki’s films (there are no supernatural spirits, for instance), and yet it leaves much of its world up to your own interpretation. Midway through, Kiki loses her ability to fly, and stops hearing Jiji — maybe because she’s gotten older, maybe because she has a sort of writer’s block, maybe because she’s just depressed. Watching as a kid, I loved Kiki’s goofy physical comedy. Seeing it with my friends around our high-school graduation, I remember thinking about how we were all soon going to take off away from each other. Revisiting it for this series, I kept thinking about Kiki working in a pandemic, traveling from home to home making deliveries like so many people are now risking their lives doing. Even though it’s a rose-tinted fantasy, the story emphasizes her in-between position in city life — the way the people that tie us together are both taken for granted and relied upon, treated rudely and celebrated.

Kiki’s Delivery Service and the rest of the Studio Ghibli catalog are available to stream with a subscription to HBO Max.