John Robertson: Nottingham Forest legend and an overlooked genius

On the eve of the 40th anniversary of Nottingham Forest's European Cup victory over Hamburg, Adam Bate reflects on the genius of John Robertson with the help of the winger's fellow team-mates that day, Garry Birtles and Martin O'Neill…

by Adam Bate

Time can distort the legacy of a player and there are occasions when a bit of scepticism could be forgiven, such is the tendency for rose-tinted memories. Strikers who have never missed a chance since retiring. Midfielders who never misplace a pass from the studio.

But there are other players who seem to drift so far from the conversation when the greats of the game are being discussed that it is hard to pinpoint exactly why.

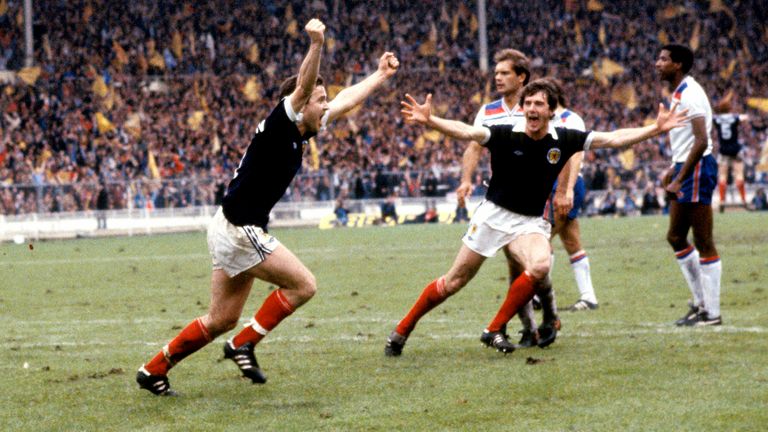

This week marks 40 years since John Robertson's goal secured back-to-back European Cup wins for Nottingham Forest in the Bernabeu. Having also produced the dribble and cross for the only goal of the previous year's final, he was arguably the decisive figure in both games.

No British club has retained the European Cup since.

Brian Clough called him the Picasso of football, a genius with the ball at his feet. Bill Shankly said he could pass with the smoothness of a snooker player striking the cue ball.

But how many are aware of Robertson's greatness?

It is not that his achievements have been erased. A while back, a national newspaper still ranked Robertson among the greatest half a dozen wingers in the history of English football.

But even then, there are those who would consider sixth a little low.

The knights of the game, Sir Stanley Matthews and Sir Tom Finney did not have "that extra on top" that Robertson had, according to Nottingham Forest coach Jimmy Gordon.

Meanwhile, John McGovern, the team's captain for those triumphant nights in Munich and Madrid has pointed out that Ryan Giggs had only one good foot while Robertson had two.

As for George Best, to paraphrase Clough's old line about Sir Alex Ferguson prior to his 2008 triumph in the competition, he might be good but he doesn't have two European Cups.

That only leaves Cristiano Ronaldo, which might give you a clue as to how highly Robertson is regarded by those who saw him up close. Twice since the turn of the century they have voted for the greatest ever Forest player and twice the poll has turned up the same name.

But beyond Nottingham, does the name resonate as it really should?

Maybe the fact that Robertson is Scottish is a factor, although that has not stopped Sir Kenny Dalglish being revered. Maybe not playing for a Liverpool or a Manchester United means that the tales of wonder do not continue to reverberate in quite the same way.

Maybe it is something as silly as the name itself. After all, he is not even the last Scotsman called Robertson to lift the European Cup let alone the last man by the name of John.

Craig Bellamy tells a tale of being so bemused by the notion that this portly figure seen shuffling around as assistant to Martin O'Neill during his days at Celtic was once one of the game's great players that he refused to believe it even when he knew it to be true.

So when praise is heaped upon Robertson, there is always that sense of a wrong that needs to be righted. That, if not quite forgotten, his genius remains somehow overlooked.

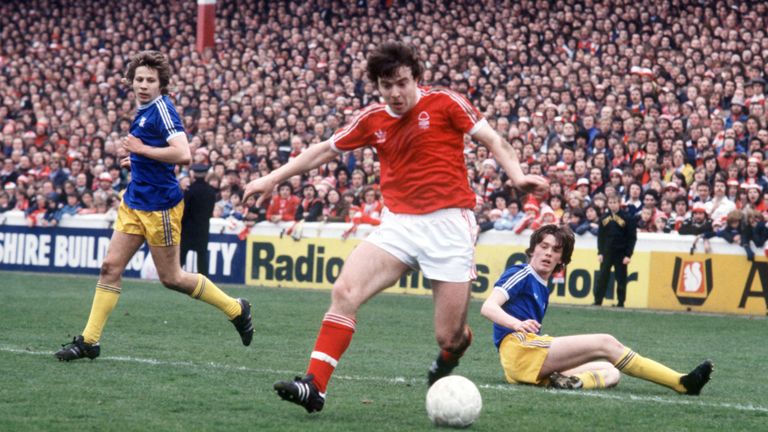

Speak to Garry Birtles about his old team-mate and he feels few deserve to be mentioned in the same breath with the man he rates as a better crosser than Beckham - with either foot.

"Watch our games," he tells Sky Sports. "Watch what John Robertson could do. Bloody hell. On those horrible pitches. In the semi-final against Cologne in 1979, he was just staggering."

His contemporaries knew it, of course. He was the man to stop. The player through whom Forest's attacks were constructed despite his outpost on the left touchline. Robertson was the only Forest outfield player in the PFA team of the year in their title-winning season.

But while the accomplishments of, say, an Eric Cantona or a Steven Gerrard, appear to grow in the telling, it has become all too easy to park Robertson's achievements in the past.

That is a pity because his is a tale worthy of a movie script. A smoker and drinker, with a paunch and a penchant for fried food, his prospects at Forest did not appear particularly good when Clough's predecessor Allan Brown greeted him as Jimmy not John.

But the arrival of Peter Taylor in the summer of 1976 prompted a memorable meeting in which the incoming assistant berated his professionalism and threatened to throw him out.

He did not do so for only one reason - the boy could play. It was all that Robertson needed to hear. With coaches who believed in his talent, he carried Forest along on a journey that few could have imagined happening and none could have imagined happening without him.

It is a reminder that even greatness can be a fragile thing.

That is something worth remembering because it has made for a curious juxtaposition in recent days to see Mental Health Awareness Week coincide with the praise for The Last Dance, the show celebrating Michael Jordan's basketball success with the Chicago Bulls.

On the one hand, we are left in no doubt as to the importance of a compassionate and open environment to allow people to thrive. On the other hand, Jordan speaks of making life hell for his team-mates, they talk of fearing him, and that is seen as the template for success.

The message is clear - winners do not tolerate weakness.

Robertson was a winner, that much is self-evident. He was a leader in his own way too, taking responsibility on the pitch by making the difference in the very biggest of games.

But his lack of self-belief could be crippling. He has spoken since of how he would drive O'Neill to distraction because of his need for constant reassurance after games - a state of affairs that is confirmed in confirmation with his old team-mate.

"That was John," O'Neill tells Sky Sports. "That was his character."

It is why Robertson bristles at the suggestion that Clough ruled by fear. He could be withering in his criticism - as O'Neill could attest - but aside from a jibe or five about Robertson's weight, he rarely directed his barbs at those who could not take it.

"All people need a bit of a confidence boost at different stages," says O'Neill.

"When John was playing, when he was on the field, the manager was always right behind him. The manager gave him that great confidence to play and John repaid that confidence that the manager gave him by being absolutely terrific for the team. Absolutely terrific."

Trust in talent. Clough did that, even though Robertson insists that the urban legend about him being allowed to have a cigarette during the half-time team-talk happened only once.

Clearly, this was a player from a different era. But perhaps it is Clough's own verdict delivered 40 years ago - May 27 1980 - on the eve of that second final that sums it up best.

Asked how Forest would cope against Manny Kaltz - "considered to be the best right-back in the world at that time," according to O'Neill - Clough could not contain his smile.

"We have got a little fat guy who will turn him inside out," he replied.

Robertson proceeded to do just that. "European Cup glory was for the likes of Puskas and Di Stefano," the man himself would later recall, "not for a tubby little lad from Uddingston."

But he was wrong about that. And that should never be forgotten.