Are the Coronavirus Bailouts Working? What We Know So Far

If the crisis persists, Congress, the Treasury Department and the Federal Reserve may have to rewrite their playbooks.

by Timothy L. O'Brien, Nir KaissarThis is the first of two columns.

Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell and Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin are presiding over the most massive economic bailout in U.S. history, a Herculean effort to blunt the impact of the coronavirus by buttressing workers and families, businesses and credit markets, the health care and education systems, and state and local governments with at least $5.7 trillion in public funds and guarantees.

House Speaker Nancy Pelosi recently upped the ante, proposing another $3 trillion in federal spending, but her House bill has received a chilly reception from Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell. Among other things, Pelosi’s plan would double down on aid to workers and beef up support for local governments while signaling Democrats’ broader priorities.

The House bill also addresses shortcomings in the previous round of funding and, by promising to commit more taxpayer dollars, highlights questions central to the rescue: Will it work? Is the money getting into the right hands? And how much needs to be spent?

Covid-19 remains the wild card in all this. If the coronavirus stops savaging lives and the economy soon, then the bailout’s scope and duration will come into focus. If the virus remains deadly — particularly if a second surge appears later in the year — then government lifelines will need to lengthen and the bailout’s playbook may need to be rewritten.

In testimony before the Senate Banking Committee last week, the first in a series of quarterly updates on the bailout, Powell noted that 20 million Americans have lost their jobs and a “precipitous drop in economic activity has caused a level of pain that is hard to capture in words.” He said the Fed is “committed to using our full range of tools to support the economy in this challenging time even as we recognize that these actions are only a part of a broader public-sector response.”

Mnuchin, at the same hearing, said coronavirus lockdowns were easing and he expected the economy to begin rebounding by late summer. “I am proud to have worked with all of you, on a bipartisan basis, to get relief into the hands of hardworking Americans and businesses as quickly as possible,” he said. “While these are unprecedented and difficult times, these programs are making a positive impact on people.”

The actions of both the Fed and Treasury should be measured by their speed and impact, as Mnuchin noted. While the pace of their actions has been relatively easy to track, their impact has been more difficult to gauge, in part because it’s still early but also because so much of the response remains murky. Powell and Mnuchin have offered only broad outlines of the bailout so far. Powell promised the Senate he will provide greater detail about the Fed’s actions later on. Mnuchin told senators that the Treasury Department also takes pride in being transparent, drawing some skepticism from Senator Jon Tester, a Democrat, who complained about a lack of disclosure from the agency. Mnuchin insisted that details could be found online, but Treasury’s own website only offers general information about the bailout and doesn’t disclose who or what is getting funding.

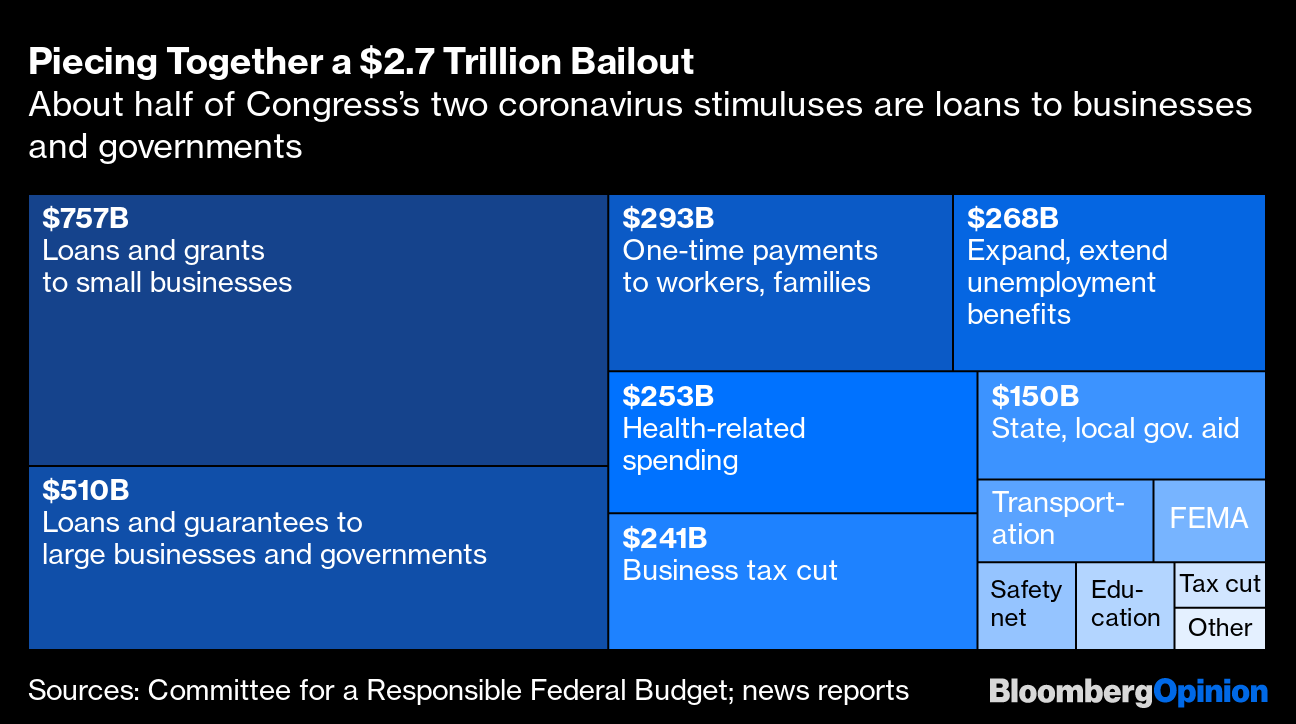

The following chart outlines how $2.3 trillion in federal spending and other support mandated under the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act is being allocated. It also includes an additional $380 billion that Congress was forced to provide to small businesses after a first round of funding missed its mark:

The government was quick to get one-time payments to average Americans after the CARES Act became law on March 27. Mnuchin testified that $240 billion of the $293 billion allocated has gone out. But if the pandemic drags on and people remain out of work, those checks, pegged at $1,200 for adults and $500 per child for each worker who makes $75,000 or less annually, won’t provide nearly enough relief. (Mnuchin said a typical four-person family received $3,400.)

Laid-off workers are also eligible to receive an extra $600 a week in unemployment insurance, which has provided meaningful support and sparked a shortsighted debate about incentives. States generally offer 26 weeks of unemployment; the CARES Act extends that by 13 weeks.

More than half of CARES Act funding, about $1.57 trillion of $2.7 trillion, has been pledged to small and large businesses. Corporate tax cuts worth $241 billion took effect immediately. Another $510 billion earmarked for aid to big businesses, local governments and the U.S. Postal Service has been more of a mystery. The Postal Service is supposed to get $10 billion, but the White House has withheld the money in a political tug of war. The other $500 billion hasn’t been disbursed. Mnuchin has direct control of $46 billion; the remaining $454 billion is under Powell’s control and is intended to prop up a designated set of Fed lending programs.

In his testimony, Powell said that one of those programs, aimed at mid-size businesses, should be running by June. Senators pushed Powell and Mnuchin to answer whether they’d ultimately be willing to absorb a loss on the entire $454 billion. “There are scenarios,” Mnuchin said, “where we could lose all of our capital, and we’re prepared to do that.” (A reminder: When Mnuchin refers to “our capital,” he’s talking about taxpayers’ money.)

Most of the $46 billion in corporate aid that Mnuchin controls is meant for airlines. Treasury hasn’t fully disclosed the terms of that aid, though several major airlines that have applied for support have said the loans carry provisions that could grant the government equity stakes in their operations. This aid is to be a combination of low-interest loans and $25 billion in payroll support for furloughed workers. Although none of the loans have been disbursed, at least $19.2 billion for airline workers has. In the Senate hearing, Senator Elizabeth Warren pressed Mnuchin on how he would ensure that airlines spend the money on workers. Mnuchin replied that companies would have to make “their best efforts” but didn’t say how he would go about making sure they did.

Ignoring such details, intentionally or not, has scarred the other big bailout push: support for small businesses. Since March, $729 billion has been earmarked for entrepreneurs. But the Treasury Department and the Small Business Administration fumbled the rollout of the first $349 billion of that pile, leaving most small businesses in the lurch and channeling a significant share of the money into the coffers of relatively large and well-heeled companies. The second round of funding appears to have reached more authentically small businesses in a more diverse range of states and communities. But Mnuchin has provided no details on exactly which companies have received money, so the program remains hard to assess.

Mnuchin told the Senate that $530 billion in so-called Paycheck Protection Program funds has been granted to entrepreneurs. That funding, which comes from the $729 billion pool, is meant to allow small businesses to keep workers on the payroll. But here again, Mnuchin and the Treasury Department haven’t disclosed how they will make sure the money is used that way.

Mnuchin also said Treasury has sent about $150 billion to state, local and tribal governments. That’s a reasonable start, but it won’t be enough to backstop local budgets devastated by the coronavirus. Pelosi estimates that local governments may need as much as $1 trillion to navigate the crisis — a figure several Democratic governors have also said they’ll need to avoid mass layoffs of public workers and cutbacks in essential services. Some congressional Republicans and the White House have looked askance at those numbers. McConnell has said it may be best to let state and local governments go bankrupt — a risky and ill-informed approach he somehow failed to mention when he approved sending hundreds of billions toward the business community.

On the monetary side, Powell has been quick and bold. He’s had little choice. Coronavirus lockdowns crushed demand for nonessential goods and services, causing massive layoffs and threatening to undermine huge swaths of the economy. Two months ago, parts of the financial system were also on the brink of collapse. Many Wall Street veterans who experienced the grueling 1987 and 2008 market breakdowns say the upheaval in mid-March was worse. The primary culprit was an old-fashioned run on the credit system: Investors scrambled to raise cash by unloading bonds, but they found few buyers. The mismatch caused markets to seize, making it difficult for investors to transact and for companies and municipalities to fund payrolls, pay vendors and maintain services. Credit spreads, or the difference in yield between Treasuries and bonds of less reputable borrowers, widened at the fastest pace on record.

Powell wasted no time revisiting and even expanding some of the emergency measures the Fed deployed in 2008. He dropped short-term interest rates close to zero and signaled he’d keep them low until the economy got back on track. To keep bond markets liquid and functioning, he scooped up Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities, loaned money to primary dealers in credit markets, and offered unlimited support to money markets. It was a muscular show of strength — and faith in the long-term viability of U.S. markets. Bond markets rebounded almost immediately.

Of course, this crisis isn’t just a financial one. Powell knows that the fortifications he’s built will crumble if the business community and state and local governments continue shedding millions of workers because they can’t make or raise money. So he’s taken the Fed into new territory by positioning it to lend directly to companies and municipal governments. Based on Powell’s testimony and available data, it appears he has done little with this power so far. The Fed is a financial behemoth, and a display of good faith — absent an actual show of force — is sometimes enough to steady markets even in chaotic times. Powell may be wagering that gestures are enough for now. But the coronavirus crisis is a seismic event, and it may well test the Fed’s ability to not only aid markets but also rescue corporations and municipalities.

In these early stages, Powell has enjoyed some advantages that Mnuchin hasn’t had. The digital and financial levers he pulls to steady markets — such as adjusting interest rates and buying debt — are more direct and speedy than the loans, guarantees and other tools Mnuchin has at his disposal. Powell is also able to act with more autonomy and has committed to spending as much as it will take to right the economy. Mnuchin, the White House and Congress have often been caught up in disagreements — some that need to be hashed out, some that don’t — about the scope of the stimulus.

Nevertheless, Powell’s promises may not be easy to keep if the virus menaces communities and the economy longer than policy makers expect. If things get melty again, the scale of the stimulus required to keep the economy on life support will probably be much larger than the Fed’s current commitments. In theory, Powell can keep printing money. But the Fed’s balance sheet has already grown to roughly $7 trillion, from $4 trillion at the beginning of the year, an unprecedented swelling. (Before 2008, the Fed’s liabilities had never risen above $1 trillion.) We arrived at our estimate that the bailout thus far represents a $5.7 trillion commitment by combining the growth in the Fed’s balance sheet ($3 trillion) with the amount committed under the CARES Act and associated programs ($2.7 trillion).

Widespread concerns that more federal spending will spark inflation are understandable but overstated. As long as consumers are hiding at home, watching their budgets or even enduring layoffs, they’re likely to spend less — and consequently prices are more likely to fall than rise. But that won’t stop business and political leaders from resisting further monetary and fiscal firepower to combat the crisis. The pushback that greeted Pelosi’s spending bill shows how heated the disagreements might become.

There are other difficulties, too. If Powell has to engage in direct lending, he will discover how difficult it is to effectively oversee a loan program involving countless companies and municipalities. Such an effort can easily unwind if not managed with foresight and attention, as Mnuchin has discovered. And should the economy weaken further, it’s not clear how the Fed would handle what might become a wave of defaults.

Getting into the lending business will plunge Powell into a morass that his predecessors were eager to avoid. He or his lieutenants will inevitably have to choose who receives a bailout and who doesn’t, a process of picking winners and losers that was wildly unpopular during the 2008 bailouts. Also, some of the money for Powell’s credit facilities is appropriated by Congress through the CARES Act, and that blurs the line between the passions of partisan politics and the cold calculation of monetary policy that the Fed has always tried to embrace.

The federal government has undoubtedly moved speedily to confront the coronavirus crisis, and for that everyone involved should take a bow. When Mnuchin and Powell say they needed to act quickly, they should be taken at their word. It was essential to have the extra payments and enhanced unemployment benefits Mnuchin channeled to workers, as well as the backstops Powell engineered for financial markets.

On the other hand, federal policy makers have been dangerously slow to support public health care and state and local governments, and this dithering could come back to haunt them. What’s more, given the lack of oversight, it’s impossible to know whether Congress’s massive experiment in corporate and small business lending might have been — and still might become — more efficient and effective if handled differently.

If the crisis settles down, some of this may not matter. But if it persists or accelerates, the federal government will need to answer a list of knotty questions: What is the best way to support millions of laid-off and furloughed workers when their unemployment insurance expires? Should big corporations be rescued, and if so, which ones? What about small businesses? How can the government ensure the continued viability of essential services such as education, transportation and health care amid a chaotic pandemic?

We’ll try to answer those questions in a second column on Thursday.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

To contact the authors of this story:

Timothy L. O'Brien at tobrien46@bloomberg.net

Nir Kaissar at nkaissar1@bloomberg.net

To contact the editor responsible for this story:

Mary Duenwald at mduenwald@bloomberg.net