The 100 greatest UK No 1 singles

The 100 greatest UK No 1s: No 8, The Prodigy – Firestarter

A surreal and terrifying mix of big-beat pyrotechnics, lyrical vitriol and tabloid outrage. ‘Ban This Sick Fire Record,’ squawked the Mail on Sunday – but it was much too late

by Chal RavensIt starts with a riff: not a distorted guitar but a contorted squeal from a twisted fairground. It’s a riff nonetheless, the instantly sticky sign of an unstoppable hit single. Firestarter was one of the biggest pop-cultural events of 1996 and by the end of the year the Prodigy were one of the world’s biggest bands. The Essex four-piece’s first No 1 was a flashpoint of teen angst, TV infamy, moral panic and tabloid outrage, carried aloft by big-beat pyrotechnics and a lethal barrage of lyrical vitriol. “Ban This Sick Fire Record,” squawked the Mail on Sunday – but it was much too late.

The Prodigy were already a dominant force in pop. All but one of their singles since 1991 had made the Top 15, including 1991’s Charly, the cartoon-sampling hit that famously “killed rave”, according to clubbers’ bible Mixmag. Liam Howlett, the band’s musical engine, was bored with cranking out rave hits to a formula and started experimenting with elements of hip-hop and rock on their second album, Music for the Jilted Generation. Now the Prodigy were ready to reintroduce themselves as stadium-sized heroes with The Fat of the Land, taking dance music deep into the moshpit while promoting dancer-cum-hypeman Keith Flint to songwriter and vocalist. As an opening salvo, Firestarter was flamboyant, surreal, terrifying – and, like all the best pop songs, totally novel.

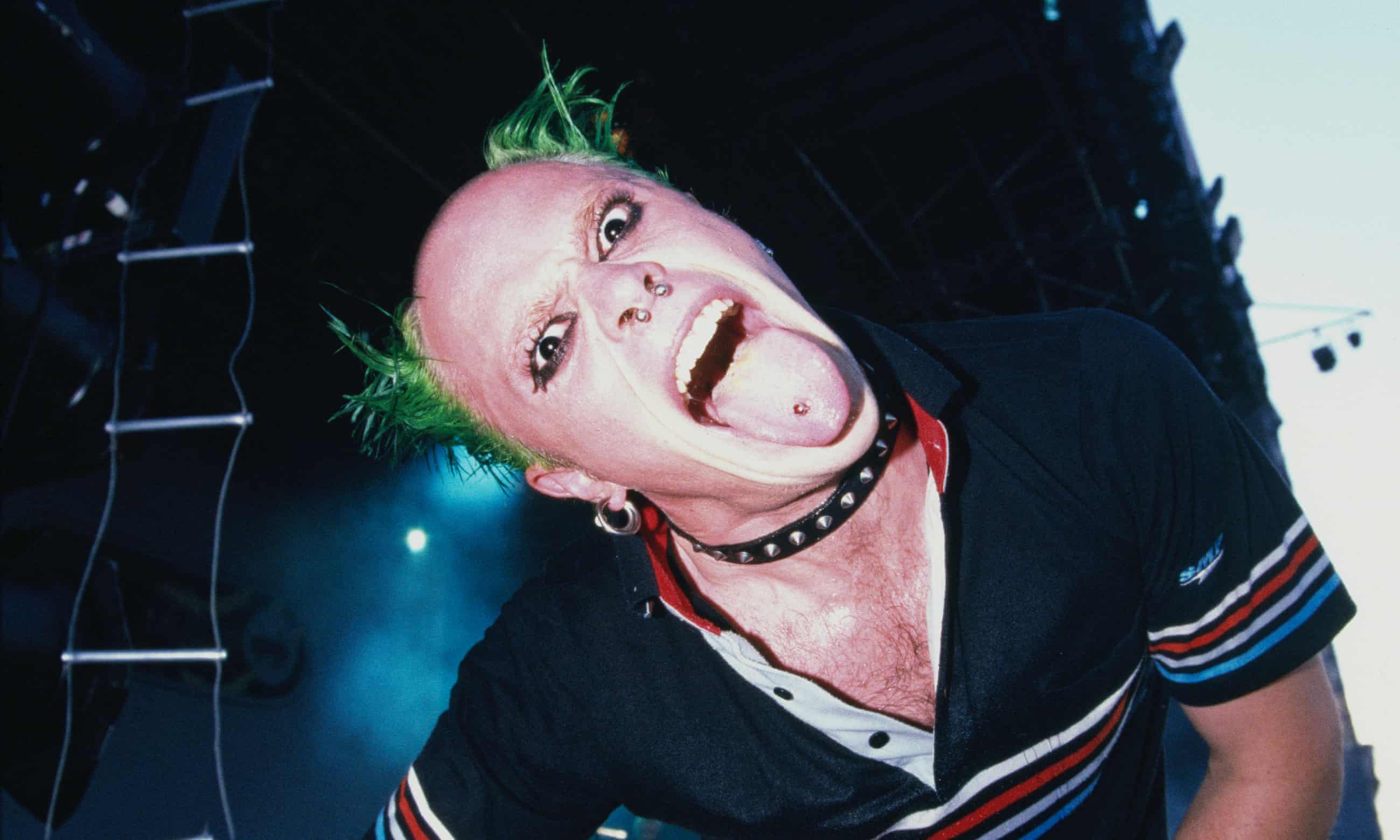

I have a faint recollection of watching Firestarter on Top of the Pops that week. The Prodigy didn’t want to perform, adamant that their anarchic live energy wouldn’t translate to the nation’s living rooms, so after Gina G and PJ & Duncan had done their thing, the BBC exposed millions of young minds to the video, depicting a diabolical figure in a reverse mohican twitching and gurning like a thing possessed. Too young to have any context for the music, I was transfixed but repelled, vaguely aware that this was something I probably shouldn’t be seeing.

That scuzzy black and white clip, filmed in a disused tube tunnel, was Firestarter’s second video, produced on a shoestring after the Prodigy had blown £100,000 on a hated first attempt. Flint flicks his pierced tongue at the camera, eyeballs glowing against his black eyeliner. The Prodigy came from the rave scene but this was more Marilyn Manson than Orbital, and Flint was a tortured rock god, snarling lyrics about mental anguish and self-harm: “I’m the self-inflicted mind detonator / I’m the bitch you hated, filth infatuated.”

The music press had been building them up as the “electronica” act that could finally crack the US, but the Prodigy didn’t see themselves in that lineage. They weren’t avant-garde like Aphex Twin and Autechre, and they weren’t purveyors of what rock writers liked to call “faceless techno bollocks”. Firestarter proved that the Prodigy was a squirming, sweating, fleshbound beast – the very opposite of the futuristic “braindance” coming from the electronic vanguard. It was pure boiling animus, doused in petrol and set off to ruin someone’s birthday party. “I have a philosophy that most of our music works on a really dumb level,” said Howlett, “which is the level most people understand.”

He imagined the Prodigy as a stadium-filling spectacle on a level with the rock bands such as Red Hot Chili Peppers and proto-nu-metallers Biohazard. “No glow sticks, no Vicks, people spitting everywhere – brilliant,” as Flint put it. They even brought in spiky-haired guitarist Gizz Butt, who’d played in early punk bands such as the Destructors and English Dogs. But where so many rock-historical references of the mid-90s felt like cosy nostalgia, Firestarter squeezed a final gob of spit from the spirit of 77 while becoming a legitimate stadium-sized alternative to Oasis. The Gallaghers so desperately wanted to be adored. The Prodigy didn’t give a toss. Howlett’s harsh sample collisions (a vocal scrap saying “hey”, from the Art of Noise’s Close to the Edit, and that squealing riff, pinched from the Breeders’ SOS) reflect his roots as a hip-hop DJ and breakdancer, but although he took production cues from righteous outfits including Rage Against the Machine and Public Enemy, he wasn’t interested in their message.

Firestarter doesn’t care about anything, nor does it contain a shred of self-regard. When Flint brought his “twisted” persona to life, he aligned himself with a 90s seam of edginess that brought us Fight Club, Tank Girl and Scream. It’s strange to imagine that we gawped and laughed. The decade’s flippant treatment of “insanity” is risible now, and especially tragic after Flint’s death in 2019. Journalists compared him to cartoon characters, but in those lyrics he is nothing but human. Firestarter is the worst of us, splattered on the kerb for all to see. “I wasn’t trying to say, ‘look at me, I’m Satan!’ But certainly I’m not nice,” Flint told Q magazine. “We’re everybody’s dark side.”