CoCo Bond Investors Face a Covid-19 Reckoning

The coronavirus pandemic is even starting to affect the highly specialized world of bank capital.

by Marcus AshworthThe Covid-19 pandemic is even starting to affect the highly specialized world of bank capital.

Lloyds Banking Group Plc, a large British lender, has just become the third European bank this year to do what was once unthinkable and decline to redeem an outstanding “CoCo” bond at its first call date. This form of hybrid debt — also known as additional tier 1 (or AT1) regulatory capital — is especially risky because the investor bears the losses if the bank fails, and it usually pays a generous interest rate.

Because of their special status, there had always been a tacit understanding — though not a legal obligation — that investors would be able to cash in the bonds at the first redemption date, if they so chose, at least with European CoCos. But that tradition looks to be well and truly over among the stronger banks.

Lloyds cited “extraordinary market challenges presented by Covid-19” as the reason to extend its own AT1s. With its dividend payments to equity holders suspended currently at the behest of the U.K. financial regulator, because of the coronavirus crisis, it would have looked rum indeed if the bank had cut its equity capital for the benefit of a small group of bondholders. This select bunch ought to have known the risk.

The financial savings for Lloyds are just as relevant. By retaining the 6.375% 750 million-euro ($824 million) CoCo, it will switch to paying a floating coupon just above 5%. If it had redeemed the AT1 and issued a replacement bond, it would have had to offer a higher coupon to reflect the current market, probably one above 7%.

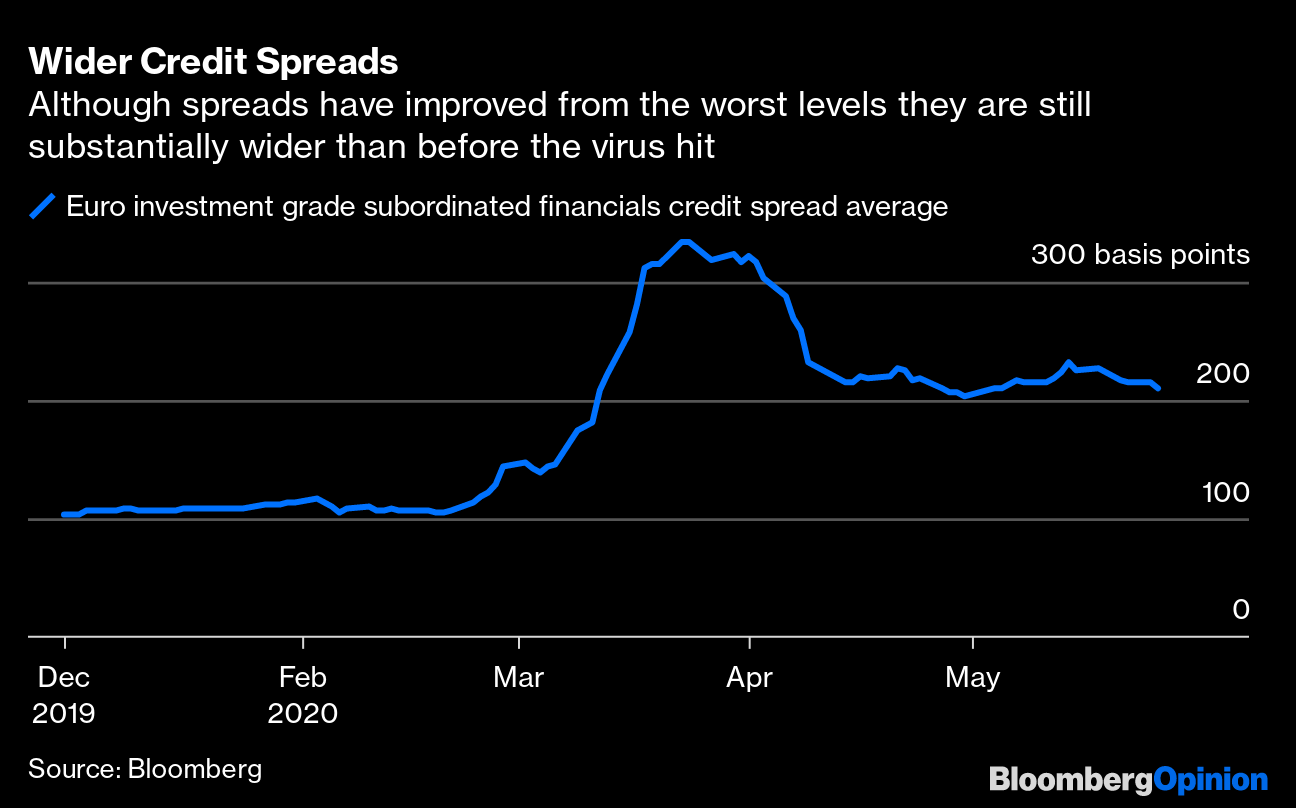

Lloyds has a solid Tier 1 capital base of 16.9%, so in normal times it would have been expected to keep its bond investors happy. But regulatory pressure and the increase in yields on risky debt during the current crisis has forced even the better capitalized banks to prioritize their financing costs.

Spain’s Banco Santander SA set the precedent last year of a blue-chip lender not redeeming its AT1 debt out of pure economic self-interest. That’s standard practice in the U.S. market, but Santander’s action caused a storm here in Europe. Germany’s Deutsche Bank AG and Aareal Bank AG have also skipped calls this year.

This Americanization of the European CoCo market looks like a trend. ABN Amro Bank NV and Royal Bank of Scotland Group Plc both have AT1 bonds with calls due this summer, and Barclays Plc is due later in the year. They may follow the Lloyds example and retain cheap AT1 capital raised at lower yields.

Banks have benefited hugely from AT1 issues as regulators count it as permanent equity (although it was almost always redeemed), meaning it counts toward capital buffers. And the cost is much lower for the issuer than true perpetual debt. Investors have been happy to play along as the yields far exceed those on bank debt with legally enforceable redemption dates.

The Lloyds move is a wake-up call for AT1 investors.

While the bigger banks’ CoCo bonds will probably still be popular, even if the call date is no longer guaranteed implicitly, the change might do more damage to weaker lenders. If investors no longer feel confident that their money will automatically be returned at the first redemption date, they’ll demand a higher return for the risk.

The CoCo market only reopened tentatively this month with a new Bank of Ireland Group Plc deal. The Irish lender did what Lloyds refused to do and redeemed its existing AT1 and reissued at a higher cost. At least it managed to keep its investors happy and on board.

This new separation between large stable banks being able to act according to their own economic advantage, while smaller rivals have to offer chunkier premiums, is a worry for the health of the financial system. It ought to be an urgent matter for consideration by European regulators. Forcing the strong banks to keep capital has consequences for their less illustrious peers.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

To contact the author of this story:

Marcus Ashworth at mashworth4@bloomberg.net

To contact the editor responsible for this story:

James Boxell at jboxell@bloomberg.net