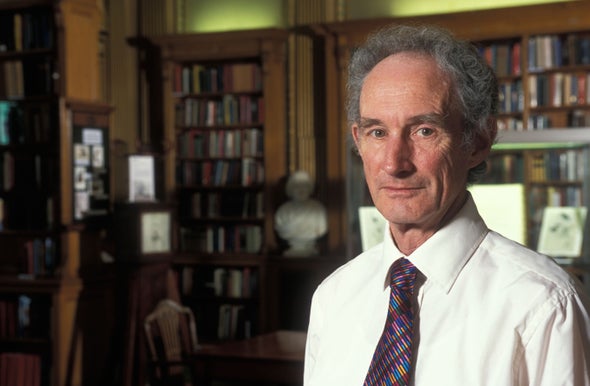

Robert May (1936–2020) and the Future of Scientific Research

He was utterly unpretentious, without guile or dissimulation, and candid to the point of tactlessness—qualities in unfortunately short supply today

by Edward TennerIt was a poignant coincidence. On May 11, the evening before Anthony Fauci, longtime director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and public health advisor to eight U.S. presidents, testified remotely to a Senate committee on the dangers of reopening the U.S. economy prematurely, the New York Times published an online obituary of Robert M. May, Lord May of Oxford. May was a founder of complexity theory who helped bring mathematical sophistication to the science of ecology, teaching at Princeton, Imperial College London and Oxford University, and serving as president of the Royal Society and chief science advisor of Tony Blair’s government.

May had a style unlike that of the quietly authoritative Fauci. He was brash, openly competitive, justifiably proud of his intellect and not shy about displaying it. But May was beloved because he remained utterly unpretentious, without guile or dissimulation, candid to the point of tactlessness. Paradoxically this most Australian of scientists probably could not have flourished in his native country, with its passion for putting ambitious virtuosi in their place—also known as “cutting down the tall poppies.” Hating pomp and circumstance, deploring American and British inequality, he nonetheless accepted a knighthood and then a peerage.

While Lord May drew the line at commissioning a (costly) coat of arms, he did relish the chance to speak out for scientific truth against political attacks, supporting climate science in warning of the effective of greenhouses gases on global warming—but also defending genetic engineering against the objections of organic food advocates. Even in the 1980s, he pointed out to me that conventional plant and animal breeding could be as deleterious as laboratory DNA tinkering. He was an ecologist committed to biodiversity—one of its preeminent theorists—but not a doctrinaire green.

The death of May and the increasing political polarization around the warnings of Fauci and other epidemiologists and virologists reveal the delicate position of high-level scientific advice in the 21st century. During the Cold War, physicists, chemists, and engineers—people like James Conant, George Kistiakowsky, Edward Purcell, Paul Doty and Detlev Bronk—prevailed, drawing on their experience in the Manhattan Project and other wartime service.

In that bygone American-Soviet postwar duopoly, science and scientists were one of the few communities that spanned the ideological chasm, at least after the death of Joseph Stalin in 1953. (Even a vicious anti-Semitic campaign of the dictator’s last years spared Jewish astrophysicist Yakov Zel’dovich, who played a key role in developing the Soviet hydrogen bomb.) Public scientists had a special role as advisors who could keep channels of communication open to help avoid inadvertent apocalyptic confrontation. They spoke a common language with Soviet scientific dissidents like Andrei Sakharov.

The demise of the U.S.S.R. and the explosion of new fields like genomics and artificial intelligence beginning in the 1980s and 1990s have made it far more difficult for any single person to give high-level advice on a range of subjects. Potential threats, from cyberattacks on power grids to designer plagues, proliferated in the post-Soviet era, demanding highly specialized expertise. Some scientists, like May, have a gift for identifying the best sources of such advice. His advantage was that so much of today’s science, from climate analysis to evaluation of financial systems, relies on the modeling tools with which May himself made his reputation.

Sadly, the effects of Alzheimer’s disease kept May from contributing to the debate on the novel coronavirus in early 2020. He was one of the few people who could have bridged epidemiological and economic models—one of his later papers was on the 2008 financial crisis and the complexity of derivative trading—to evaluate alternative strategies.

The open question now is the future of the “best science” approach of May, Fauci and others. So far, public opinion polls have revealed a deep and growing respect for such scientists. Still, there has been growing concern in the scientific community of a backlash as scientific recommendations are blamed for economic catastrophe. Experts once presented recommendations privately, however vigorously they lobbied for them. Today’s presidential science advisor needs to be not only a brilliant scientist and skilled bureaucratic infighter but a media personality in his or her own right.

Yet that role can appear to undermine the ultimate decision power of elected officials. Britain under Boris Johnson has no true successor to May under the Conservative John Major as well as the New Laborite Tony Blair, but a largely secret advisory committee—unlike the open if contentious relationship between Donald Trump and his advisors.

Perhaps May, with his mix of professional distinction (the Copley Medal he received from the Royal Society is even more exclusive than the Nobel Prize), versatility and unshakeable self-confidence, was the last of a breed. If so, it is unfortunate news for Britain, America and the world.