7 Pieces of Reading Advice From History’s Greatest Minds

If there’s one thing that unites philosophers, writers, politicians, and scientists across time and distance, it’s the belief that reading can broaden your worldview and strengthen your intellect better than just about any other activity. When it comes to choosing what to read and how to go about it, however, opinions start to diverge. From Virginia Woolf’s affinity for wandering secondhand bookstores to Theodore Roosevelt’s rejection of a definitive “best books” list, here are seven pieces of reading advice to help you build an impressive to-be-read (TBR) pile.

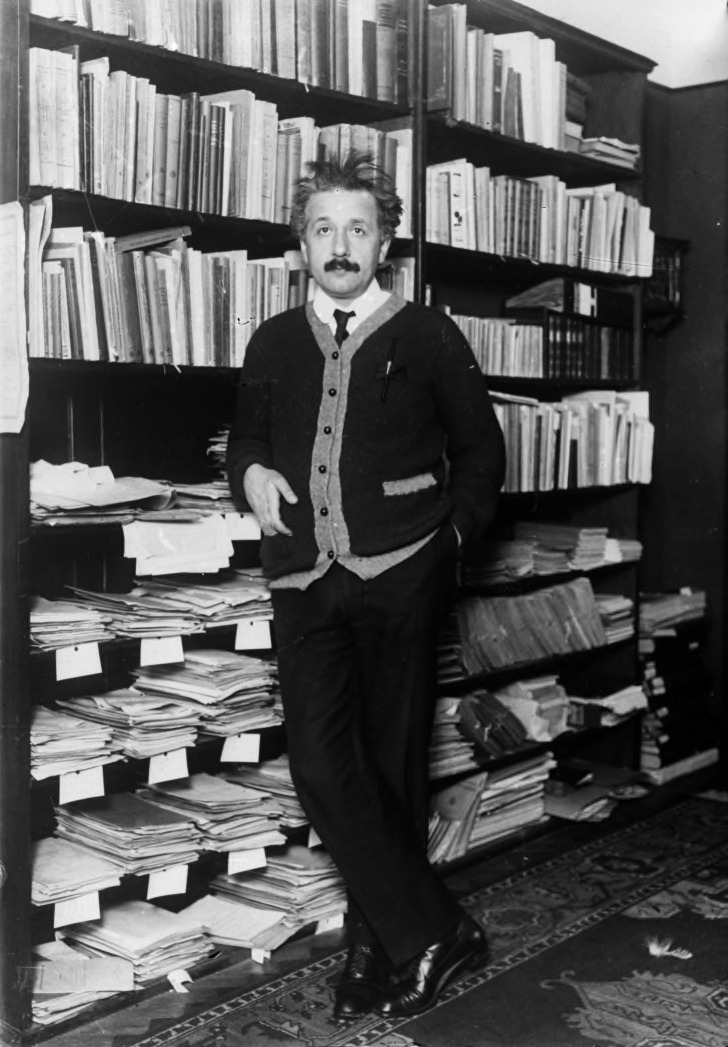

1. Read books from eras past // Albert Einstein

General Photographic Agency/Getty Images

Keeping up with current events and the latest buzz-worthy book from the bestseller list is no small feat, but Albert Einstein thought it was vital to leave some room for older works, too. Otherwise, you’d be “completely dependent on the prejudices and fashions of [your] times,” he wrote in a 1952 journal article [PDF].

“Somebody who reads only newspapers and at best books of contemporary authors looks to me like an extremely near-sighted person who scorns eyeglasses,” he wrote.

2. Don’t jump too quickly from book to book // Seneca

The Print Collector via Getty Images

Seneca the Younger, a first-century Roman Stoic philosopher and trusted advisor of Emperor Nero, believed that reading too wide a variety in too short a time would keep the teachings from leaving a lasting impression on you. “You must linger among a limited number of master thinkers, and digest their works, if you would derive ideas which shall win firm hold in your mind,” he wrote in a letter to Roman writer Lucilius.

If you’re wishing there were a good metaphor to illustrate this concept, take your pick from these gems, courtesy of Seneca himself:

“Food does no good and is not assimilated into the body if it leaves the stomach as soon as it is eaten; nothing hinders a cure so much as frequent change of medicine; no wound will heal when one salve is tried after another; a plant which is often moved can never grow strong. There is nothing so efficacious that it can be helpful while it is being shifted about. And in reading of many books is distraction.”

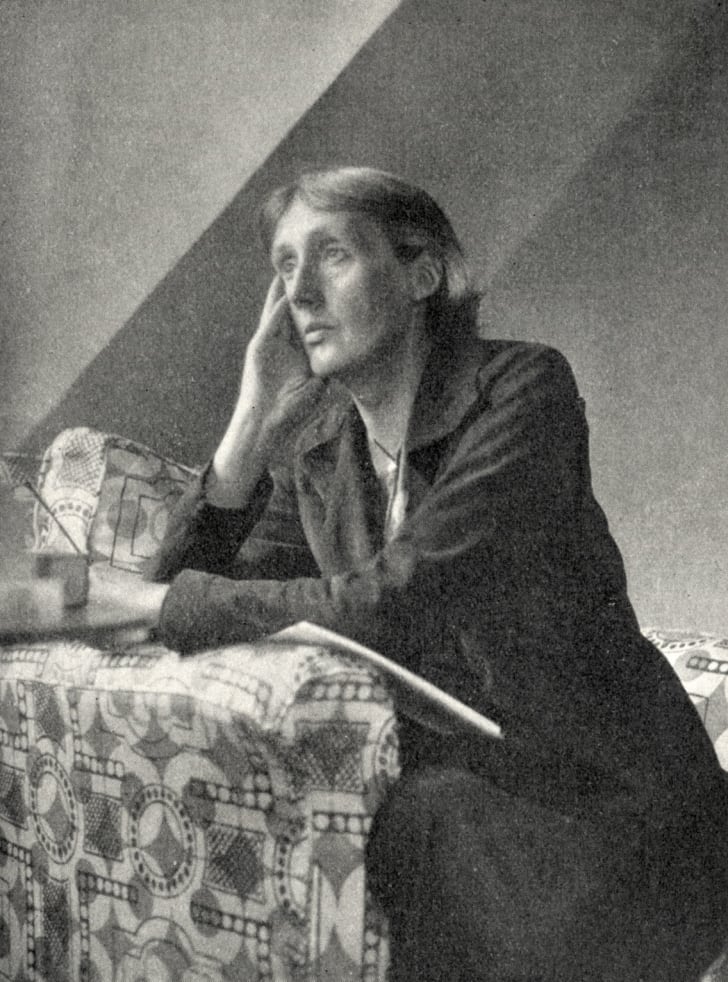

3. Shop at secondhand bookstores // Virginia Woolf

Culture Club/Getty Images

In her essay “Street Haunting,” Virginia Woolf described the merits of shopping in secondhand bookstores, where the works “have come together in vast flocks of variegated feather, and have a charm which the domesticated volumes of the library lack.”

According to Woolf, browsing through used books gives you the chance to stumble upon something that wouldn’t have risen to the attention of librarians and booksellers, who are often much more selective in curating their collections than secondhand bookstore owners. To give us an example, she imagined coming across the shabby, self-published account of “a man who set out on horseback over a hundred years ago to explore the woollen market in the Midlands and Wales; an unknown traveller, who stayed at inns, drank his pint, noted pretty girls and serious customs, wrote it all down stiffly, laboriously for sheer love of it.”

“In this random miscellaneous company,” she wrote, “we may rub against some complete stranger who will, with luck, turn into the best friend we have in the world.”

4. You can skip outdated scientific works, but not old literature // Edward Bulwer-Lytton

The Print Collector/Getty Images

Though his novels were immensely popular during his lifetime, 19th-century British novelist and Parliamentarian Edward Bulwer-Lytton is now mainly known for coining the phrase It was a dark and stormy night, the opening line of his 1830 novel Paul Clifford. It’s a little ironic that Bulwer-Lytton’s books aren’t very widely read today, because he himself was a firm believer in the value of reading old literature.

“In science, read, by preference, the newest works; in literature, the oldest,” he wrote in his 1863 essay collection, Caxtoniana. “The classic literature is always modern. New books revive and redecorate old ideas; old books suggest and invigorate new ideas.”

To Bulwer-Lytton, fiction couldn't ever be obsolete, because it contained timeless themes about human nature and society that came back around in contemporary works; in other words, you can’t disprove fiction. You can, however, disprove scientific theories, so Bulwer-Lytton thought it best to stick to the latest works in that field. (That said, since scientists use previous studies to inform their work, you can still learn a ton about certain schools of thought by delving into debunked ideas—plus, it’s often really entertaining to see what people used to believe.)

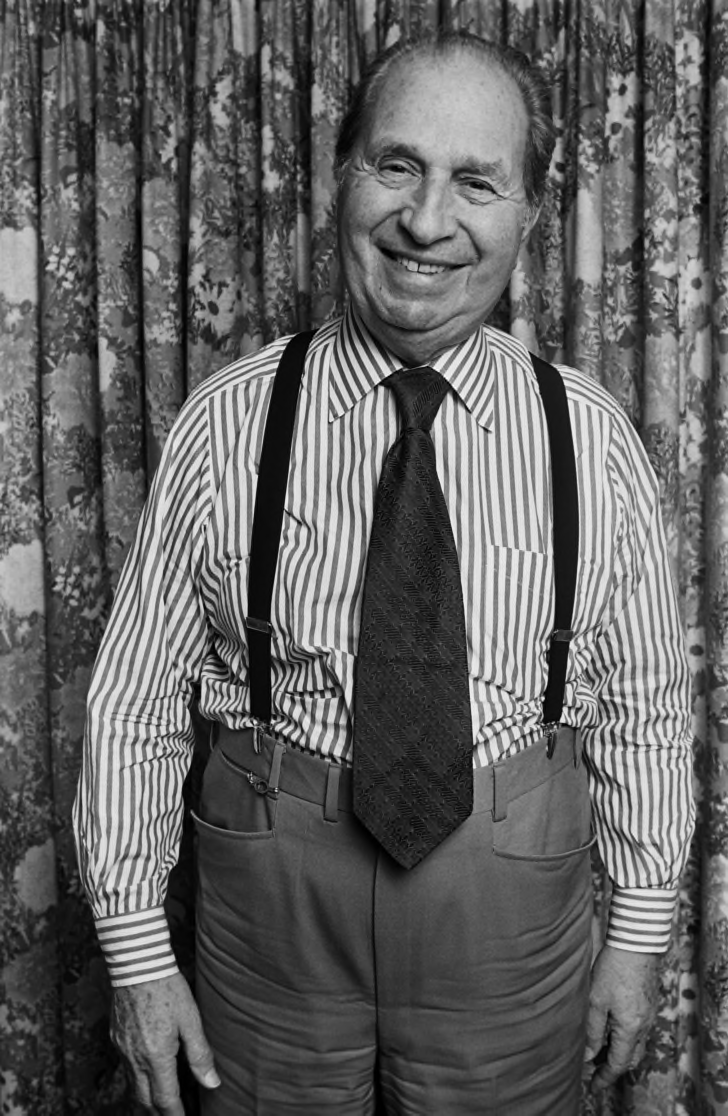

5. Check out authors’ reading lists for book recommendations // Mortimer J. Adler

George Rose/Getty Images

In his 1940 guide How to Read a Book, American philosopher Mortimer J. Adler talked about the importance of choosing books that other authors consider worth reading. “The great authors were great readers,” he explained, “and one way to understand them is to read the books they read.”

Adler went on to clarify that this would probably matter most in the philosophy field, “because philosophers are great readers of each other,” and it’s easier to grasp a concept if you also know what inspired it. While you don’t necessarily have to read everything a novelist has read in order to fully understand their own work, it’s still a good way to get quality book recommendations from a trusted source. If your favorite author mentions a certain novel that really made an impression on them, there’s a pretty good chance you’d enjoy it, too.

6. Reading so-called guilty pleasures is better than reading nothing // Mary Wollstonecraft

Hulton Archive/Getty Images

To the 18th-century writer, philosopher, and early feminist Mary Wollstonecraft, just about all novels fell into the category of “guilty pleasures” (though she didn’t call them that). In A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, she disparaged the “stupid novelists, who, knowing little of human nature, work up stale tales, and describe meretricious scenes, all retailed in a sentimental jargon, which equally tend to corrupt the taste and draw the heart aside from its daily duties.”

If her judgment seems unnecessarily harsh, it’s probably because it’s taken out of its historical context. Wollstonecraft definitely wasn’t the only one who considered novels to be low-quality reading material compared to works of history and philosophy, and she was also indirectly criticizing society for preventing women from seeking more intellectual pursuits. If 21st-century women were confined to watching unrealistic, highly edited dating shows and frowned upon for trying to see 2019’s Parasite or the latest Ken Burns documentary, we might sound a little bitter, too.

Regardless, Wollstonecraft still admitted that even guilty pleasures can help expand your worldview. “Any kind of reading I think better than leaving a blank still a blank, because the mind must receive a degree of enlargement, and obtain a little strength by a slight exertion of its thinking powers,” she wrote. In other words, go forth and enjoy your beach read.

7. You get to make the final decision on how, what, and when to read // Theodore Roosevelt

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division // No Known Restrictions on Publication

Theodore Roosevelt might have lived his own life in an exceptionally regimented fashion, but his outlook on reading was surprisingly free-spirited. Apart from being a staunch proponent of finding at least a few minutes to read every single day—and starting young—he thought that most of the details should be left up to the individual.

“The reader, the booklover, must meet his own needs without paying too much attention to what his neighbors say those needs should be,” he wrote in his autobiography, and rejected the idea that there’s a definitive “best books” list that everyone should abide by. Instead, Roosevelt recommended choosing books on subjects that interest you and letting your mood guide you to your next great read. He also wasn’t one to roll his eyes at a happy ending, explaining that “there are enough horror and grimness and sordid squalor in real life with which an active man has to grapple.”

In short, Roosevelt would probably advise you to see what Seneca, Albert Einstein, Mary Wollstonecraft, and other great minds had to say about reading, and then make your own decisions in the end.