Minimising health risks under Covid – is easing the ban on alcohol the right move?

by Maurice SmithersThe Southern African Alcohol Policy Alliance in South Africa (SAAPA SA) would have preferred to see the ban on both liquor and tobacco continue under Level 3. Second best would have been for the ban on liquor to remain and that on tobacco to be lifted.

The Southern African Alcohol Policy Alliance in South Africa (SAAPA SA) is primarily concerned with public health and human rights. So, while our focus is on liquor-related harm and on influencing liquor policy, we are also mindful of, and concerned about, the challenges of tobacco in relation to public health and human rights.

CLOSE

Nevertheless, SAAPA SA admits to being somewhat baffled by the government’s decision to allow people limited access to liquor under Level 3 of the State of Disaster lockdown regulations, but to continue the ban on tobacco.

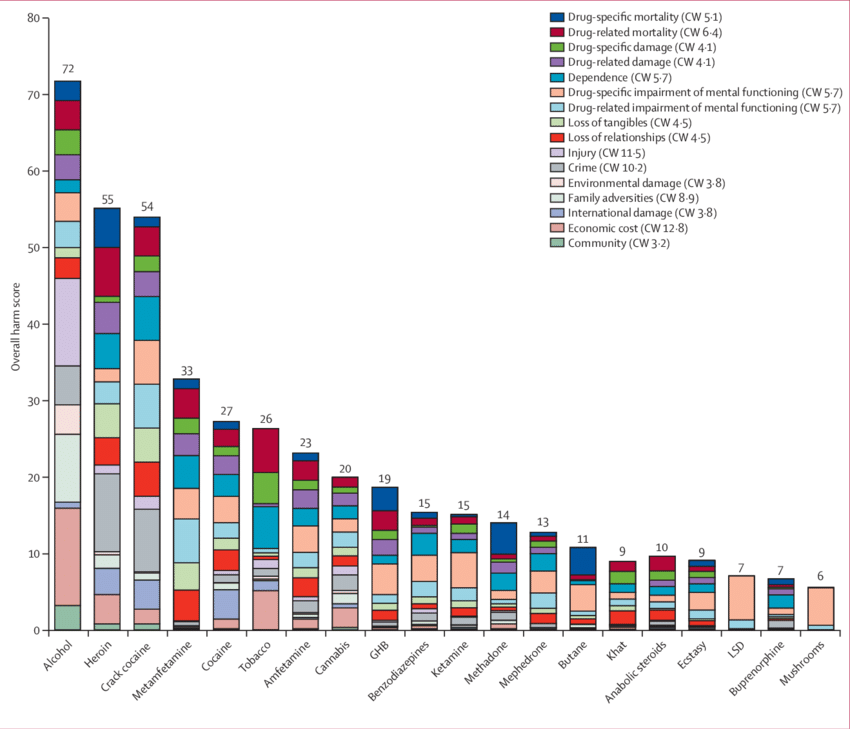

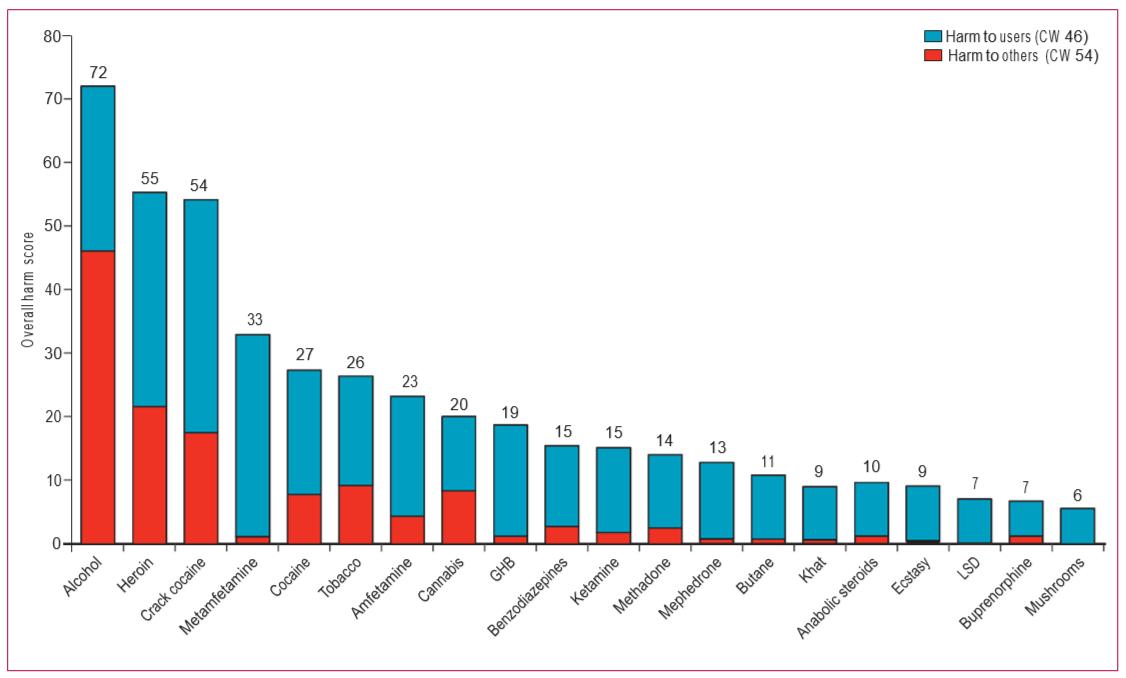

In a 2010 study undertaken by Nutt and others it was found that, out of the 20 most-commonly used recreational drugs in the UK (liquor and tobacco amongst them), liquor caused by far the greatest overall harm to the country and liquor was the only drug among the 20 which caused more harm to the society around drinkers than to drinkers themselves. For the purposes of this article, it is (reasonably) assumed that the results in South Africa would be similar, especially with respect to liquor.

Display Adverts

Tables above: Drug harms in the UK: a multicriteria decision analysis. The Lancet, 376 (9752).

Tough legislation imposed on tobacco in South Africa in 1999 was largely driven by concerns about “secondary smoke”, the idea that smokers pose a comfort and health risk to someone in their vicinity who is not smoking. However, in the Nutt table, tobacco is seen to be the sixth most harmful drug overall in the UK, but clearly more harmful to smokers themselves than to the people around them. And yet liquor, most harmful overall and the only drug more harmful to society as a whole than to individual drinkers, has legislation that is much less onerous.

So why allow access to liquor in preference to tobacco?

After all, no-one has claimed that the ban on tobacco has led to a decrease in crime, interpersonal violence and hospital admissions. However, public health practitioners, researchers and government officials alike have pointed to the likely influence of the ban on liquor transportation and sale on these decreases.

Furthermore, those who drink and smoke will acknowledge that they smoke more when they drink. Research has shown that there are physical and psychological reasons for this (for example, here and here).

There is already a problem of the illicit distribution and sale of tobacco under lockdown. Now that the ban on liquor has been eased, is it not likely that the demand for cigarettes will increase as people start to drink again? This will therefore mean an even greater problem of illicit tobacco trading. But allowing people to buy tobacco products would not have resulted in a sudden upsurge in the demand for illicit liquor. (In saying this, we are not suggesting it has to be either/or; we believe that there are health reasons for maintaining the tobacco ban too).

Display Adverts

Perhaps the key to the government’s decision to allow access to liquor in Level 3, but not to tobacco, is the different ways in which use of these products is currently legislated in South Africa.

The 1999 legislation effectively “denormalised” the use of tobacco which, in previous decades had been ubiquitous in homes, cars and public places, with advertising glamorizing the product on billboards, radio and TV, in newspapers and magazines, and emblazoned on sporting outfits and motor cars. As a result of the legislation, there is much less pressure on people to use tobacco.

Liquor, on the other hand, continues to be promoted as a ‘normal’ and ‘natural’ part of life, and encouraging young people to look forward to turning 18 and being able to imbibe legally (having, in many instances, been partaking illegally for a couple of years already).

Perhaps it is easier to continue to “demonise” a product that has already been “demonised” than one that is aggressively promoted as “part of our culture” and desirable and necessary for “social interaction”.

For the oft-stated public health reasons that led to their imposition in the first place, SAAPA SA would have preferred to see the ban on both liquor and tobacco continue under Level 3 and beyond. Second best would have been for the ban on liquor to remain and that on tobacco to be lifted.

If, however, government’s decision on this is final – and we expect that government will want to avoid a repeat of the public relations disaster that ensued in April when the President said the tobacco ban was to be lifted and the National Coronavirus Command Centre (NCCC) collectively decided otherwise a week later – SAAPA SA proposes the following approach to the easing of the ban on liquor:

- Adoption of a national position – noting that the whole country has moved to Level 3 from 1 June, the same rules must apply in relation to liquor. Different rules in different areas could result in the illegal transportation of liquor from open to closed areas.

- Liquor must not be classified as essential, even if the ban is eased. It remains a product that poses serious public health and safety risks and must be treated as such.

- Limited operating hours – Tuesday to Friday 9am-6pm (not according to current licensing times – some bottle stores are licensed to stay open until 9pm). Mechanisms must be in place to prevent crowds and conflicts and to maintain physical distancing.

- Limits on how much retail customers can buy with each purchase and over a time period, eg weekly – implementation of a register system using identification documents is suggested. SAAPA SA realises that this may be a logistic and technical challenge, but there must be steps in place to limit purchases. The lifting of the liquor ban in Lesotho should be studied, given the rush by consumers there to buy very large quantities, either for stockpiling or for illicit resale. Once again, public health considerations must influence this decision.

- Clear guidelines on how and where outlets who sell to the public acquire their stocks. Introduction of a tracking system for liquor from production to point of sale is an important means of managing liquor and can be introduced now for inclusion in future liquor policy measures. Russia was “the first country to introduce a fully automated system for tracking not only volumes of produced alcohol, but also retail alcohol sales in real time, recognising the status of alcohol as a non-ordinary commodity and responding to the challenges of illegal alcohol markets” – their methodology can be studied in this WHO Report.

- Consider a temporary raising of the age limit from 18 to 21. A permanent change to 21 has already been proposed in the Liquor Amendment Bill of 2017.

- No advertising and no promotional discounts for bulk buying. The liquor industry must be barred from encouraging excessive drinking in any way.

- Equitable approach – the easing of the ban shouldn’t just favour the larger bottle stores and the supermarket bottle stores. In principle, we don’t support allowing on-consumption outlets to sell off-consumption. However, government does need to find a way to ensure the easing of the ban doesn’t favour one section of the community, but whatever mechanism is used must be subject to very clear guidelines and limitations. Meantime, financial support must be offered to liquor traders, as it is to other businesses.

- Keep monitoring the incidence of interpersonal violence, especially male violence against women (gender-based violence) and domestic violence (against women and children). What steps will be taken to mitigate against a possible increase in violence as a result of the availability of liquor?

- Admissions to emergency centres must be monitored to see if easing the ban results in an increase of liquor-related cases and a concomitant reduction in the availability of beds for Covid-19 cases.

- Clear rules about consumption, e.g. availability doesn’t mean people can drink together socially. An intensive and extensive communication campaign should be undertaken, with the primary focus on informing and educating people and only secondarily on law enforcement messaging. People need to understand why to observe Covid-19 regulations, not be terrified into obeying them.

- Maintain phased approach with only clear evidence-based changes beyond level 3, if at all.

- No return to normality – don’t automatically go back to pre-Covid “normality” once the State of Disaster is lifted. Covid-19 is an unexpected and useful opportunity to gather evidence-based data to inform policy going forward. Use the learning from the Covid period, especially the reduction in liquor harm demonstrably linked to the limitations on access, to determine an appropriate new legal framework, based on the Liquor Policy of 2016 and the WHO “best buys” for reducing liquor-related harm.

Finally, it is important to remember that the Road Traffic Amendment Bill of 2015 and the Liquor Amendment Bill of 2017 have already been through a participation process with extensive public support for the measures therein that will help to reduce liquor-related harm. A number of political figures have recently called for better legislation. So now is the time to fast-track these Bills (we note that the Road Traffic Amendment Bill will go to Parliament this year – the Liquor Amendment Bill must also be tabled in 2020). DM/MC

Display Adverts

Maurice Smithers is a long-time social and human rights activist and currently Director of the Southern African Alcohol Policy Alliance of South Africa (SAAPA SA), which aims to give civil society a “loud” voice in the formulation and implementation of public health-oriented liquor policy and to counter the influence of the liquor industry on the framing of liquor legislation

Maurice Smithers

Comments - share your knowledge and experience

Please note you must be a Maverick Insider to comment. Sign up here or sign in if you are already an Insider.