Short stories

Sorry for Your Trouble by Richard Ford review – stories of discontent

An uneven collection about marital discord and middle-aged disappointment from one of the grand figures of contemporary American fiction

by Erica WagnerThe final story in Richard Ford’s new collection is a tale of a marriage gone wrong – though something, we know, is salvaged from the wreckage. “Jonathan and Charlotte were divorced but had stayed friends,” “Second Language” begins. The marriage is a second attempt for both of them. Jonathan is a widower; Charlotte’s husband went off for a sailing trip and ended up making a new life without her. Confident Charlotte wasn’t too cut up; she meets Jonathan, who is pleasingly wealthy, when she’s selling him a fancy loft apartment.

One day a couple of years in, she realises “that she was not the most perfect person to be married to Jonathan Bell – even though she was married to him and liked him very much.” She breaks this to him not long after he’s had thyroid surgery – she “told Jonathan her news”, is the way Ford describes their conversation; the information is all in her control. Yet the reader knows he will not react too badly; the story is, for the most part, an elegant meditation on the currents of adult relationships, and how far any of us can escape our histories. It is the strongest piece in this uneven book, yet there is still a laziness of observation which also mars, for the most part, the other tales.

So we learn that Charlotte has two relationships after her divorce from her first husband: “One with an intense but too-diminutive brain surgeon, and one with a burly cop who wanted her to relocate to Staten Island.” Isn’t the stereotypical cop always burly – and always living on Staten Island? Women fare worse when it comes to this kind of slack description. Charlotte is “forty-four, a tall, easily smiling, lanky, intelligent beauty”. Is this how she thinks of herself? She had once been a model: “House hunters often did double takes when she hauled ‘those legs’ out of the car to present a property.” To whom do those quotation marks belong?

Charlotte, at least, is slender. More than once, across the entirety of this collection, the reader feels as if she’s in the presence of a speak-your-weight machine. In “Crossing”, Tom, a lawyer in the midst of finalising his divorce, observes a young woman: her “plump hands. The placid blue-eyed gaze of profound un-interest … The waist an equator, the legs large in a too-tight brown skirt that rode up revealingly.” In “The Run of Yourself”, Peter Boyce’s daughter Polly has “added more weight. She wore very tight blue jeans that weren’t helping.” Peter, like Jonathan in “Second Language”, is a widower; his wife Mae has been dead for two years. She was stricken with cancer but took her own life before the disease could kill her; she is described as “starkly pretty and thin” when dying of cancer.

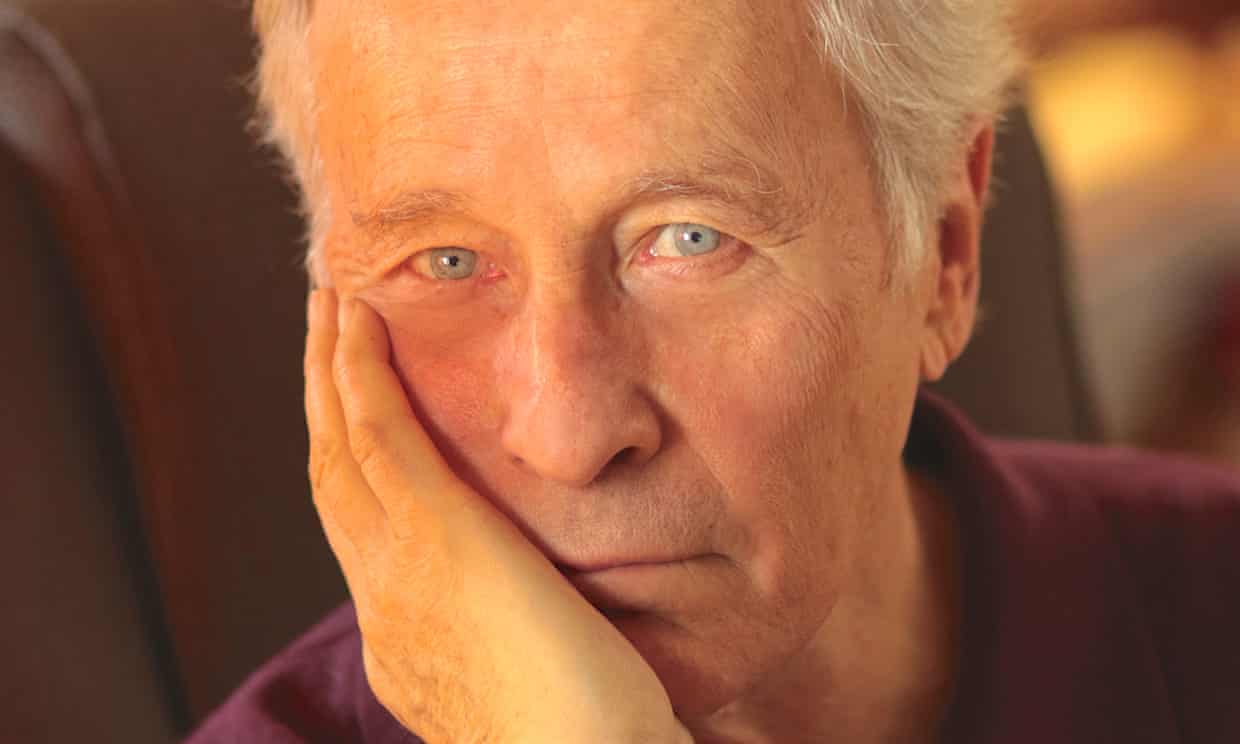

Ford is one of the grand figures of contemporary US literature: the Frank Bascombe trilogy of The Sportswriter, Independence Day and The Lay of the Land, published between the mid-1980s and the early years of this century, are landmark books. His work has always been distinguished by the precision of his observation and his thoughtful dissection of American life in the years following the end of the Vietnam war. His characters’ discontents – illness, divorce, estrangement – have always reflected the troubles of his native land.

But in Sorry for Your Trouble, that thoughtfulness is too often absent. Characters in stories are entitled to their perceptions of the world and those they observe. But the stories in this book come across as stale because, more often than not, the people in them seem imprisoned by a judgmental authorial voice. Most of these narratives concern the tribulations of middle-aged, middle-class men who find that life hasn’t quite worked out as they’d planned. In “Nothing to Declare” the narrator encounters an old love and has yet another unsatisfactory encounter with her; in “Displaced”, Henry recalls a youthful friendship gone wrong; in “Jimmy Green – 1992” Jimmy almost hooks up with a woman in Paris (“the flesh under her eyes was slightly wrinkled”) against the backdrop of Bill Clinton’s election to president. In earlier books Ford has painted these kinds of lives with wisdom and sensitivity; here, the characters’ resistance to emotional depth leaks out into the narrative. Henry’s friend Niall in “Displaced” is a working-class kid trying to hide the fact that he’s gay, but the broad brushstrokes tip him towards caricature rather than character.

What’s intriguing in “Second Language” is the way in which both Jonathan and Charlotte seem, to a certain extent, to elude their author: that’s what gives them a life beyond the page. The final tale here is the one that’s worth waiting for.

• Sorry for Your Trouble by Richard Ford is published by Bloomsbury (RRP £16.99). To order a copy go to guardianbookshop.com. Free UK p&p over £15