Is American Airlines Worth Saving?

by Tim DunnSummary

- The U.S. airline industry is in the process of moving from payroll support grants which most carriers received to carrier-specific and optional loans from the U.S. Treasury.

- American Airlines has affirmed it will take CARES Act loans if their application is approved.

- Continued government investment in the deregulated U.S. airline industry raises policy considerations that will impact investor outcomes for American and the U.S. airline industry.

The airline industry and investors continue to try to adapt to the rapidly changing world left by the coronavirus and the governmental steps that were taken to contain it. From the suspension of travel from China on January 31, 2020, to March 11 and the order to suspend visitor travel from Europe to the weekend of March 13 when newscasts were filled with CDC briefings advising Americans to social distance and stay at home, the airline industry has been attempting to build new business plans for whatever may become the new normal. Just six months before the 9/11 anniversary, 3/11 will go down in airline industry history as yet another infamous date.

Parked American Airlines aircraft at Tulsa Source: Tulsa World

The U.S. government responded quickly to airline industry concerns about the lack of revenue that could permanently damage the airline industry. The $50 billion in financial support for U.S. airlines is part of the $125 billion in government support being offered to airlines worldwide. A number of airlines worldwide have already ceased flying or entered judicial reorganization.

Recent investor updates including from Southwest Airlines (LUV) show that LUV's operating revenue fell from 90-95% for April with very slight improvement to an 85-90% reduction for May which will mirror the revenue reduction for the June quarter. No airline is providing revenue or cash burn guidance beyond the current quarter, but the recovery is clear, even as some tout the doubling of traffic demand that is being seen at TSA checkpoints. Moving from a 95% to a 90% reduction is indeed laudable, but the size of the hole the airline industry is currently in cannot be underestimated.

As I noted in my most recent article on Seeking Alpha, the keys to survival for airlines depends on these four points:

- Adapt to the new business normal including about social distancing and increased cleanliness for those that do travel

- Obtain sufficient liquidity and cash to fund operations during the downturn

- Cut costs to be in line with revenues to reduce cash burn

- Be able to sustain the level of debt that each airline will take on as a result of this virus crisis

While I stated in my SA article why I believe Delta Air Lines (DAL) is executing the industry's best recovery plan, the reality is that not all airlines will be able to meet each of those four criteria for survival and success, even in the medium term. Now that the U.S. Treasury has put $25 billion into airline industry bank accounts via grants and partial loans for payroll support, it is time for investors and taxpayers to understand the next steps the industry faces, how the business models for airlines might change, and how investors might benefit from airlines that adapt better than others to the new realities of air travel.

Figuring out how the world has changed

In the midst of crisis, survival takes precedence. Once the prospect of immediately perishing is vanquished, a reassessment of life as a result of the crisis begins to take shape. Airlines will continue to be subject to medical advice regarding how the disease is spread (which continues to change), the steps necessary to limit the spread of disease, and guidance for community interaction.

Regardless of the outcome of COVID-19, the near global stay-at-home routine has caused many businesses to quickly pivot to teleworking and working from home could become part of the new normal for their businesses. Enormous parts of the global economy are at risk because of these changed work dynamics, including all aspects of the transportation, food service and hospitality, and real estate industries. Compound these changes which some companies will choose to embrace with the weaker economy and significant segments of the economy will face a much longer recovery and a bleaker future.

The democratization of air travel that accelerated over the past decade might unravel, esp. as the cost of providing disease-free travel increases its costs. Personal perception of space will likely be permanently changed; being told to remain distant from those whose disease status is not known will not be quickly unwound. Americans have always demanded some of the greatest amounts of personal space in the world and have generally had the resources to create space that is lacking in many cultures. Many Americans have been challenged to wear facial coverings in the interest of the common good, a concept that clashes with individualism and the group norms that are part of many societies. Airlines, esp. in the U.S., are at the pointed edge of yet another spear with which society has to wrestle.

Public policy considerations

The U.S. airline industry spent the majority of its nearly 100-year life under government regulation which limited market access and regulated fares. In 1978, the Civil Aeronautics Board was disbanded and the free market assumed responsibility for setting domestic airline capacity, route selections, and fares. Airline failures, mergers, and bankruptcies were plentiful during the first 22 years of domestic airline deregulation but 9/11 provided such a major jolt to the airline industry that the federal government stepped back into the industry. Grants were given to U.S. airlines for security enhancements while a loan program was established to help U.S. airlines access capital markets. In the ten years that followed 9/11, all of the largest legacy airlines took a trip through chapter 11 bankruptcy and reorganization. While the first 20 years of deregulation claimed such legendary airline names such as Eastern and Pan Am through business failures and liquidations, all of the remaining airlines at 9/11 that do not exist today were acquired through mergers or acquisitions in the ten years that followed 9/11.

While the U.S. airline industry is the product of dozens of mergers and acquisitions, the four largest U.S. airlines now control 80% of U.S. airline traffic; the largest legacy carriers American (AAL), Delta, and United (UAL) have been joined by Southwest, a low cost airline that only burst on the national scene during the deregulated era. It is unlikely that there is any way the big four carriers can combine or even acquire significant assets from each other or acquire any of the remaining half dozen smaller carriers which largely function in niche and/or regional roles.

Boeing's CEO, David Calhoun, put voice behind the fears of a U.S. airline failure in his interview on a national news show by responding affirmatively to a question whether he believed that a U.S. airline would fail. While some airlines privately objected to his comments and cited Boeing's own financial and strategic failures, the business world could not help but perform a quick mental game of airline musical chairs. In contrast, Delta's CEO commented after Boeing's CEO's comments that Delta does not believe any U.S. airline will "go out of business" in 2020. Seeking Alpha contributors and analysts are divided on the long-term prospects and structure of the airline industry.

The CARES Act followed the same principle that the Treasury Secretary provided to American business as a whole in the early days of the economic shutdown: viable businesses that lacked access to capital would be provided with the resources to remain in business, largely through loans. The U.S. airline industry received payroll support grants during the first phase of the CARES Act to be followed by loans for which all airlines can apply. Most U.S. airlines have made application for federal loans but they do not have to decide if they will accept them at this time; even those airlines that say they want the loans will know in the next weeks if the Federal government will extend loans to them.

With the prospect of tens of billions of dollars of taxpayer money at risk and with the possible distortion of the free markets, the question must be asked if we as a country want to rebuild the airline industry that existed pre-COVID-19 or if this isn't an ideal time to require significant structural changes in the industry. Further, the question must be asked if the U.S. has already saved the airline industry, even if not every carrier can be saved going forward. In order to answer those questions, we need to more deeply discuss how the U.S. airline industry does its job and how well the industry and specific carriers contribute to the national aviation system. The answers to these questions will have profound impacts on airline equity and bond investors.

While this article specifically addresses American Airlines, I believe the same principles apply if a minority number of airlines or U.S. airline capacity requires further federal financial assistance.

Is this what we want to rebuild?

There were only two major requirements that airlines had to comply with by accepting the first phase of the CARES Act which was based on summer 2019 payroll expenses for each airline. First, airlines have to maintain some level of service commensurate with what they operated in 2019 or planned to operate this summer; there have been numerous exemption requests from carriers for the minimum service requirements and most have been granted by the Dept. of Transportation. Second, airlines have to commit to not furloughing or laying off employees or cutting salaries but do have some ability to reduce the number of hours worked and paid. Several airlines have already stated that they will furlough personnel when they are permitted to do so in October. In addition, in response to early opposition to the amount of money that was spent on stock buybacks, airlines are prohibited from certain capital management practices including stock buybacks. Beyond these specific guidelines that are being equally applied to all carriers, there is broad discretion given to airlines regarding how they should restructure their business in order to survive.

Alaska, American, Delta, Hawaiian, and United are legacy airlines that engaged in interstate air transportation prior to 1978. They all operate hub and spoke route systems enabling them to distribute traffic from multiple cities across their networks through one or more hubs. American, Delta, and United are often called global airlines because they provide service on at least five continents as well as serve hundreds of small cities throughout the U.S. The legacy airlines have the most complex pricing model by offering multiple levels of service and pricing their product to target each type of customer, including fares offered by low cost and ultra-low-cost carriers. All other U.S. airlines cater to more narrowly defined customer bases without a focus on serving small cities, offering global networks, and using a variety of aircraft types to match supply with demand in different market types. It is impossible to know if less than three U.S. global/nationwide network airlines can adequately connect and serve America's transportation needs.

In determining how effective each type of airline and each specific airline is in achieving its mission of serving the public and investors, it is worth considering four key factors: depth and quality of service including level of fares, profitability, and investor returns.

In aggregate, the U.S. has one of the most enviable positions in global aviation and the system is very well-used. According to DOT data, there are 363 U.S. airports served by U.S. commercial airlines. Each of the AAL, DAL, and UAL networks served more than 200 cities as of the end of 2019, Allegiant (NASDAQ:ALGT) is the only carrier that served between 100 and 200 airports; all of the remaining U.S. airlines other than SkyWest (NASDAQ:SKYW) served less than 100 cities. DAL served the most cities with large jets (148) while SkyWest provided regional carrier service (typically aircraft less than 76 seats) to 255 cities, largely under contract to one of four larger legacy carriers.

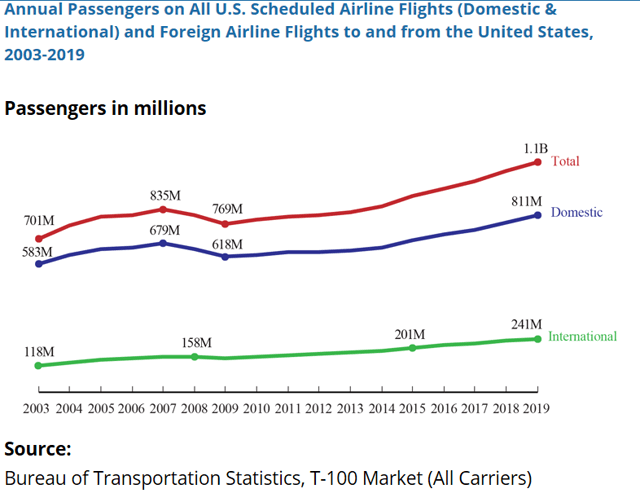

Nearly 1.1 billion passengers flew to, from or within the United States, meaning nearly every American, on average boarded three flights during 2019. Approximately three-fourths of passenger boardings were for domestic flights while, on average, the equivalent of nearly two-thirds of the U.S. population arrived or departed the U.S. on a U.S. or foreign carrier international flight.

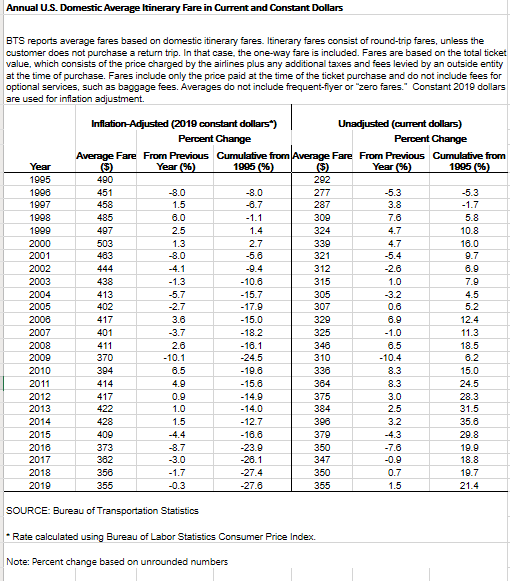

Airfares, both internationally and domestically, continued to fall in 2019 and are now 28% lower on an inflation adjusted basis since 1995.

The U.S. has built the world's most valuable air transportation system that is more affordable and is used by more people than ever, at least before the virus crisis.

The U.S. DOT has been tracking airline customer service metrics for years and, despite the general dislike of the airline industry, airline customer service in the United States is better than it has been since deregulation. There are, however, significant differences in how well specific airlines perform on DOT customer service metrics.

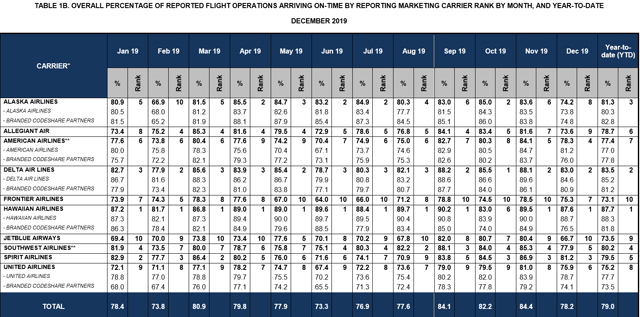

For 2019, 79% of U.S. domestic airline flights were on-time (within 15 minutes of scheduled arrival) with Delta and Southwest operating their networks at four and one points, respectively, above-average while, rounding out the four largest airlines, American and United both operated their networks at below average on-time.

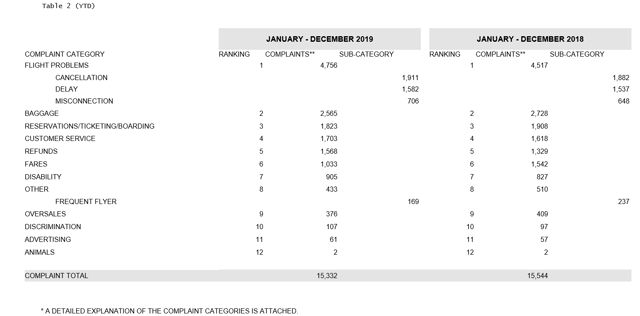

DOT Air Travel Consumer Report

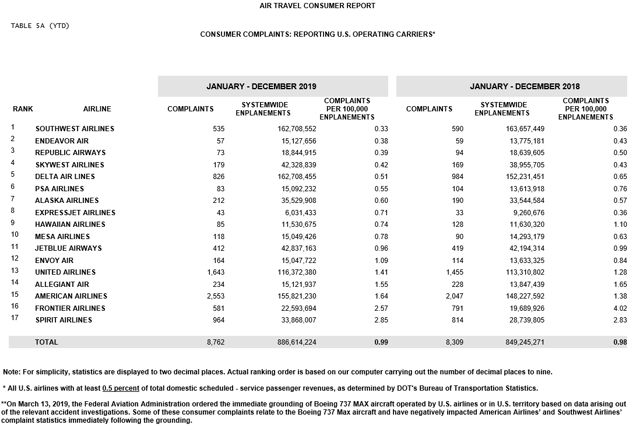

Across most of the DOT's metrics, Delta and Southwest operate above average on DOT metrics including baggage and wheelchair handling, cancellations, involuntary denied boardings, and consumer complaints while American and United operated below average.

There clearly is not a defined difference in the performance on DOT metrics based on the business model; Delta is a legacy/global carrier while Southwest is a low cost carrier. The only consistent connection between business model and DOT metrics is that the ultra low cost carriers such as Spirit (NYSE:SAVE) and Allegiant consistently perform worse than the industry in consumer complaints. The DOT measures the reasons for consumer complaints and their data shows that the largest reason for complaints is flight problems, which include delays, cancellations, and misconnection. The second highest complaint category is customer service; Southwest does particularly well in this category because of its ability to resolve problems when they occur. The legacy/network airlines operate more complex business models in part because they connect more passengers and baggage; in some cases, legacy carriers do not perform as well in delivering on their business model as low cost carriers which promise less but often deliver much more what consumers want. However, Delta's complaint ratio is about one-third of American and United's indicating that execution rather than complexity of the business model is a more significant factor.

DOT Air Travel Consumer Report

Profitability is and should be a key metric to determine the level of success for U.S. airlines. It is not a surprise that Delta and Southwest, which lead the industry in most of the DOT's consumer metrics, also lead the industry in profitability; Southwest's net income (NI) margin for 2019 was 10.2% while Delta's was 10.1%. Spirit and Alaska posted NI margins in the 8.7% range for 2019 while JetBlue and UAL posted 7.0% NI margins. American brought up the rear of the industry with a 3.7% net income margin for 2019. Once again, business model is not necessarily indicative of profitability.

The DOT measures profitability of airlines in each of three international regions in addition to the domestic market. The largest global region for U.S. airline profits was in Latin America; American, which is by far the largest carrier in the region, accounted for two-thirds of the profits. Most U.S. airlines serve Latin America since the same type of domestic aircraft can be used to serve much of Latin America. In contrast to Latin America, American reported that both its transatlantic and transpacific route systems did not make money. Delta reported the largest profits in the transatlantic region while United, the largest airline across the Pacific, said it was unprofitable in transpacific service. Delta is the only U.S. airline that reported profits in all three global regions as well as the domestic market.

The domestic market has clearly been the most profitable for U.S. airlines and its recovery will be the fastest based on most airline executive comments. The Pacific has been the least profitable global region while the Latin America region is the global region served by the most carriers and is the most profitable for the US industry as a whole even though the transatlantic region generated more revenue in 2019. Based on revenues, the Latin America region is about 10% of the size of the domestic region and slightly larger than the Pacific region which is itself 60% of the size of the Atlantic region. The Pacific region has not been profitable on an aggregate basis for U.S. airlines for three years as of the end of 2019.

Current Big Four Airline Financial Positions

Several airline metrics have been closely watched since the virus crisis began: cash on hand, access to capital markets, unencumbered assets, and cash burn rate.

Cash burn includes passenger refunds for tickets that were not used and were as high as $100 million/day according to DAL. Most airlines expect their cash burn to drop to half or more of their highest levels. Based on carrier estimates, American expects to have a cash burn rate of $70 million/day for much of the second quarter, dropping to $50 million/day while Delta and United expect to be at about $40 million/day and Southwest expects to be in "the low $20 million/day." Other than American, most carriers June quarter cash burn rate is roughly equal and proportional to their pre-virus crisis expenses. Several airlines have recently said they are not burning cash on select days.

Delta and Southwest indicate that they will have approximately $12 billion plus in cash on hand as of June 30. United says it had nearly $10 billion on hand at the end of April which could fall by several billion dollars by June. American said it had nearly $7 billion as of March 31. Smaller carriers have proportionate cash levels. American is guiding to approximately $11 billion in cash at the end of June although that estimate includes $4.8 billion in proceeds from the second phase of the CARES Act loans.

Delta and Southwest have each raised more than $10 billion in the capital markets since the beginning of the year. Southwest's total includes approximately $2 billion in equity while Delta's total is all debt. American and United have raised considerably less with UAL raising equity but scrubbing a recent debt offering while AAL raised $2 billion in debt in the first quarter.

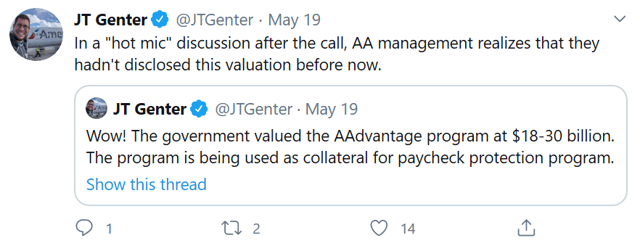

Finally, the value of unencumbered assets is key to how much capital each carrier can raise whether from the federal government or from private lenders since the Treasury has required that airlines pledge collateral, even for the loan portion (approximately 30%) of total phase one CARES Act financing. Delta and Southwest recently provided updated information on the value of their unencumbered assets and each stated they have about $6-7 billion in remaining unencumbered assets excluding their loyalty programs. United did not provide updates on the value of their remaining unencumbered assets but United's debt deal failed in part because it offered hundreds of aircraft, some of which are older, indicating that they probably have limited amounts of high-value collateral remaining. American's previous statements indicate that it has limited remaining aircraft collateral which means its remaining collateral would have to include airport slots, spare parts, and its loyalty program - but it is unclear how much of those types of collateral is available to them. American did recently indicate, perhaps for the first time, that it offered its AAdvantage loyalty program to the U.S. Treasury as collateral for its phase one CARES Act loans. This would indicate that American either has very little collateral remaining other than its loyalty program or is reserving that collateral for its phase two loan. Given the changing value of collateral, it is difficult to determine how much collateral any airline has remaining and how much of it can be used for private-sector or government loans.

Most carriers have said they applied for phase two loans but have not decided whether they will take them if approved. American has stated that it has a right to $4.75 billion in phase 2 CARES Act loans and will take those loans if their application is approved.

From a financial perspective, it appears that most airlines other than American and United can cut their costs to be able to align with new revenues, have sufficient cash or can raise additional liquidity in the capital markets, AND have sufficient collateral remaining to obtain financing from either the private capital markets or the Federal government.

While it is not entirely clear, United can probably cut its costs to align with new revenues but may not have sufficient collateral other than its loyalty program to pledge to private lenders or the U.S. Treasury. It is possible that United may be able to slow its cash burn rate such that it will not need further cash beyond what it will have on June 30. United has already announced early retirement and voluntary separation programs and has said furloughs and layoffs are likely after September 30.

American probably does not have sufficient cash on hand to fund its operations given its current cash burn, probably does not have sufficient remaining collateral other than its loyalty program available to offer any lender and probably cannot access the capital markets. The loyalty program for a large U.S. airline has never been the primary remaining collateral for a private or government loan, so it is uncertain what percentage of the value of a loyalty program could be accepted as collateral. American has apparently already pledged part of the value of its AAdvantage program.

source: JT Genter

Just as in the immediate post 9/11 bankruptcies, it is perhaps two legacy carriers that face a liquidity crisis while this time it appears that Delta can remain outside of bankruptcy and without government aid while American and/or United might need one or both.

There is not an industry-wide inability to control costs, access private capital markets, or apparent need for further government financial assistance even though it has been committed as part of the CARES Act.

Returning to our discussion about the structure of the airline industry, it is clear that the segments of the U.S. airline industry that are most at risk by a potential failure of American or a chapter 11 bankruptcy of American or United are long-haul international service and regional airline service to small and medium cities. There are multiple airlines that serve the mainline domestic and near international markets and most of the carriers serving those markets are not at risk of chapter 11 bankruptcy or shutdown.

American faces a potential collateral crisis. AAL is the only U.S. airline that needs additional capital to fund operating losses beyond the cash it has on hand or can raise. Their cash projections have included expected federal loan proceeds. AAL management has resisted suggesting that furloughs are necessary even though DAL and UAL have both already begun the process of reducing their staffing. LUV says that it might be forced to drop its practice of not furloughing. Yet, American, which has tens of thousands more employees than Delta or United, believes it can reduce costs without furloughs - but is counting on federal money to fund its continued operating losses. Chapter 11 has historically been a powerful force that airlines have used to reduce labor costs and yet, American, the most recent airline to have been in chapter 11, has had the industry's highest unit labor costs for most of the seven years it has been out of bankruptcy.

However, a chapter 11 bankruptcy requires debtor-in-possession financing. Given the level of remaining collateral that AAL has, it is doubtful that American has enough remaining collateral for DIP financing if AAL needed to file for chapter 11 and to pledge collateral for a federal loan. AAL's strategy appears to be to obtain a federal loan and get its costs down outside of bankruptcy even though it has been unable to do so during the best years of the industry and with the most recent trip through bankruptcy among U.S. airlines. If AAL has the collateral to obtain a loan under the CARES Act but not from private lenders, then the risk of bankruptcy appears to be the reason why AAL does not have access to private capital markets. It is not a given that the U.S. Treasury will assume risks that the private markets would not accept.

Before we consider the implications of chapter 7 and 11 bankruptcy reorganizations in the U.S. airline industry, it is worth looking back to the post 9/11 period and the U.S. government's financial involvement in the U.S. airline industry's recovery.

Remember the ATSB

The Air Transportation Stabilization Board was created less than two weeks after 9/11 to help inject liquidity into the airline industry and administered through the U.S. Dept. of Treasury. It was authorized to loan up to $10 billion to U.S. airlines but ended up making loans for 12% of that amount.

United was the largest airline that applied for but was denied an ATSB loan, ATSB saying that UAL could obtain financing from other sources. Denial of the ATSB loan led to UAL's chapter 11 bankruptcy which lasted for more than three years. The most notable aspect of United's chapter 11 reorganization is that it terminated all of its defined benefit pension plans and turned them over to the Pension Benefit Guarantee Corporation. United cut many cost categories including employee costs but emerged from bankruptcy, later to merge with Continental in 2010.

The ATSB approved loans for seven airlines but none of those airlines exist today in the form in which they were granted the loans.

America West, a Phoenix-based post-deregulation airline, was the largest airline that applied for and received a loan from the ATSB. It paid the loan off with interest and immediately engaged in a merger with the larger USAirways which was in bankruptcy for the second time post 9/11. Nearly five years later, USAirways followed the same tactic and pursued American during its chapter 11 filing, merging with the larger carrier upon AAL's exit from bankruptcy in 2011. Doug Parker, American's current CEO, began his career at American and worked at America West and USAirways where he was the CEO at the time USAirways presented a competing bid to AMR Corp's standalone plan of reorganization. USAirways failed at the same strategy of presenting an alternate plan of reorganization during Delta's chapter 11 reorganization.

American Airlines heritage jet Source: thestreet.com

The medium-term results from the ATSB show that United Airlines was able to find funding and restructure in chapter 11 where many U.S. airlines have spent time both before and after 9/11, often resulting in mergers using private capital. The America West ATSB loan, even though profitable for the U.S. Treasury, likely facilitated a merger with USAirways which would not have occurred had the U.S. government not injected capital into America West; United was just emerging from chapter 11 and Delta and Northwest were entering at the time of the America West-USAirways merger; the airline industry that did not receive government money was still recovering from 9/11. Most low cost carriers avoided bankruptcy and grew rapidly in the decade after 9/11 as legacy carriers reorganized their businesses.

Implications if American Airlines Fails

Many businesses have already failed as a result of the coronavirus lockdowns even with the trillions of dollars that the U.S. government has injected into the economy. Corporations will fail including others in the travel industry such as Hertz that did not receive government aid. Because the airline industry received not only direct grants but also now has access to federal loans, the discussion about the future of the airline industry is a public discussion with implications for airline investors.

The original basis for providing direct grants and loans to the U.S. airline industry was because airlines are considered essential to the U.S. economy and they needed to provide service during the lockdown as well as once the economy begins to recover. Grants were given to airlines so that they could retain and pay their workforces. There were ample indications that airlines could not access capital markets even though many had investment-grade credit ratings.

One of the justifications for arguing for support for airlines is that specific airlines are too big to fail; that statement requires examination. The economy of the U.S. was not directly harmed by the successive chapter 11 filings by most of the legacy carriers post 9/11 so a chapter 11 filing of one or more airlines now will not likely risk failure to the U.S. economy. There were no shutdowns of large U.S. airlines in the decade post 9/11 other than TWA which had been acquired by American prior to 9/11.

American is the largest U.S. airline by employment with over 130,000 employees including at its subsidiaries. Its largest employee bases are predominantly in the southern U.S. which has been less impacted by COVID-19. American froze all of its defined benefit pension plans in chapter 11; they would likely be terminated if American either files another chapter 11 or is liquidated. Chapter 11 filings typically result in downward pressure on other airline salaries. It is not as likely that other airlines' salaries would fall as much if AAL was liquidated. American's headquarters is in the Dallas/Ft. Worth metroplex which is also home to Southwest Airlines.

American operates hubs in multiple cities in the United States. The only metro areas where it has more than a 50% local market share and no competitor has at least 20% share is in Miami/Ft. Lauderdale, Charlotte, and Philadelphia. All three of these cities have sufficient local demand as well as facilities to support other carries should American fail. There are other carriers with large operations at the same airport or other airports in the regions of Chicago, Dallas/Ft. Worth, Los Angeles, New York City, Phoenix, and Washington D.C. which host American hubs. American has called its hubs at Charlotte, Dallas/Ft. Worth and Washington National as its most profitable; other airlines probably have low profitability.

American is the second-largest slot holder at NYC's LaGuardia airport and the third-largest at JFK. It is the largest slot holder at Washington National Airport. In the past, the FAA has relaxed slot controls and the DOJ has helped ensure increased competition via slot divestitures and creation of additional slots. AAL is one of the largest foreign slot holders at London Heathrow airport where it has a joint venture with British Airways, the largest carrier from the United Kingdom to the U.S. Slots at London Heathrow can be traded on commercial terms and routinely trade for more than $50 million per slot pair.

Airports in the United States are almost entirely locally owned but partially federally funded through user fees which are generally proportionally spread between the size of each airline's operations. The loss of a hub - which requires a disproportionate amount of airport real estate compared to the amount of local traffic - has happened when cities like Cincinnati, Cleveland, Memphis, Raleigh-Durham, and Pittsburgh have lost their hub status. In some cases, the airport consolidated remaining operations into newer facilities while others still have more gates than they need for their current level of air service, years after losing hub status. In most cases, former hubs have more low-cost airline service than they had as hubs and other carriers including other legacy carriers have added service which had been cut.

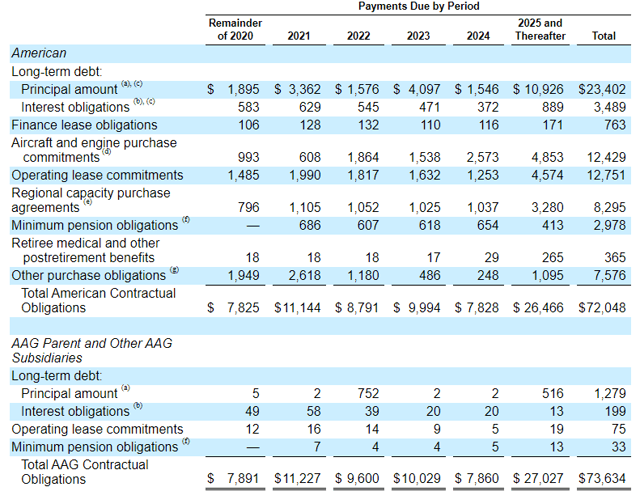

American operates one of the world's largest fleets of aircraft; it owns more than 500 mainline and 300 regional jet aircraft, nearly all of which have been pledged as collateral or do not have enough value to serve as collateral. AAL's annual interest expense is approximately $1 billion which could amount to more than 3% of AAL's operating revenue for 2020. Since most of American's current debt is aircraft-backed, it is doubtful that they can significantly reduce their debt without disposing of some of their aircraft, a process that is very hard to do outside of bankruptcy. American leases hundreds more aircraft from leasing companies that would be forced to place those aircraft with other lenders. If American failed after providing aircraft-related collateral to the U.S. Treasury, the responsibility of placing those aircraft could fall to the U.S. government which might also be involved in selling off parts of American's loyalty program which has also been pledged as collateral. If American files a chapter 11 reorganization, it would most likely reject leases on aircraft before attempting to dispose of owned aircraft. American has over $12 billion in commitments for aircraft-related purchases, mostly from Airbus and Boeing.

While American Airlines has a business which is capable of generating tens of billions of dollars in annual revenue, their strength markets are spread throughout in the U.S. such that other airlines can and will step in to provide air service where it is economically viable to do so if necessary. Again, this principle is true not just for American but just about every U.S. airline. The livelihoods of tens of thousands of American employees and retirees would likely never recover, assets would have to be redistributed to other airlines and that process could take years given the financial state of the airline industry. If a failure of American were to occur without further government intervention, most of the economic impact would be born by private investors and suppliers as well as American employees and retirees. If American filed chapter 11, some, but not all of its stakeholders would suffer complete loss while others could sustain partial losses.

It is also worth noting that the growth strategies that several airlines announced before the virus crisis would have increased chances of success if either American or United reduced service as part of a chapter 11 bankruptcy or a potential liquidation. JetBlue has stated that it intends to fly to Europe using long-range A321 aircraft from its bases in Boston and New York. JBLU, LUV and SAVE all have major operations at Ft. Lauderdale including with the potential to expand deeper into S. America. Delta is applying for a joint venture with Latam which is the largest foreign airline in Miami and serves many of the largest countries in S. America. American and United share the only remaining rival legacy same airport hubs at Chicago O'Hare.

American's market cap is currently $4.1 billion, less than one-fourth of the market cap of LUV.

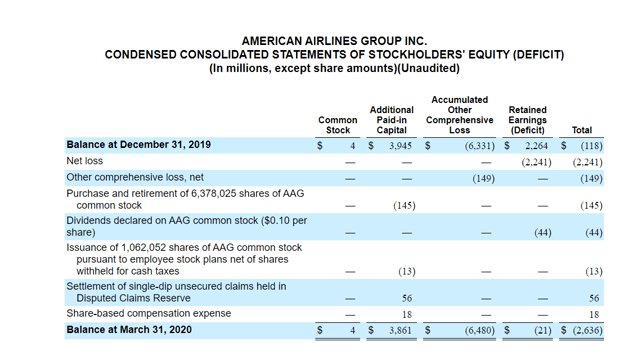

AAL's contractual obligations and stockholders' deficit are noted below.

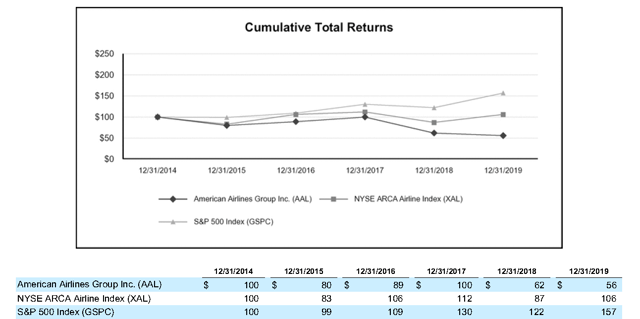

Note that AAL has underperformed the S&P 500 Index and the NYSE Arca Airline Index every year for the past five years.

source for all: AAL 10-Q March 31, 2020

Credit default swaps for AAL are currently roughly twice as expensive as they are for UAL, four times more expensive than for DAL, and ten times more expensive than for LUV.

Next Steps: U.S. Treasury

The CARES Act, just as with the ATSB, does not say that the federal government must provide financial support, including loans, to every airline; there are qualifying requirements including the ability to provide collateral. The U.S. Treasury will have to answer these questions as well as many others in determining the future of loans to American and any other airlines that choose to accept them:

Is a loan necessary to preserve the U.S. air transportation system as well as its current structure?

How long will this era of depressed revenue last and does each airline's business plan reflect the necessary adaptations to the new revenue environment?

Do carriers have sufficient collateral to secure a loan?

Can carriers that are applying for loans obtain capital in the private markets?

Will American (or any other airline) fail if the Treasury does not extend loans?

Did airlines that apply for loans have viable business models before the virus crisis?

Do carriers applying for loans have the ability to: support the debt levels they previously had in addition to new debt they will have to take on?

Will the remainder of the airline industry recover and will air service be maintained if a loan is not made to American (or any other airline)?

The U.S. Treasury has two options with various outcomes for AAL equity and bondholders:

- Approve the loan, believe that AAL can cut costs outside of bankruptcy, and the industry and AAL recover sufficiently to avoid bankruptcy. AAL would likely not improve its financial performance metrics relative to the industry, would have debt that far exceeds annual revenues, and would likely not reduce the size of its operations. The recovery of the rest of the industry would be delayed and/or limited. AAL equity and bondholders would be preserved.

- Deny the loan because the Treasury determines that AAL has sufficient collateral to obtain a private sector loan. The market, not the U.S. Treasury takes all future risks regarding American. AAL equity and bondholders would be preserved if AAL does not file chapter 11 or 7.

- Approve the loan, AAL later files for bankruptcy, and does not have sufficient collateral to support DIP financing as well as the federal loan. AAL could be liquidated. AAL equity and bondholders would potentially suffer complete loss.

- Deny the loan due to lack of a viable business plan which would result in chapter 11. AAL would then use the collateral earmarked for a loan to obtain DIP financing. Given the current low revenue environment, AAL would likely spend a protracted period in bankruptcy and would emerge smaller but not be eliminated. All AAL stakeholders would suffer some economic damage but far less than in a Chapter 7 liquidation. AAL equity holders would likely suffer a complete loss but the majority of debt holders would eventually recover losses if some AAL assets are placed with other airlines. Several AAL hubs would likely be cut in chapter 11 given that they have repeatedly highlighted the financial strength of some of their hubs but said others financially underperform. Based on history, competitors would likely grow in AAL markets during a chapter 11 filing.

- Deny the loan, AAL would file for Chapter 11 bankruptcy, exhaust its DIP financing during bankruptcy and be unable to successfully reorganize, and then liquidate. AAL equity and bondholders would potentially suffer complete loss but on a delayed basis.

American executives have said they expect a decision from the U.S. Treasury in the second quarter.

Disclosure: I am/we are long LUV, DAL. I wrote this article myself, and it expresses my own opinions. I am not receiving compensation for it (other than from Seeking Alpha). I have no business relationship with any company whose stock is mentioned in this article.