11 vaccine giants: How they're fighting COVID-19

Is it desperation, profit motive or good science that's pushing vaccine out?

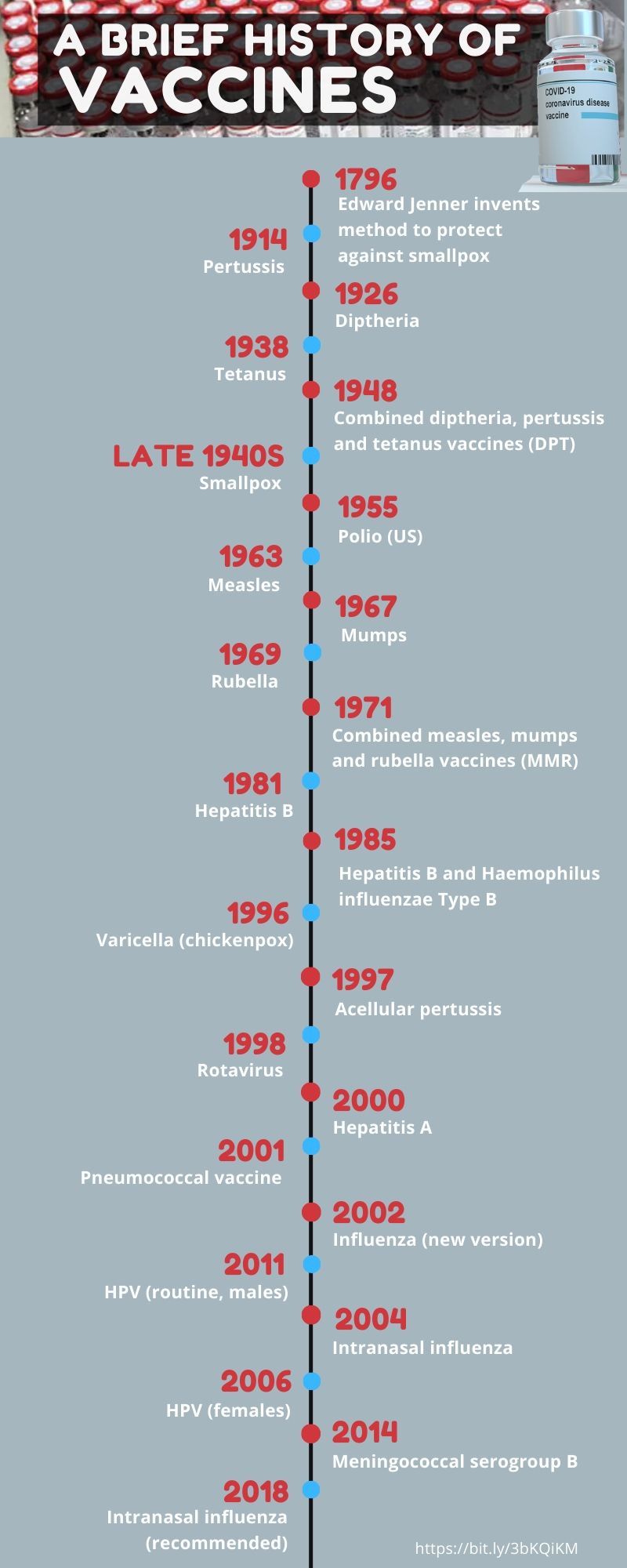

by Jay Hilotin, Assistant EditorDubai: Since the time of Edward Jenner, a British doctor who developed the smallpox vaccine in 1796, vaccines have become one of man's most effective disease-fighting tools.

But the story of vaccines is spotty, with breakthroughs relatively few and far-between.

In 1916, a polio outbreak (two years before the onset of the deadly "Spanish Flu") killed 22,000 patients, infected 500,000 and left thousands paralysed, including US President Franklin D Roosevelt (who served from 1933-1945).

The culprit — the poliomyelitis virus — was already identified by then. But it took another 39 years or so to develop a polio vaccine (in 1955).

How much time would it take to develop a COVID-19? Given its deadly run, it is pushing today's science to the edge of what's possible. The pandemic has locked us all down, crushed the global economy, infected 5.6 million people and killed over 350,000 people so far.

While the SARS-CoV-2 infection rages on, moving from one epicentre to another, there's a heightened effort among pharmaceutical companies big and small, with a keener sense of mission to speed up the fight and beat this virus.

Accelerated vaccine development

It’s not just a global health crisis. The loss of lives and jobs makes a vaccine all the more urgent.

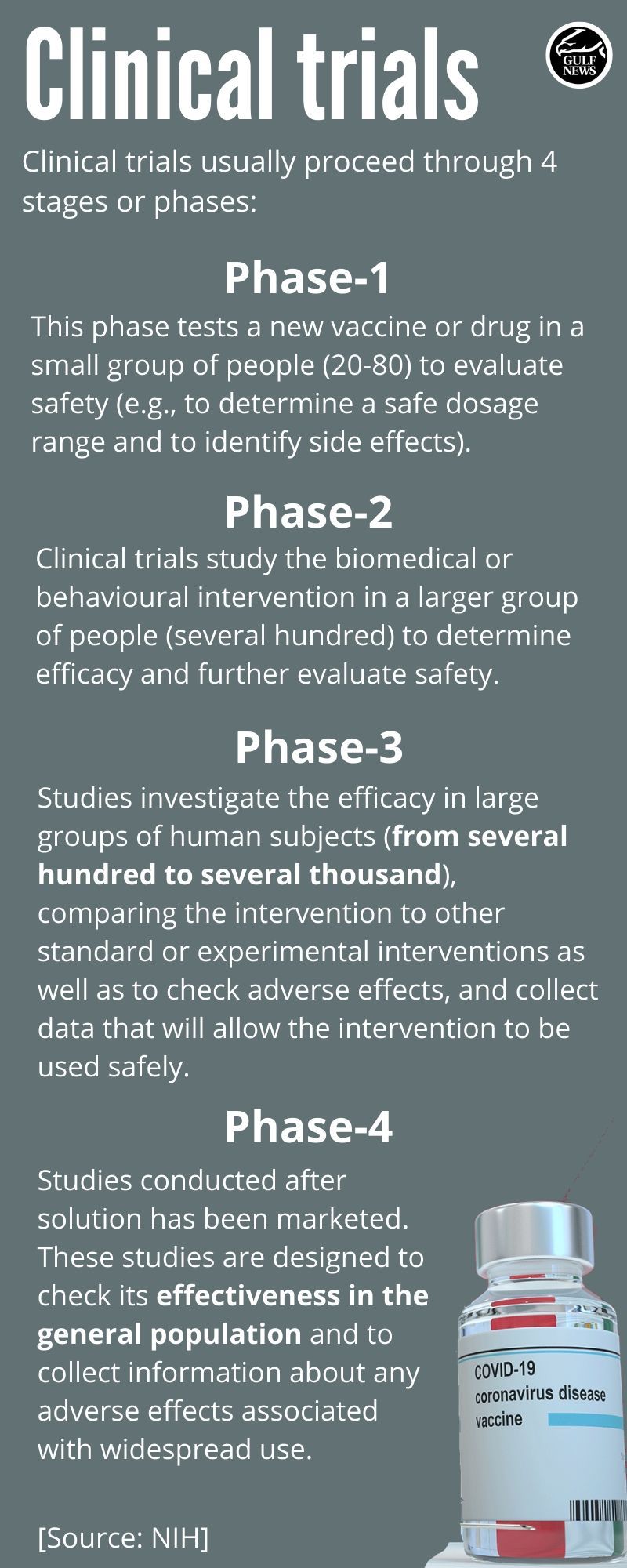

Now, there are dozens of clinical trials underway, though up to 60 per cent are still in the pre-clinical, patient-recruiting stage. But there are some signs of progress.

As of Wednesday, May 27, 2020, at least two candidate vaccines are already on Phase 2/3 of human trials, according to the RAPS tracker.

HOW DO VACCINES WORK?

In a nutshell, they enhance the body’s natural ability to fight pathogens, or agents that cause diseases.

Vaccines work by training the body to recognise and respond to the proteins produced by disease-causing organisms, such as a virus or bacteria.

So, in a way, they enable and boost your body’s immunity, by building antibodies that naturally fight against serious infections and illnesses.

Vaccines “train” and strengthen the body’s immune system to develop resistance against anti-bodies and illnesses by imitating an infection, using a “killed” (harmless, or attenuated) version of the virus that causes that infection, to create a natural immune response.

After they have completed the process of creating a stronger immune system, most of the active types of vaccines remain in your system as anti-bodies.

Vaccine development, however, is expensive, laborious and time-consuming: It takes 16 years, on average, to develop a vaccine via the traditional, four-phase route.

The unusual, disruptive result of the current pandemic, however, has pushed biopharma majors as well as new players to pool resources. Several countries have poured billions of dollars into the effort.

VACCINE: 4 TYPES

Vaccines are generally classified into four types, that may be administered to both infants and adults.

• Live-attenuated vaccines (reducing the virulence of a pathogen, but still keeping it viable (or "live")

• Inactivated vaccines (aka "killed" vaccine, consisting of virus particles, bacteria, or other pathogens that have been grown in culture and then lose disease producing capacity.)

• Subunit, recombinant, polysaccharide, and conjugate vaccines

• Toxoid vaccines (A vaccine made from a toxin (poison) that has been made harmless but that elicits an immune response against the toxin)

The result: Dozens of experimental vaccines are now going at “warp-speed”. This cadence is enabled in part by key advances in genetic engineering, alongside novel vaccine “platforms” developed only recently.

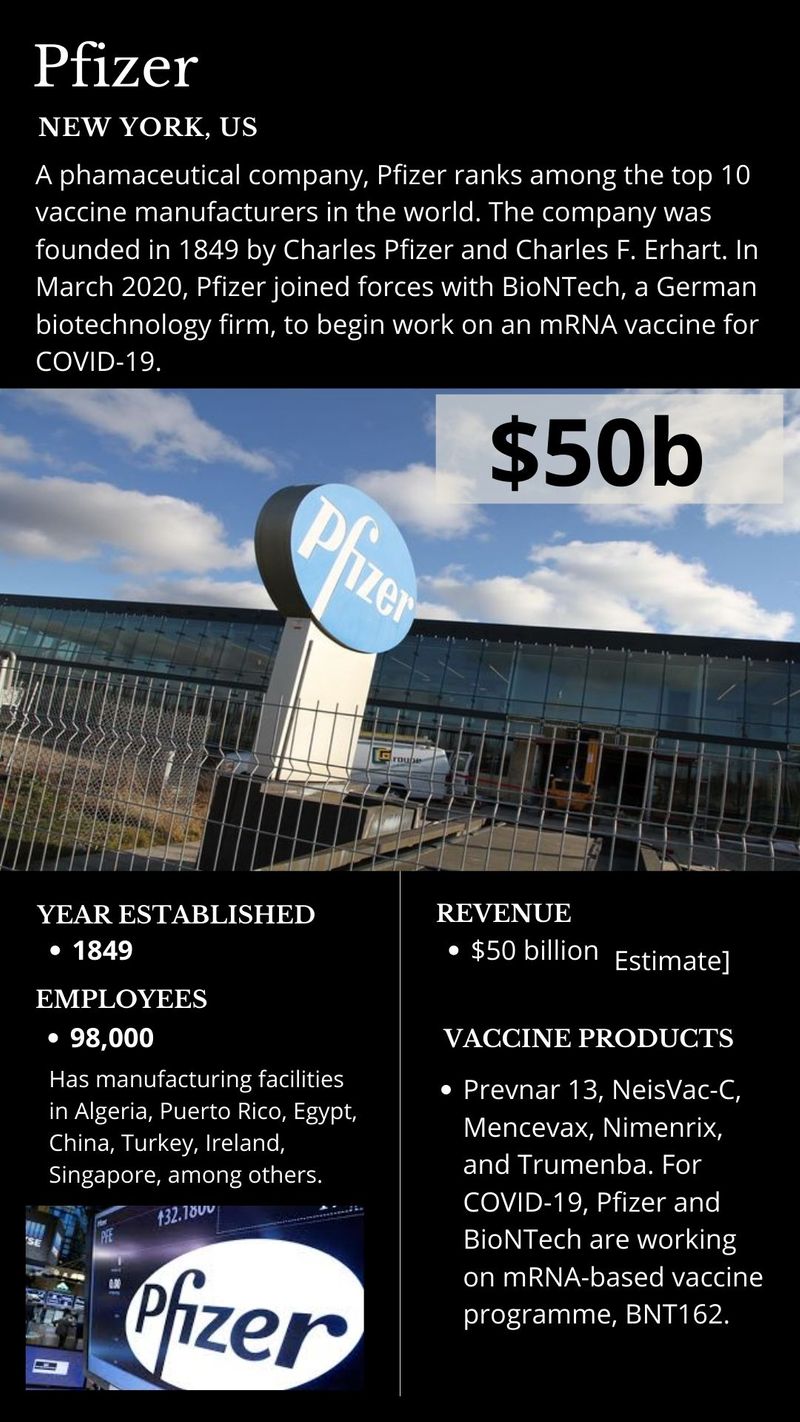

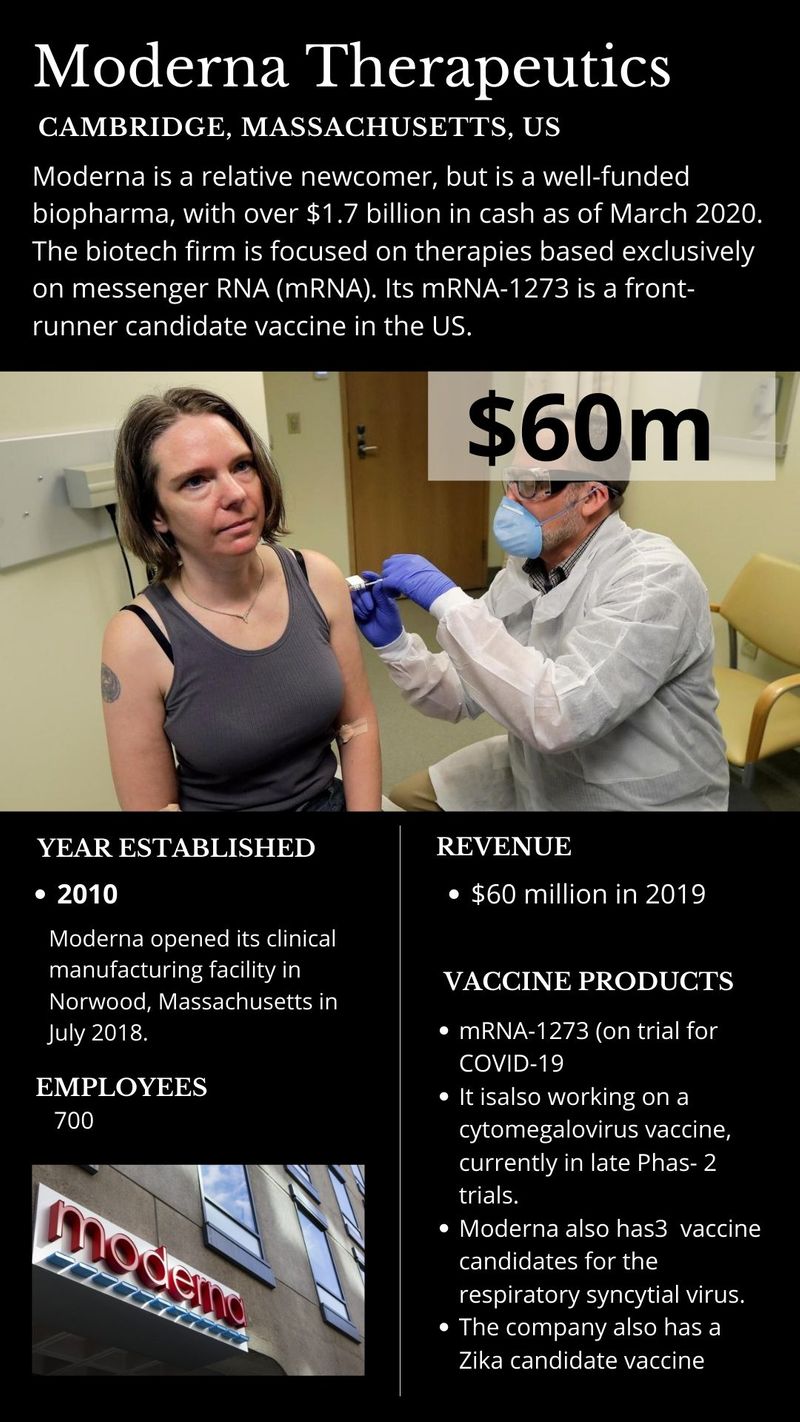

For one, the use of messenger RNA, a relatively new way of vaccine development, offers advantages in speed and scalability. So far, no such vaccine has been licensed for infectious diseases. If trials prove successful, it would be a breakthrough, and may accelerate vaccine development for other infectious diseases. But till the trials are done and dusted, it's all touch-and-go with the mRNA route.

In this global race, there’s bound to be a winner — or winners. That, at least, is the hope of everyone. It's quite possible a winning vaccine may come out as early as late 2020, or early 2021, say experts.

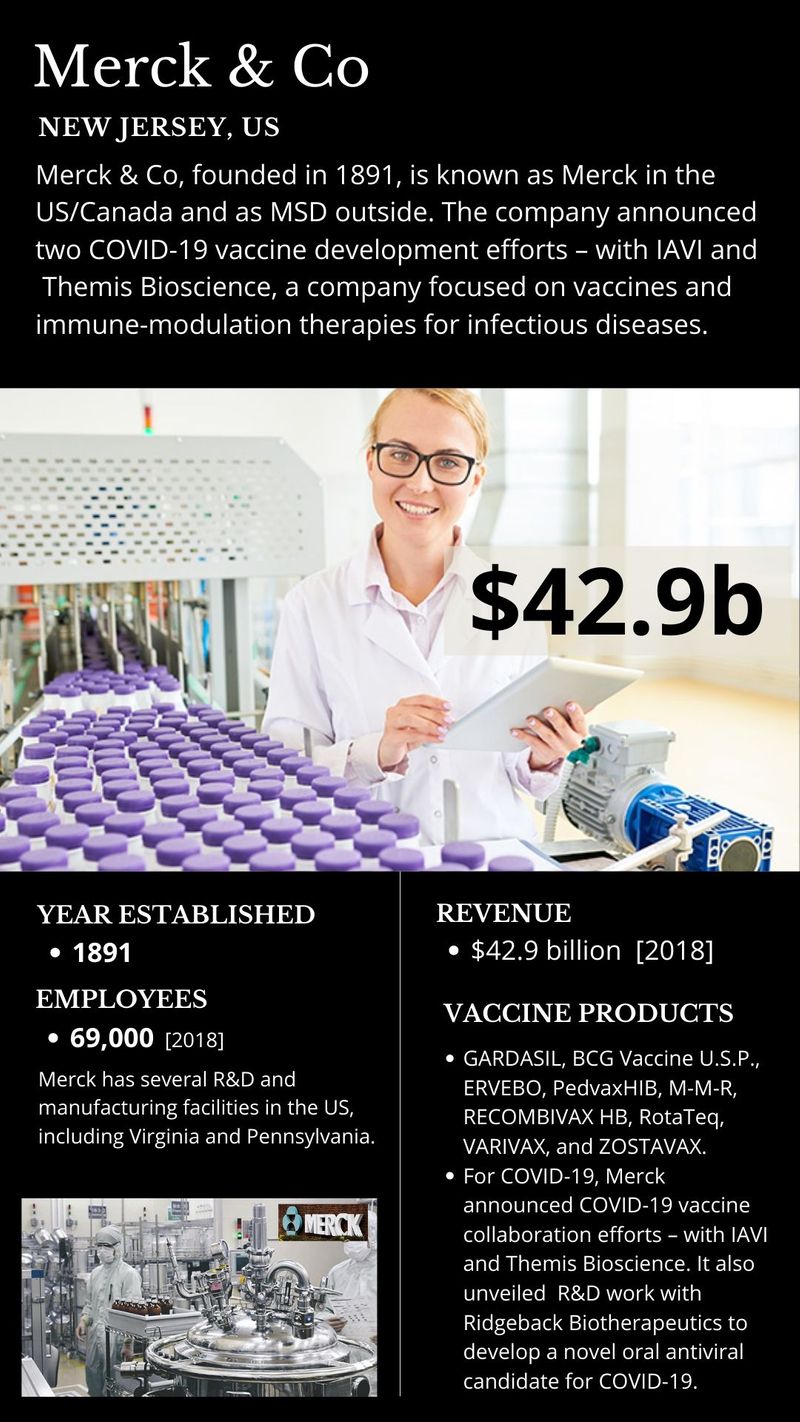

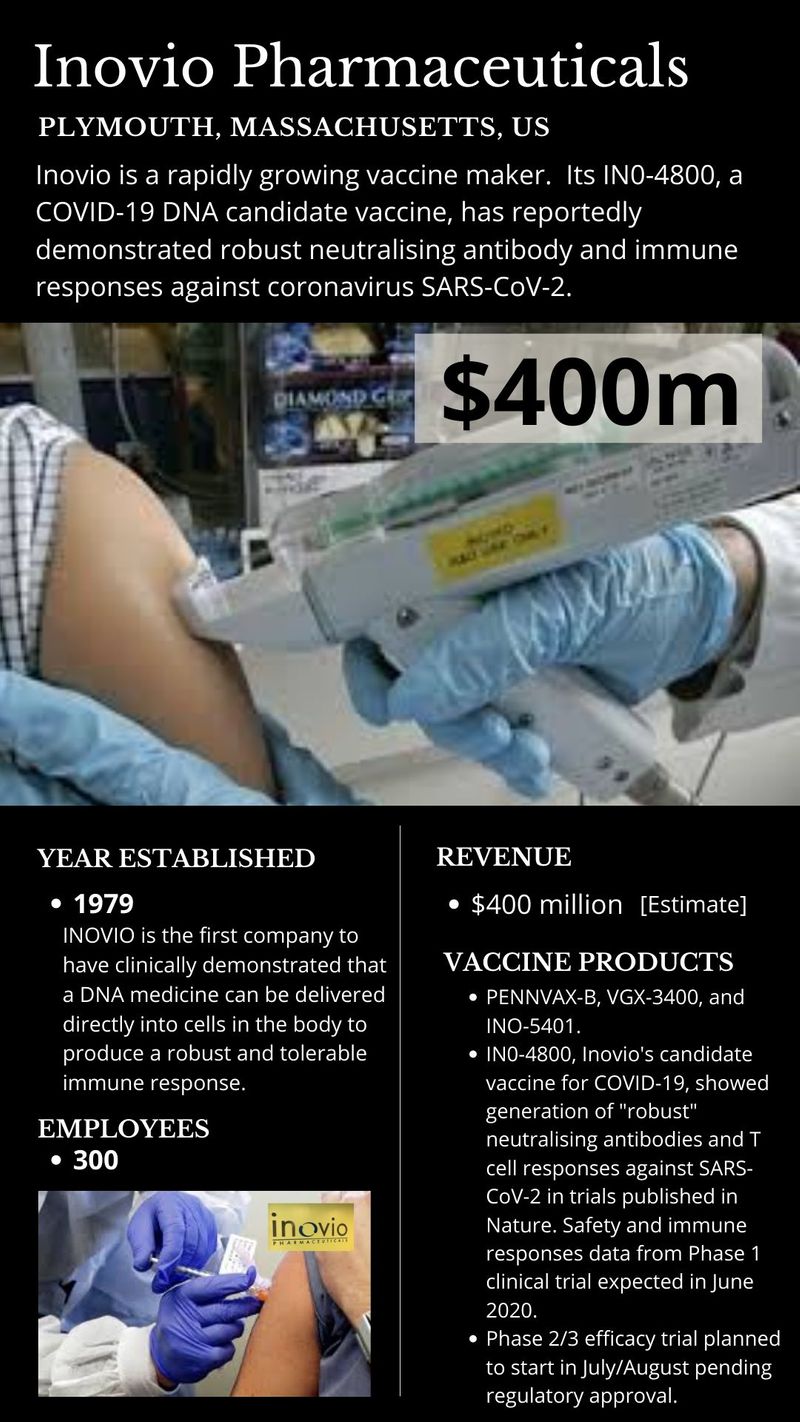

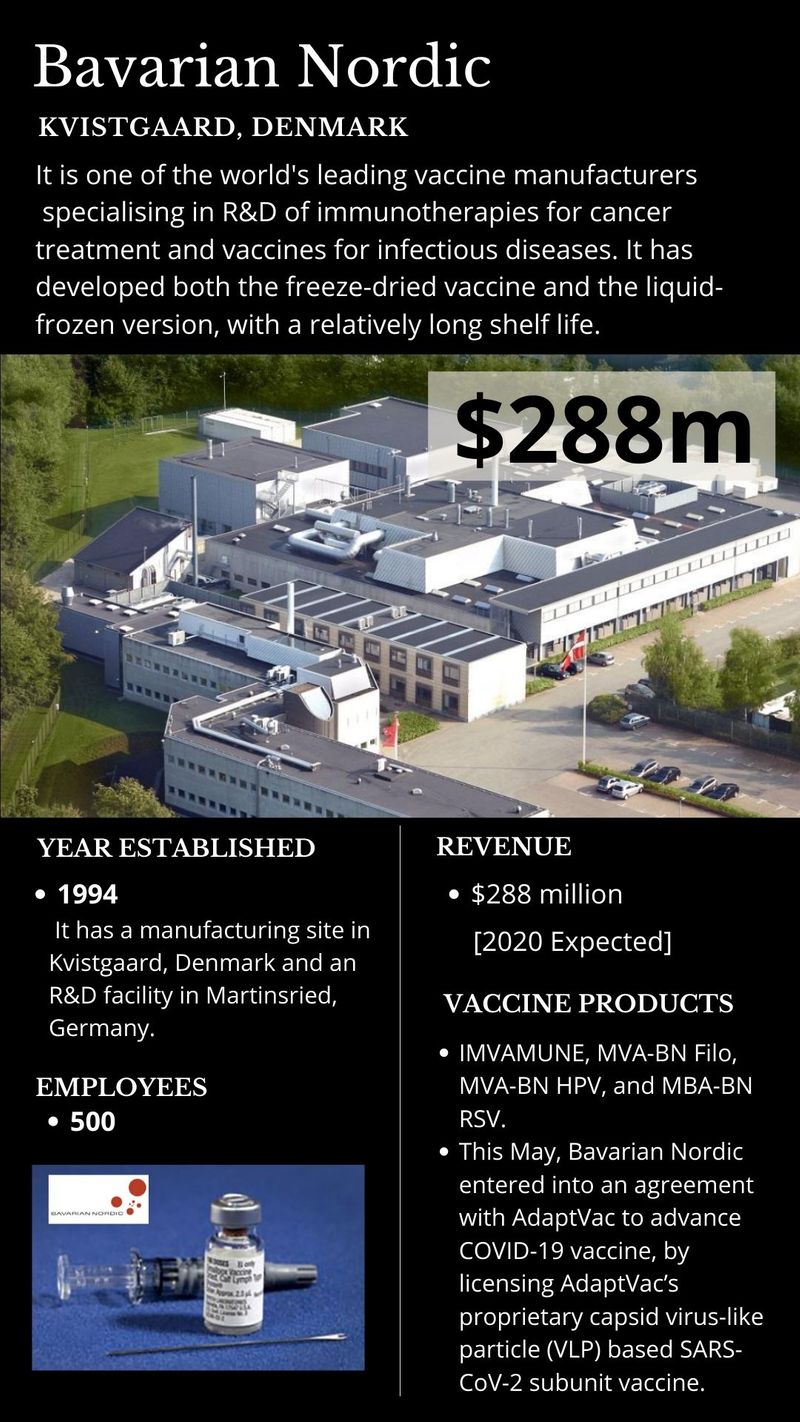

These are the companies at the forefront of COVID-19 vaccine development:

WHAT IS AN ADJUVANT?

An adjuvant is a pharmacological or immunological agent that improves the immune response of a vaccine.

Adjuvants may be added to a vaccine to boost the immune response to produce more antibodies and longer-lasting immunity, thus minimizing the dose of antigen needed.

The use of an adjuvant is important in a pandemic situation. For one, it may reduce the amount of vaccine protein required per dose, allowing more vaccine doses to be produced and therefore contributing to protect more people.

The combination of a protein-based antigen together with an adjuvant is well-established and used in a number of vaccines available today.

What is an mRNA vaccine?

Messenger RNA is a single-stranded RNA molecule that corresponds to the genetic sequence of a gene and is read by the ribosome in the process of producing a protein.

mRNA is created during the process of transcription, where the enzyme RNA polymerase converts genes into primary transcript mRNA.

Traditional vaccines are made up of small or inactivated/attenuated (or "killed") doses of the whole disease-causing organism, or the proteins that it produces, which are introduced into the body to provoke the immune system into mounting a response.

mRNA vaccines, in contrast, trick the body into producing some of the viral proteins itself. They work by using mRNA, or messenger RNA, which is the molecule that essentially puts DNA instructions into action.

Inside a cell, mRNA is used as a template to build a protein.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO)’s draft landscape of COVID-19 candidate vaccines, there are least 20 experimental mRNA vaccines in various stages of clinical development that use the messenger RNA (mRNA) platform to elicit an immune response against SARS-CoV-2. [Horizon EU Research and Innovation Magazine https://bit.ly/2X7lShR]

Most of these vaccines encode the spike protein of SARS-CoV2.

TAKEAWAYS

- There may be a sense of desperation, alongside high hopes and good wishes, instead of good science, behind the urge to push a COVID-19 vaccine out, regardless of the consequences.

- The whole purpose of clinical trials, is to find the right vaccine going forward. But even if all the vaccine trials fail, there are already proven therapies, including the Abu Dhabi stem cell therapy and convalescent plasma therapy.

- There's hope that the trials will find the right dose that causes the body to produce enough antibodies to fight COVID-19, but does not result in too many side effects.

- As different biopharma companies rush to get a jab developed as quickly as possible, the reality of vaccine development is that it can only be pushed at "warp-speed” so much.

- Amidst the global clamour and the media hype, vaccine trials have to move at the speed they move at, with the ups and downs.

- The trials need to run their full course. Data on safety and efficacy, including any adverse side effects, are important matters and should be shared — scrutinised, peer reviewed — and should guide the approval process.

- When a candidate vaccine is found, and approved, the next challenge is mass production. There are solutions to make it affordable and as widely available as possible, but it remains to be seen if that (affordable), indeed, will be the case.

- There's so much at stake in the sprint towards a COVID-19 antidote, but ultimately, it's the common good that counts.