India Is Reviving The Squadron Of Nirmal Jit Singh Sekhon, IAF’s Only Param Vir Chakra Awardee, With LCA Tejas. Here’s His Story

by Kamalpreet Singh GillSnapshot

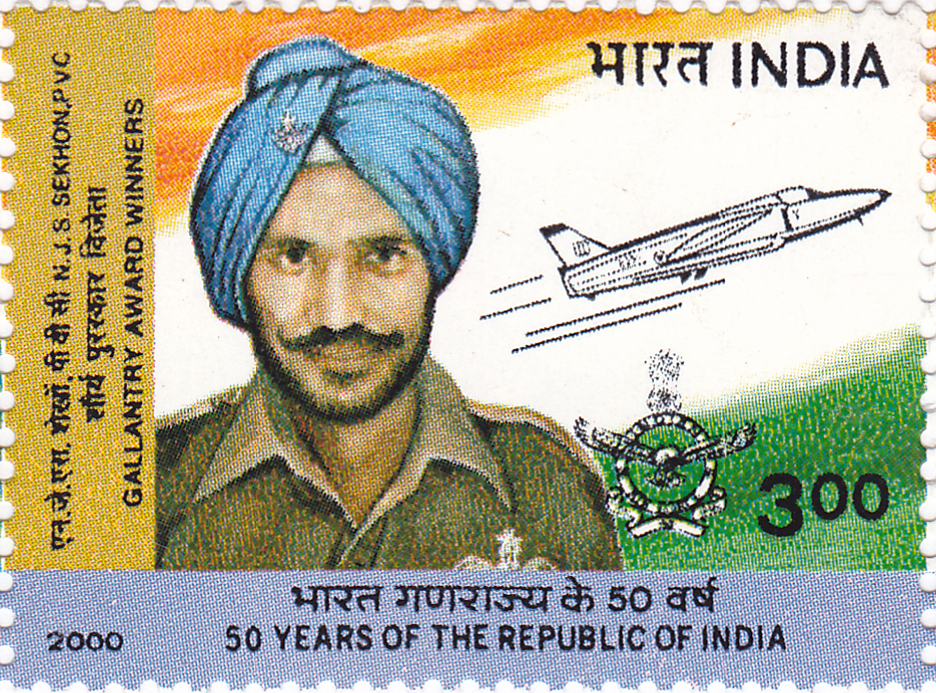

IAF’s 18 Squadron, raised in 1965 and number-plated in 2016, will be made operational at Sulur today (27 May) with the induction of LCA Tejas.

It is known for being the squadron of Flying Officer Nirmal Jit Singh Sekhon, the only IAF officer to be awarded the Param Vir Chakra.

This is his story.

Flying Officer Nirmal Jit Singh Sekhon was only 28 years old when he laid down his life defending the Srinagar airfield on 14 December 1971.

He remains the only Param Vir Chakra awardee from the Indian Air Force (IAF).

Nirmal Jit Singh was born on 17 July 1943 in the village of Issewal Dakha in Ludhiana, Punjab.

Soldiering and farming have been the main occupations of men in this village for generations.

Sepoy Sarup Singh Sekhon (not related to Nirmal Jit Singh) was another soldier from Issewal Dakha who laid down his life during the 1971 war.

Nirmal Jit Singh’s father, Warrant Officer Tarlochan Singh Sekhon, had served the Indian Air Force as well.

As a result, Sekhon was passionate about fighter planes from his childhood.

As a strapping young man of six feet and a good few inches though, he was dismayed to find that he barely managed to fit into the small Gnat fig feet six fighter planes used by the IAF then.

Sekhon had only been married a few months when tensions began to build up on India’s eastern front in March 1971, where the Mukti Bahini was engaged in a bitter struggle with the Pakistani army.

On 3 December 1971, Pakistan launched Operation Chengiz Khan — a series of pre-emptive strikes on India’s western airbases meant to neutralise the Indian Air Force.

The Pakistani offensive, though failed in its objective, marked the beginning of the 1971 India-Pakistan war.

The main thrust of the Indian offensive during the war was on the eastern front, while the western front was meant to contain Pakistan from making any advances.

The Pakistanis, realising their hopeless position in the east, decided to make a fight of it with all their leftover might on the western sector.

In doing so, General Yahya Khan had chosen to rely on the time tested Pakistani strategy — “the defence of East Pakistan lies in the West”.

While the Pakistanis had wanted to make Sri Ganganagar in northern Rajasthan the focal point of their thrust into India, the decisive battles of the war ended up being fought well to the south – Longewala in Jaisalmer, and to the north – Shakargarh in Punjab – of the chosen sector.

While Longewala had been fought and won by 7 December, Indian and Pakistani armies found themselves locked in an eyeball-to-eyeball stalemate in Shakargarh — a bulge of Pakistani territory butting into, and surrounded on three sides by Indian states of Punjab and Jammu and Kashmir.

Attempting to break his way through the stalemate, Gen Yahya Khan decided to use his air force once again to bomb the Indian airfields at Pathankot, Amritsar and Srinagar that were meant to provide support to the Indian offensive in the Shakargarh bulge.

Sandwiched between the Ravi and the Chenab rivers, Shakargarh could be used to launch attacks into the critical Indian cities of Amritsar, Pathankot, Gurdaspur and Jammu, as well as on the Madhopur headworks controlling the waters of the Bari-Doab canal that irrigates much of Indian Punjab.

It was thus critical for Pakistan to keep the Indian Army from taking the Shakargarh bulge, while it prepared its main western offensive a little further to the south near Sri Ganganagar.

Pakistan Air Force’s 26th squadron, stationed at Peshawar, was assigned the task of bombing Indian airfields in Amritsar, Pathankot and Sringar to neutralise the Indian offensive in the Shakargarh bulge.

Flying Officer Sekhon was part of the 18th Squadron of the IAF, which was initially stationed at Ambala.

Under the conditions of the 1948 ceasefire agreement with Pakistan, India was not allowed to station fighter aircraft at Srinagar during peacetime.

Since the war with Pakistan had been declared only on 3 December, Sekhon’s 18th squadron had barely any time to make a rushed move from Ambala and dig in.

Nor were they familiar with the terrain of Srinagar – a circumstance that was to prove critical in the events that were to follow.

Additionally, the Kashmir Valley then did not have any radar coverage.

As a result, the fighters stationed there relied on manual observation by advanced posts using binoculars, a method which was not very helpful given the fog.

The Pakistanis on the other hand were much more familiar with the terrain of Srinagar as it had been their favourite bombing target during previous conflicts.

On the fateful morning of 14 December 1971, Sekhon along with Flight Lieutenant Baldhir Singh Ghumman were on the two-minute stand by — strapped to their seats and ready to take off within two minutes in case of an enemy attack.

The Indian Air Force relied on the British made Gnat aircraft while the Pakistanis used the American made F-86 Sabre.

On the morning of 14 December, six Pakistani F-86 Sabres took off from Peshawar to bomb the Srinagar airfield as they had done many times earlier.

However, this time things were going to be different.

As the Pakistanis dropped their first two bombs, Flight Lieutenant Ghumman, strapped to the seat of his Gnat, and a rush of adrenaline pumping through him, roared off into the air to engage the Sabres.

Sekhon, equally on the edge, took his leader’s take off as clearance to engage and let go off the brakes of his Gnat and charged down the runway.

However, unfamiliarity with the terrain of Kashmir soon caught up with the two IAF pilots as Flight Lieutenant Ghumman, eager to climb higher so as to give himself more height and energy with which to attack the enemy soon lost himself in the haze of the mountains.

Since the IAF had no radar in the Kashmir valley, ground control was unable to help him either.

This left Sekhon alone in his Gnat to tackle the six Pakistani Sabres.

What happened next is best described in the words of the enemy himself.

The following description has been taken from Air Commodore Kaiser Tufail’s book, Great Battles of Pakistan Air Force.

Air Commodore Tufail was one of the pilots in the Pakistani formation that attacked the Srinagar airbase on 14 December 1971.

The other names mentioned in the excerpt are of the other Pakistani pilots of the formation:

Flg Off NirmalJit Singh Sekhon of No 18 Squadron was rolling for take-off as No 2 in a two-Gnat formation, just as the first bombs were falling on the runway. Said to have been delayed due to dust kicked up by the preceding Gnat, Sekhon lost no time in singling out the first Sabre pair, which was re-forming after the bombing run. Changazi was, however, quick to detect the attacker behind his wingman. Gnat behind, all punch tanks,” yelled Changazi. No 3 (Andrabi), who was just pulling out of the attack, was horrified to see the Gnat no more than 1,000 ft and firing at Dotani. “Break left,” called Andrabi, as he himself maneuvered to get behind the Gnat. Dotani, who had been turning frantically, found his low-powered Sabre tottering at the verge of stall. Unable to hang around any longer with such a precarious energy state, he decided to make a getaway.

As Sekhon, the lone warrior charged down on the six Pakistani fighters with his guns blazing, two of them panicked and headed back home to Peshawar, damaged from the fire from Sekhon’s Gnat.

This left four Sabres and Sekhon’s Gnat. Still determined to give them a tough fight, Sekhon continued to circle the enemy aggressively.

Pretty soon, the Pakistani Sabre firing incessantly on Sekhon had emptied its entire stock of 1,800 bullets on Sekhon’s Gnat without bringing him down.

With no ammunition left, the third Pakistani Sabre too was now effectively out of action.

This left Sekhon and three Pakistani Sabres in the field.

Seconds later though, the ground staff noticed thick black smoke bellowing from the Gnat.

Sekhon had been hit and was going down fast. Unfortunately, Sekhon did not have time to evacuate.

The dogfight had happened at very low altitude and the Gnats were notorious for having issues with their elevator trims that help to stabilise the aircraft.

The Air Traffic Controller on the ground picked up Sekhon’s last words – “I think I’ve been hit Ghumman, come and get them”.

Flight Lieutenant Ghumman though remained hampered by the haze, was unable to spot Sekhon or the attackers.

Much later, a search party found the wreckage of Sekhon’s Gnat a few miles from the airfield.

No less than 37 bullet marks were counted on the recovered part of the wreckage.

Incidentally, this also happened to be the spot where India’s first ever Param Vir Chakra recipient, Major Somnath Sharma, had fallen while evicting Pakistani infiltrators from the Srinagar airfield in November 1947.

Sekhon’s sacrifice did not go in vain.

PAF’s strategy of bombing the northern airfields was based on the low strength of the IAF in the sector as well as on exploiting the ceasefire agreements that had prevented India from stationing any aircraft in Srinagar during peacetime.

Stung by the valiant fight from the heavily outnumbered IAF and afraid to lose any more of its precious Sabres, the PAF did not risk any further major operations in the northern sector.

The Indian Army was able to successfully launch its offensive into the Shakargarh bulge, culminating in the famous Battle of Basantar in which Second Lieutenant Arun Khetarpal and Colonel Hoshiar Singh won the Param Vir Chakra for showing exemplary courage and bravery.

Nirmal Jit Singh Sekhon’s father, Warrant Officer Tarlochan Singh Sekhon, collected the Param Vir Chakra awarded to his son on 26 January 1972.

Later in life, Warrant Officer Sekhon suffered a paralytic stroke that affected his sight and hearing, but IAF officials from the nearby Halwara airbase extended all possible help to the father of their most decorated hero, caring for him as a venerated member of the family.

Today, a statue of Flying Officer Sekhon along with his beloved Gnat fighter plane adorns the district court complex of Ludhiana, a gentle reminder of the sacrifices our heroes and their families make for our freedom.

(This piece was originally published here in December 2017.)