Reading the Blueprints for Our Future After the Virus

by Brian MerchantFor more information on the novel coronavirus and Covid-19, visit cdc.gov.

Works from the Bible to ‘Epidemics and Society’ to ‘The Age of Surveillance Capitalism’ help predict our post-pandemic future

According to the Stanford historian Walter Scheidel, there have been only four phenomena in the course of modern human history that have ever rendered our societies more equal in any sustainable fashion. Three of the four involve violent, human-instigated conflicts against other humans — war, bloody revolution, and state failure. The fourth is pandemic.

“For thousands of years, civilization did not lend itself to peaceful equalization,” Scheidel writes in 2017’s The Great Leveler: Violence and the History of Inequality from the Stone Age to the Twenty-First Century. “This was as true of Pharaonic Egypt as it was of Victorian England, as true of the Roman Empire as of the United States. Violent shocks were of the paramount importance in disrupting the established order, in compressing the distribution of income and wealth, in narrowing the gap between rich and poor.”

And one particular kind of shock, historically, has the edge. “In the past, plague, smallpox, and measles ravaged whole continents more forcefully than even the largest armies or most fervent revolutionaries could hope to do,” Scheidel writes. For one thing, in plagues like the Black Death, the poor could requisition the goods and property of the newly deceased rich. More significantly, willing and able laborers were suddenly very valuable, so they could secure better terms — though not always without conflict. “Elites commonly attempted to preserve existing arrangements through fiat and force,” Scheidel writes, “but often failed to hold equalizing market forces in check.” Labor usually triumphed, and the playing field was leveled.

The historian raises the question: Wasn’t there something, anything else — worker movements? political reform? — in the annals of history that lessened inequality without mass death? “If we think of leveling on a large scale, the answer must be no,” Scheidel writes. “Democracy,” he adds, “does not of itself mitigate inequality.” But it might when paired with a pandemic.

Unlike the Black Death, which killed tens of millions and often decimated a quarter or even half of the populations of the cities it visited, the Covid-19 crisis is unlikely to immediately and radically reconfigure entrenched power balances. But the extreme stresses it places on our societies will open up spaces for transformation nonetheless. Such as, perhaps, rendering equality more feasible.

I know this, because I have spent as much of my pandemic quarantine as possible…reading everything I could get my hands on about the past, present, and future of pandemics.

“The more severe and prolonged the crisis, the more likely this is to happen,” Scheidel told me recently. “More state intervention in the private sector, socialized health care, worker protection, public works programs, funded in part by more progressive or higher taxation. Despite the pervasive rhetoric of ‘this is like a war,’ the New Deal looks like a better analogy.”

That may seem optimistic from where we’re sitting, which is somewhere in quarantine for the second or third or fourth or whatever month, watching the federal response sputter haplessly on, the economy collapse, and the death toll continue to climb. But we do have a long history of responding to crises by fighting for reforms, displaying scientific ingenuity, and building more durable institutions and communities. Unfortunately, we also have a long history of watching such crises beget new authoritarian modes of control, widespread surveillance, and systematic repression.

I know this, because I have spent as much of my pandemic quarantine as possible — whenever I’m not staring into the dark void of Twitter, chasing screaming toddlers down the hallway, or fretting over vulnerable friends and family members — reading everything I could get my hands on about the past, present, and future of pandemics. About plagues real and imagined. About how prolonged outbreaks and catastrophes reshape society. About who tries to profit, and who tends to triumph.

This turned out to be a strange undertaking in a moment when we are all are more wired than ever to a seemingly inescapable shared omnipresent, when we are all subjected to a deluge of news and notifications and updates that rattle our nerves 28 hours a day, nerves that fray and twitch until we are fully and finally depleted of dopamine and sent to bed as withered, addled husks. It is a weird time to read long works of scholarship and fiction. But pandemics have shaped human history more profoundly than any phenomena besides war, and if we want to get a sense of how we might tip the scales away from the fascistic pitfalls of the past — and toward a more promising post-pandemic future — it’s probably worth hitting the books.

So, I read. As ambulance sirens whined in the background, I read the unsettlingly prescient Epidemics and Society: From Black Death to the Present, by the Yale medical historian Frank M. Snowden, which was published just last October — two months before the first Covid-19 cases were reported. Then I read Severance, by Ling Ma, one of the buzzy “plague reads” that drew attention online thanks to its prescient treatment of disease, supply chains, and the consumer condition, and had my faith in modern humanity shaken. I reread the existentialist classic The Plague, by Albert Camus, and had my faith restored. I read The Great Leveler — the parts about pandemic, anyway — and The Great Influenza, by John Barry. I read Edgar Allan Poe and Mary Shelley and Jack London.

My aim was to turn to history, political theory, and speculative fiction to attempt to synthesize some kind of a blueprint of where this mess might take us in the future: a modern pandemic reading list of sorts. That meant tackling the nonfiction and plague novels. It meant reading science fiction that tried to imagine post- or co-pandemic futures: from Margaret Atwood’s Oryx and Crake to Emily St. John Mandel’s Station Eleven, to Stephen King’s The Stand. I read the Doomsday Book, by Connie Willis, and Ammonite, by Nicola Griffith. I also wanted to revisit books that examine how power responds to sustained crisis — so it meant returning to Naomi Klein’s The Shock Doctrine, David Noble’s Progress Without People, Shoshana Zuboff’s The Age of Surveillance Capitalism, and Rebecca Solnit’s A Paradise Built in Hell. On that note, it meant going back to the Bible.

It’s right there in Genesis, after all, wherein our humanity-defining vulnerability to disease is handed down as a punishment for original sin. When God expels Adam and Eve from Eden, he “ordained that they suffer disease, hard work, pain during childbirth, and finally death,” Snowden writes in Epidemics and Society; “Diseases, in other words, were the ‘wages of sin.’” The Bible casts pestilence as we frequently amoral humans’ own fault — at once burdening us with the guilt and blame for bringing mass death upon ourselves and hardwiring disease into our future. And sure enough, the future would be full of desperate attempts to pay back those wages.

Because, if you take the macro view, a pandemic is just about always on the cusp of happening. We have spent much more of our history anxiously managing a coexistence with a constant specter of plague than we have in the luxury of our placid pre-Covid condition, that is, mostly ignorant to the reality that infectious disease could cut down our societies with relative ease. Pandemic, and especially our responses to it, has defined us as a species, as a global community. It may feel novel, but it is not — it had just not yet been mediated on Twitter or commiserated on over Zoom in a shared experience felt at once by billions of worried homestuck potential infectees.

As Camus put it, “everybody knows that pestilences have a way of recurring in the world; yet somehow we find it hard to believe in ones that crash down on our heads from a blue sky.”

Now that we no longer find it so hard to believe, here’s what we might know about what happens next.

How plagues built public health, inspired surveillance, and forged the modern state

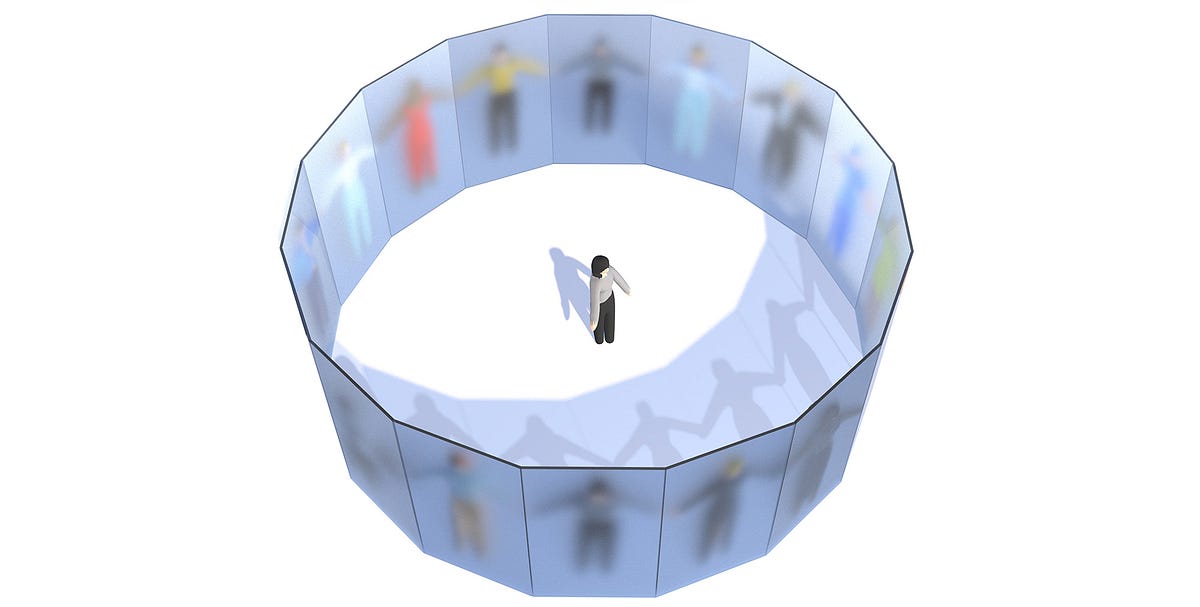

The coronavirus will at the very least be the farthest-reaching and most impactful pandemic in a generation, and, if history is any guide, it will radically reorient the way societies approach public health, surveillance, and statecraft. Pandemics, in some regard, have helped give rise to the modern state itself.

And the plague looms largest, and maybe most profoundly. There are three major plague pandemics in modern history, all caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis, each responsible for millions to tens of millions of deaths. The second is probably the most notorious of the three, as it began with the Black Death, the bubonic plague that ripped through Europe in the 1340s and became a keystone in shaping modern society’s response to public health crises. The plague is believed to have originated in China, and was spread by fleas riding on rats, which in turn boarded human vessels traveling around the world. Italian city-states like Venice and Genoa, which served as global trade hubs of the day, were a crucial entry point for the plague-carrying rats making their way into Europe.

To halt the spread of a fast-moving virus, definitive, rapid action and mass behavior change is necessary.

Before the plague, Venice and Genoa were loosely governed city-states with no central body empowered to enact aggressive measures like, say, placing the sick in enforced quarantine. After the plague, that changed. As the Yale historian of medicine Frank M. Snowden explains in Epidemics and Society: From Black Death to the Present, the term “quarantine” was coined to describe the 40 days that a sailor would be moved, by newly authorized agents of the state, into a pesthouse, or lazaretto, while waiting to ensure he was not carrying the plague. (The number 40 held religious significance — Christ spent 40 days in the desert resisting temptation.) These lazarettos were innovations, too. Medical science of the day did not yet understand that the plague was carried in pests, but 40 days happened to be long enough for the fleas to die off and prevent the spread of the disease. Prior to the Black Death, quarantine measures had never really been attempted at scale before.

Snowden’s book is blunt, informative, and deeply contextualizing — required reading for anyone interested in understanding a pandemic’s capacity to reorganize social structures.

“Plague was also significant because it gave rise to a critically important societal response: the development of public health,” he writes. “Bubonic plague inspired the first and most draconian form of public health policy designed to protect populations and contain the spread of a terrible disease, that is, various forms of enforced isolation of the sick.” Officials and conscripts were empowered to administer quarantine, send doctors to the sick houses, and coordinate the disaster response once the pandemic was underway. The lazarettos, pioneered in Venice, were mimicked and adopted around Europe.

“They marked a vast extension of state power into spheres of human life that had never before been subject to political authority,” Snowden writes. “They justified control over the economy and the movement of people; they authorized surveillance and forcible detention; and they sanctioned the invasion of homes and the extinction of civil liberties… The campaign against plague marked a moment in the emergence of absolutism, and more generally, it promoted an accretion of the power and legitimation of the modern state.”

Elsewhere, military cordons were put into place to guard against infiltration. The Habsburg Empire set up a vast line of armed soldiers to prevent plague-addled goods from crossing from Turkey into Europe. The so-called Austrian cordon “was a great, permanent line of troops stretching across the Balkan peninsula to implement a novel imperial instrument,” writes Snowden. And thus, the military border was born. The troops would intercept and inspect any goods or travelers wishing to pass. This, according to Snowden, constituted “perhaps the most impressive public health effort of the modern period.” It was staffed continuously, for over 150 years, from 1710 to 1871, until it was shut down at the behest of liberals and economists, who had assailed it for being oppressive to human rights and trade.

That these instruments of state surveillance and control proved so durable should give us ample reason to take a long hard look at the tools being adopted today to combat and track Covid-19 — those deemed successful could remain in place long after the virus, at an obvious cost to civil liberties.

Governments using crises to justify expanding surveillance power is no novel concept, of course. But it’s disconcerting just how fast the current pandemic has inspired nations around the world (at least 30, including the U.S., at last count) to embrace privacy-invading tracking measures in the name of tracing the virus and enforcing social distancing. Some governments require citizens and visitors to download apps when they arrive at points of entry; others have instituted mass cellphone tracking; and still others are using drones to determine if citizens might be infected and to police citizen habits. Google and Apple, two of the world’s largest and most influential corporations, have teamed up to launch a contact-tracing app. In the U.S., the Federal Emergency Management Agency is directing states to share public health data with the secretive big data analytics firm Palantir, blurring lines between which patient data can and should be kept private.

It’s a constant tension throughout the history of pandemic intervention: to halt the spread of a fast-moving virus, definitive, rapid action and mass behavior change is necessary. There are few greater and more tempting opportunities for authoritarian impulses to take hold. Rapid, surveillance-enabled quarantine — as seen recently in South Korea and China — may save lives. It may also help entrench the normalcy of invasive spying on citizens. The deep anxieties over this tension have become a reliable fixture of pop culture; in Stephen King’s The Stand, the military simultaneously disseminates disinformation about a deadly strain of influenza and enforces a repressive, if impotent, quarantine. The hit 1995 film Outbreak hyperbolizes the military’s draconian response to a deadly virus: In the film, not only is the state willing to bomb infected villages and towns, but it would seek to transform the disease into a bioweapon to exert further control rather than support scientists working methodically to trace and contain the disease.

“A hundred disparate historical trends converge on a single, modest act — some unknown person unscrews the handle of a pump on a side street in a bustling city.”

And yet, countless truly valuable public health innovations truly are borne in times of crisis. The invention of the vaccine, for instance, came after Edward Jenner observed that people who contracted cowpox became immune to smallpox, too, mitigating what was then the deadliest disease in Europe. Vaccines are obviously now routine and vital tools in fighting and abolishing disease, regardless of whether a pandemic is underway; a modern society is nearly unimaginable without them.

In The Ghost Map, Steven Johnson’s nonfiction account about London’s deadliest cholera outbreak, we’re given a window into the mechanics of such innovation in public health in plague times — through the work of a physician named John Snow, who would help transform not just public health but the science of urban planning. Snow had become convinced that cholera was being transmitted not by miasma, as the prevalent belief of the day held, but through water — and in particular, by one polluted water pump on Broad Street. He used public data to map infections around the neighborhood and to build his case. With the help of a local reverend, Snow convinced the city to take the water pump handle down.

“The removal of the pump handle was a historical turning point, and not just because it marked the end of London’s most explosive outbreak,” Johnson writes. “A hundred disparate historical trends converge on a single, modest act — some unknown person unscrews the handle of a pump on a side street in a bustling city — and in the years and decades that follow, a thousand changes ripple out from that simple act.” That’s because, for perhaps the first time, a scientific case for making a public health decision, based on public data, had been rendered in the time of crisis. “The decision to remove the handle was not based on… watered-down medieval humorology; it was based on a methodical survey of the actual social patterns of the epidemic, confirming predictions put forward by an underlying theory of the disease’s effect on the human body,” Johnson writes. “For the first time, the V. cholerae’s growing dominion over the city would be challenged by reason, not superstition.”

This, Johnson argues, led to a novel approach of combating disease in densely populated places — one that would eventually lead to a proactive, science-based bureaucratic system that would render cities safe and healthy enough to finally kill the stigma that they were cesspools of grime and disease. That, in turn, led to mass urban migration and inspired the practice of incorporating data and proactive analysis into urban design on many other fronts. In other words, according to Johnson, London’s fight against cholera helped give rise to the modern city.

Unpredictable trends will surely ripple out of the frenzy of research around the coronavirus crisis. Researchers have already used A.I. to locate promising new treatments for Covid-19; vaccines and treatments are being fast-tracked at unprecedented rates; and medical scientists, technologists, and state officials are sharing data on scales not previously seen. If plagues and pandemic helped entrench state power, granting it the ability to enact physical quarantines and military cordons in the name of public health, the frontier we should be watching now is digital; malleable and vulnerable as it is to data-hoovering public-private partnerships and unscrupulous mass data collection.

A key to ensuring that digital systems like contact tracing apps do not lead to corporate profiteering or privacy invasion is insisting that these innovations are managed by transparent, democratic, and accountable agencies, argues Shoshana Zuboff, author of The Age of Surveillance Capitalism.

“Apps to control the spread of the virus? They should be managed by public institutions and become mandatory like vaccines,” Zuboff recently told the Italian newspaper La Republica. “We are going through a dark period, but neither for Europe nor for the United States is this the first time. After the Great Depression, America recovered, creating new institutions and a new social pact. It’s what we have to do today.”

It will be a formidable challenge to accommodate any useful new tools invented in the wake of this crisis, ensuring they’re commonly held while resisting corona-inspired autocratic creep — and using this rupture to argue for the transfer of digital power into the public sphere. Fortunately, crises offer space for transformation, too.

“We have an extraordinary opportunity to take control of the world of information and data aimed at public well-being and the defense of our values,” Zuboff said. “This is not the moment for catastrophism, this is the moment in which we can decide the basis of our future.”

If that seems optimistic, consider that pandemics also hold the power to imbue new and extant public institutions that act transparently with trust and good faith, too. Take John Barry’s briskly written book, The Great Influenza, which details the gruesome history of the 1918 Spanish Flu, a pandemic that rivals the Black Death in its astonishing casualty count. (As many as 100 million people perished worldwide.) Barry recently wrote in the New York Times that there was a single “most important lesson of 1918, one that all the working groups on pandemic planning agreed upon: Tell the truth. That instruction is built into the federal pandemic preparedness plans and the plan for every state and territory.” He continues:

In 1918, pressured to maintain wartime morale, neither national nor local government officials told the truth. The disease was called “Spanish flu,” and one national public-health leader said, “This is ordinary influenza by another name.” Most local health commissioners followed that lead. Newspapers echoed them. After Philadelphia began digging mass graves; closed schools, saloons and theaters; and banned public gatherings, one newspaper even wrote: ‘This is not a public health measure. There is no cause for alarm.’

Trust in authority disintegrated, and at its core, society is based on trust. Not knowing whom or what to believe, people also lost trust in one another. They became alienated, isolated. Intimacy was destroyed. ‘You had no school life, you had no church life, you had nothing,’ a survivor recalled. ‘People were afraid to kiss one another, people were afraid to eat with one another.’ Some people actually starved to death because no one would deliver food to them.

Society frayed so rapidly during the Spanish Flu that the scientist who was in charge of the American armed forces’ division of communicable disease worried that if the pandemic continued accelerating for a few more weeks, ‘civilization could easily disappear from the face of the earth.’

On its face, this would bode ill for our current situation — the Trump administration has constantly lied, misspoke, deflected, and otherwise muddied the waters about its response to the outbreak. But in 1918, some states, like Missouri, acted early, truthfully, and aggressively and earned the backing and faith of their populace. Today, Barry believes public trust in institutions will not be shattered — and instead, that there lies the promise of hope, of trust in open, accountable government bodies.

“The White House, Trump, and his personal staff, clearly misled the public and continue to mislead the public,” Barry told OneZero. “That’s not helpful, but the negatives attach largely to Trump personally. I agree that the public health community has generally done very, very well. Governors have varied. I actually think all this may restore some trust in government, despite the White House, because it demonstrates why we need a government — to make us safer.”

“If the pandemic continued accelerating for a few more weeks, ‘civilization could easily disappear from the face of the earth.’”

Consolidation, automation, and Amazonification

Outside the public sphere, a familiar threat has taken shape: That a host of powerful corporate actors are using the pandemic-stricken environment to their advantage amid the chaos. These companies have fought for favorable terms and government cash injections, to move their operations further into the public sphere, and consolidate power while the forces that might resist are preoccupied. It’s a tactic and impulse that the activist and author Naomi Klein calls the shock doctrine, as coined in her 2009 book of the same name — a book that saw an acute spike in interest as these phenomena began to unfold — and it’s a force that may do much to shape the crippled post-pandemic economy.

The total economic damage of the virus will surely be devastating. Unemployment claims are already at record levels. Restaurants, small businesses, and bars are closing, some permanently. Some projections say that a full one-third of Americans will be unemployed after the pandemic — and many more will be underemployed, underpaid, and reliant on gig work. If small businesses do not recover, many more will turn to Uber, Lyft, InstaCart, DoorDash, and Amazon for platform-based work. Amazon, for example, is hiring masses of workers, and scrimping on worker protections to maximize profits. The company is also using the confusion of the pandemic to fire dissenting workers, implement policies that further disadvantage third-party vendors who rely on its platform, and consolidate its power over the retail market. Early on in the pandemic, I looked at how the pandemic would speed up the already brisk Amazonification of the economy, and it’s accelerating in part thanks to shock doctrine tactics.

Klein calls this “disaster capitalism,” and she defines it as “orchestrated raids on the public sphere in the wake of catastrophic events, combined with the treatment of disasters as exciting market opportunities.” That’s an apt assessment of what’s unfolding now in many sectors, perhaps most pointedly in the tech sector. Klein excavated her doctrine directly from the words of Milton Friedman, one of the most powerful conservative economists of the 20th Century. “In one of his most influential essays,” Klein writes, “Friedman articulated contemporary capitalism’s core tactical nostrum, what I have come to understand as the shock doctrine. He observed that ‘only a crisis — actual or perceived — produces real change. When that crisis occurs, the actions that are taken depend on the ideas that are lying around.’”

Right now, the ideas that are lying around involve amping up digital surveillance, remote privatized education, home automation, and a wider role for tech companies in our private spaces, as Klein argued in an Intercept piece examining how former Google CEO Eric Schmidt was using a “Pandemic Shock Doctrine” to expand tech profits through a partnership with New York State.

After the virus fades, it will give way to a world where tech and platform-based companies are more primed than ever to exploit what Mary L. Gray and Siddharth Suri, authors of Ghost Work: How to Stop Silicon Valley from Building a New Global Underclass call “ghost work;” temporary, precarious work performed by real people who are subsumed into a technological system that renders them invisible. Ghost work is alluring both because it gives tech companies an excuse to reduce labor costs — gig workers finding work through a platform do not currently qualify as employees, who would require benefits and worker protections — and because the faceless, exploited workers help lend their platforms the sense that it’s automated, easy, and high-tech.

“On-demand labor platforms offer today’s online business a combination of human labor and A.I., creating a massive, hidden pool of people available for ghost work,” the authors write. Gig work has been eroding the bonds of traditional employment for over a decade now, and the virus will only accelerate the trend.

“I believe that the Covid crisis will accelerate the rise of ghost work as more companies will need people doing the kinds of information service work that we describe — training A.I. as more businesses look for software solutions to a host of job functions and human-in-a-loop services, like telehealth and sales that interweave people and computation,” Gray wrote me in an email. “But keep in mind that ghost work conditions also describe what every app-based delivery person is experiencing: constantly having to seek tasks and projects, and working for many ‘task-masters.’”

Furthermore, as small businesses, local restaurants, and bars close, the platform companies will be there to scoop up the desperate, newly unemployed precariat.

“The dismantling of employment is a deep, fundamental transformation of the nature of work,” the authors write in Ghost Work. “Traditional full-time employment is no longer the rule in the United States. It used to be that a worker could spend decades showing up day after day to the same office, building a career, with the expectation of getting steady pay, health care, sick leave, and retirement benefits in return. Now, centuries of global reforms, from child labor laws to workplace safety guidelines, are being unraveled.” As of 2019, the authors note, only 52% of today’s employers sponsor workplace benefits at all. And that number is about to nosedive.

Of course, the post-pandemic world of precarious platform work was decades in the making — the crisis may simply accelerate the shift. “The information highway is barely under construction, the virtual workplace still largely experimental, but their consequences are readily predictable in the light of recent history,” David Noble wrote in Progress Without People. “In the wake of five decades of information revolution, people are now working longer hours, under worsening conditions, with greater anxiety and stress, less skills, less security, less power, less benefits, and less pay. Information technology has clearly been developed… to deskill, discipline, and displace human labor in a global speed up of unprecedented proportions. Those still working are the lucky ones.” That was in 1995.

Noble recognized that technologies touted as labor-saving or more efficient were often most useful in mutating salaried work into ghost work, increasing profits for the firm, and serving as an instrument of control over its workers — he did not live to see the rise of Uber and InstaCart, but that’s basically what their platforms have done. Noble was describing the march toward automation that was promoted by corporations through the 20th century, largely in the manufacturing sector, that helped dislocate good jobs and speed the rise of informal work. It’s a point that is again freshly relevant. Firms are again talking at length about implementing automation to fill the void left by furloughed or sickened workers in the wake of the virus, and robotics and automation software companies proclaim that business is brisk.

Information technology has clearly been developed… to deskill, discipline, and displace human labor in a global speed up of unprecedented proportions. Those still working are the lucky ones.” That was in 1995.

The pandemic has delivered a violent shock to societies around the globe, and even though the federal stimulus in the U.S. was directed predominantly toward bailing out corporations, the longer-lasting effects may favor the middle class. Workers are already recognizing their value and organizing for better conditions — and, in many cases, winning. The coronavirus may serve as a springboard for workers, who, recognizing their collective power, to organize in greater numbers — some believe the biggest labor movement the nation’s seen in decades is on the horizon.

Also on the horizon, maybe: Some form of a universal basic income. The War on Normal People author and former presidential candidate Andrew Yang helped mainstream the modern concept of UBI, which is in the running for “top idea lying around” in the whole of the pandemic. On the trail and in his book, Yang argued that UBI would be necessary to help Americans survive the coming surge of automation-driven job loss. Now, he’s pushing it as a disaster relief mechanism, and it is being instituted as a short-term policy solution in nations around the world and has almost certainly entered the conversation as a long-term fixture of our policy debate.

In his book, Yang writes that he would institute a $12,000 a year annual guaranteed income, which he would call “The Freedom Dividend,” tailored to automatically elevate everyone just above the $11,770 poverty line. “A universal basic income is a version of Social Security where all citizens receive a set amount of money per month independent of their work status or income,” he writes. Yang points out that while today, “people tend to associate universal basic income with technology utopians,” the idea has been proposed by everyone from Thomas Paine to Martin Luther King Jr. to, yes, Milton Friedman.

Before the virus, UBI was mostly considered wonky, unworkable, or left-field — but now, the New York Times writes that “proposals similar to Mr. Yang’s signature policy prescription gained wide, bipartisan approval.” Even the conservative Financial Times proclaimed that, when it comes to fixing the pandemic-strained social contract, “Policies until recently considered eccentric, such as basic income and wealth taxes, will have to be in the mix.” After the virus, expect to hear a lot more about UBI.

While no-strings cash grants may sound good, even radical, there’s reason to be wary. If it’s supplemental to state benefits, it could be a worthy support mechanism. But in his book, Yang also imagines that his Freedom Dividend “would replace the vast majority of existing welfare programs.” Such a scenario would, in the long run, risk merely shifting the deck chairs on the Titanic, or worse, instate a modern iteration of feudalism.

Better, the virus may shock open new spaces of possibility. Just as it makes clear that delivery drivers and food distributors deserve the protections of full employment, it also reveals that some essential elements of our economy can basically function with much of the population sequestered indoors. This will lead to more work-from-home arrangements, as my colleague Will Oremus pointed out. It may also lead us to reappraise the necessity of working 40-hour weeks in offices — or even the necessity of all our jobs. The anthropologist David Graeber, the author of Bullshit Jobs: A Theory, notes that in the available research, over a full one-third of people say their own job is pointless. I’ve seen variations of that comment flit through my feeds and Zoom hangouts: Now that many are trapped indoors, sending out marketing emails or such while others are on the front lines of a health crisis, the “bullshit job” has suddenly been thrown into sharper relief.

“We have to reexamine the concept of production itself,” David Graeber said in a recent livestreamed interview about the future of work after the pandemic. He describes our current conception of production as based on “a male fantasy” of turning nothing into something, putting objects into the world. But that’s no longer imperative, or even realistic — we spend or should spend more time focusing on the care and maintenance of objects and systems as we do creating new ones. The health of the climate might depend on it; working and commuting less has been shown to lead to a significant decline in carbon emissions — like the decline that we’ve seen in the last month of the pandemic, and that would, of course, need to be expanded much further.

“The coronavirus shows us what we already knew, that when we are really forced to choose business as usual or each other, we will choose each other,” Eric Holthaus, the author of the forthcoming The Future Earth: A Radical Vision for What’s Possible in the Age of Warming, told OneZero. “That’s the same choice we’re being asked to make to address the climate emergency. This choice, on whether or not to continue with a fossil-fuel-powered economy, is clearer now than ever. The climate emergency demands that we work to actively replace these systems with more resilient ones, and the pandemic can be a catalyst to speed up that transition.”

We might realize, finally, that perhaps we don’t all need to spend 40 hours working per week, that health care should not be tied to employment, and that we don’t all need to be doing the work we’ve been doing — especially if we do not particularly enjoy it. We may realize that production ideals pegged to mid-20th century employment formations are no longer necessary — and that perhaps we can begin to untether ourselves from bullshit jobs, overwork, and reliance on outmoded systems.

What plague fiction can teach us about life in our post-pandemic future

“Since plague became some men’s duty, it revealed itself as what it really was; that is, the concern of all,” Albert Camus wrote in The Plague in 1947. If the history of pandemics and economic shocks can help us anticipate where the virus might lead our interlocking disease-battered societies, plague fiction might help us make sense of how we might manage as humans — what our individual obligation and sense of duty might be.

Take The Plague — the French existentialist’s now-even-more-famous book is speculative fiction about bubonic plague infecting a midsized city in the 20th century. It’s often read as an allegory for fascism, and maybe for that reason, it is, for my money, the single best work of fiction to read, or read again, with a pandemic raging outside our locked doors while we are governed by an administration with authoritarian impulses.

What should we expect when elites have been preaching free market libertarianism as gospel for decades, and have positioned shopping as an act of performative freedom?

Camus’ lesson is simple: In a plague, the only thing to do is whatever thing you can to preserve life. Stay indoors, perhaps, for starters. This cold, affirming calculus should be vital in the midst, the waning days, and those to come after the virus. We must do what we can, like Rieux, the indefatigable plague doctor, and refrain from malice toward those who do not.

“The evil that is in the world always comes of ignorance, and good intentions may do as much harm as malevolence, if they lack understanding,” Camus writes. “On the whole, men are more good than bad; that, however, isn’t the real point. But they are more or less ignorant, and it is this that we call vice or virtue; the most incorrigible vice being that of an ignorance that fancies it knows everything and therefore claims for itself the right to kill.”

It’s not hard to see echoes of the Reopen America cohort, egged on by Trump, and organized by his network, in these passages, and in the “many fledgling moralists… going about our town proclaiming there was nothing to be done about [the plague] and we should bow to the inevitable.” Meanwhile, Camus’ protagonists, who have formed “sanitary squads” to try to curb the spread of the plague, believe “that a fight must be put up, in this way or that, and there must be no bowing down. The essential thing was to save the greatest possible number of persons from dying and being doomed to unending separation.” We should note the limits to the text here — Camus too is wary of authoritarian cordons and draconian aftermaths of plague life as detailed in the nonfiction of Epidemics and Society.

As we adjust to a new normal in which we can expect waves of the coronavirus returning and the corollary waves of quarantine, we should take these words to heart — it can be tempting to disregard the right-wing protestors pushing for a reopening at the expense of people’s safety as rubes and assholes. Maybe — but what should we expect when elites have been preaching free-market libertarianism as gospel for decades, and have positioned shopping as an act of performative freedom? This is ignorance that “claims for itself the right to kill.”

So how do we counter this impulse? We have so many questions like this to answer. Pandemic fiction is a reliably popular and timeless genre in part because it engages them head-on. As Jill Lepore recently argued in the New Yorker, there are two main genres of pandemic fiction — plague diaries and apocalypse scenarios. One aims to make sense of lives prone to outbreak, and the other is a blunter instrument used to amplify a writer’s concerns about dangerous trends. (There’s also a sub-subgenre, speculative plague fiction, including zombie fiction — one of the most popular genres of the last two decades. More on that in a minute.) Many of those texts have proven not only prescient, but useful in contextualizing both the baffling and encouraging responses we’re seeing to Covid right now.

Since Mary Shelley largely originated the genre with The Last Man, these books have aimed to tell a blunt cautionary tale about one pernicious threat to the fabric of society or another — about the dangers of, in Shelley’s case, Enlightenment hubris. Or in Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, industrial capitalism. In Max Brooks’ World War Z, the zombies are a warning about pandemics themselves — the zombies proliferate like contagion. In books like Stephen King’s The Stand and Margaret Atwood’s Oryx and Crake, the unleashed virus is a bioweapon; the demise of the bulk of the world population can be traced to military hubris and toxic male ideology, respectively. These are useful reminders that though we rightly consider the concept of divine retribution via contagion absurd now, we are not entirely blameless — in placing profit before caution, for instance.

Zombie fiction like The Walking Dead allows us to imagine a world wiped clean of human failure. We solve our day-to-day problems by shooting our planets’ cohabitants through the skull. These Last Men-type stories, I’ve found, rarely have much useful to say about navigating a crisis, and much less how we got here or where we go next, besides oblivion. Many, in fact, perpetuate a detrimental myth of misanthropic savagery in hard times; people are more likely to come together, sociologists have shown, than to vie to become warlords.

Ling Ma’s 2018 novel Severance, on the other hand, which was much-discussed in the first weeks of the Covid crisis for its eerie prescience — definitely the buzzy plague read of those heady early pandemic days — does have much to say about how we got here. A satire of both the zombie genre, late capitalism, and millennial culture, Severance dissects the links between a world impossibly connected by supply chains, culture, and commerce and a disease that leaves us all mindlessly repeating our rote daily routines. The mysterious Shen Fever — so named because it originates in Shenzhen, China, a city known today as the “world’s factory” and as a manufacturer of everything from plastic trinkets to iPhones — spreads because we let it, because we don’t care to recognize or reorganize our patterns of behavior, because, perhaps, we are not able to.

In one of the book’s most gutting moments, the protagonist continues on at her pointless middle management job procuring cheap Chinese bookbinding contracts for specialty Bibles as the world collapses around her, all for the promise of a bonus that will be utterly meaningless by the time it reaches her bank account. It’s another reminder that this might be a good time for a lot of us to ask what we’re working for, and if it will be worth it when we come out the other side.

There is also room for optimism in plague fiction, as in Connie Willis’ 1992 novel The Doomsday Book. In 2051, years after (yet another) pandemic has decimated the world’s populations, medical science has found cures and vaccinations for most ailments — the young have never even experienced a cold. Meanwhile, national and international governing bodies have enacted a rigid and detailed set of codes and protocols to effectively contain and combat infectious diseases. So, when an apparently novel strain of influenza arises in Oxford, England, quarantine is administered, contact tracing is urgently carried out, and — not without protest — lockdown is effectively put into place. Protest groups gather to blame the outbreak on foreigners — the first known case was a man of Asian descent — and spit in the face of protocol. Many die, but, by and large, the disease is swiftly contained.

While the disease rages in the mid-21st century, a historian has mistakenly been sent back in time to the onset of the Black Death. She has been inoculated, so she vainly tries to help as the village where she’s been taken in is consumed by the plague. In the novel, it had been assumed by historians that people behaved selfishly, even vilely, when confronted by the disease — deserting their children, turning on each other, burning witches, and so on. Instead, citizens respect an ad hoc quarantine, lend aid to each other, and a priest gives his life tending the village sick.

It’s one of the book’s lessons, which I take to heart: We tend to underestimate the past and overestimate the future. We imagine that we’re inherently superior to past generations who struggled with disease—that our technologic solutions will inoculate us from pandemic — one reason why we failed to see this coming.

Plague fiction can emphasize both terror and parable — Poe’s famous “Masque of the Red Death” imagines nobility trying to cordon itself off from a plague, and throwing a lavish party for itself while the world succumbs to disease around it.

A handful of works seek to interrogate our relationship to the virus itself, like Ammonite, by Nicola Griffith. In Griffith’s award-winning novel, space colonizers are sent to a foreign planet, Jeep, where a virus decimates their population; all men are killed, and many women too. The remaining societies of women learn to coexist — to evolve — with the virus. Medical science and advanced technology can keep the virus at bay, but accepting that coexistence is a precondition for the long-term survival of robust societies.

I was so intrigued with Ammonite that I reached out to Griffith to get her thoughts on the role of speculative fiction in navigating real-world pandemic:

Optimistic stories like the Star Trek universe hold out promise for beneficial change after catastrophe: a cashless, egalitarian, cooperative, science-based civilization. Books like Andy Weir’s The Martian show us how working the problem could work as well in the near future as it did for Apollo 13. Books like Neal Stephenson’s Seveneves do the same for a planetary catastrophe — I’d bet that book has been read by many people in government disaster-advisory roles. But then we have two basic ideas balanced in opposition: Red-blooded rich straight white men will carve up the world between them and control resources, vs. a massive, international global scientific governmental response saves the human race. Which way will we go? It depends on who tells the better story.

Stories show us possibilities: what could happen if we are vile to each other; what could happen if we are progressive idealists; what could happen if we stick our heads in the sand and pretend nothing has changed. They are thought experiments — not just about crisis and technology but about human response to crisis and technology. And one of the reasons SF is so very useful for this is that it tries very hard to be both an optimistic and a rationally based genre. SF aims, still, for that sense of awe and joy, of the ineffable, of the ability of human beings to work together for the common good. And in these days of distrust and misinformation, we need reminding of utility, of goodness, effort, and common humanity: It doesn’t just feel better to be kind to each other, it’s vital for our survival.

Griffith echoes Camus’ assertion in The Plague that “there are more things to admire in men than to despise,” and the basic fact that it is nearly fundamental in our humanity to feel driven to work for the betterment of our communities, even at personal risk. Consumer culture has driven our connections with our communities and misplaced our priorities, as Severance illustrates. Yet now, almost everyone I know is donating goods or money or working on the front lines themselves or sewing personal protective equipment (PPE) because for-profit hospitals do not have enough of them. These people do not earn headlines the way that pro-business MAGA protesters yelling in the faces of health care workers do, though they vastly outnumber the latter.

They are simply doing what must be done — and what will have to be done again and again as this virus limps on throughout the year, and whenever the next virus emerges after it. We have not seen the last pandemic; as Camus notes, all this will have “to be done again in the never-ending fight against terror and its relentless onslaughts, despite their personal afflictions, by all who, while unable to be saints but refusing to bow down to pestilences, strive their utmost to be healers.”

Solidarity and community in the post-pandemic future

In the crisis days before the pandemic engulfed us, back when we only had climate change-enhanced wildfires, hurricanes, mass shootings, and the regular crises of capitalism to contend with, I found myself recommending one nonfiction book more and more frequently — A Paradise Built in Hell, by Rebecca Solnit. The thesis is perhaps not shocking, but it is quietly revolutionary in an era built around a pervasive ethos of self-sufficiency and greed-is-goodism. The book was largely a response to media narratives of “riots” and “looting” in post-Katrina New Orleans, but I find it relevant now more than ever.

“The image of the selfish, panicky, or regressively savage human being in times of disaster has little truth to it,” Solnit writes. “Decades of meticulous sociological research on behavior in disasters, from the bombings of World War II to floods, tornadoes, earthquakes, and storms across the continent and around the world, have demonstrated this.”

It’s imperative that we monitor our changes, heed the warnings of the past, and build transparent, accountable, and democratic structures to weather the chaos.

The zombie fiction, the Last Man scenario, the fear-mongering on CNN about misbehavior in times of pandemic — stories of selfish assholes hoarding toilet paper — are built on a false mythology.

“Am I my brother’s keeper?” Cain asks God — later in the same chapter that He condemned us to perpetual vulnerability to disease — and thus, Solnit writes, raises “one of the perennial social questions: Are we beholden to each other, must we take care of each other, or is it every man for himself?” Solnit answers in the affirmative, noting that after the 1906 San Francisco earthquake, intentional communities sprung up to care for the wounded and displaced. That the same happened in Katrina, to a much greater extent than the wanton looting — which was often carried out for survival purposes, regardless.

There is good news abound for the post-pandemic future; yes, we must fight cynicism, greed, and those eager for business above health. But most people will act in solidarity with the sick and the burdened, despite the headlines — history attests to it. We must find the networks to connect and sustain the overwhelming number of people searching to patch small improvements onto our tattered collective body.

If the stories of our past and future hold any wisdom, and I’m sure they do, the post-pandemic world will be wildly variegated: desperate and ameliorative, chaotic and promising, hopeful and oppressive. Income inequality may even out, surveillance powers will be invoked, public health systems will be revolutionized and fed with new data, work may decay or be renewed as corporate platforms seek to monopolize and seize power. New spaces may open, online and off; new equilibriums may be set. We must prepare.

Walter Scheidel told me that he anticipates “a contest between forces doubling down on the status quo — sustained support for finance and corporations and one-off emergency relief for workers and small businesses in order to ensure a return to business as usual, as after 2008 — and progressive forces pushing a more Bernie Sanders-like agenda into the mainstream. Outcomes will vary by country and depend on the severity of the crisis and existing configurations of power and institutions.” And of course: “In the end, much depends on how quickly science gets a handle on the virus.”

For now, it has invaded us, and we are responding. It’s all we can do. After all, as Nicola Griffith said, “Viruses are integral to the existence of the human organism; viruses are a major driving force in human evolution at the cellular level. Viruses make us who we are. And we are constantly changing.”

Like the authoritarians who desperately sprung up quarantine to combat the Black Death, and the innovators who seeded urbanism through science-based disease diagnosis, and the programmers training A.I. on a corpus of potential Covid treatments — we will run the gamut and experiment with policy and technology in the post-pandemic future. It’s imperative that we monitor our changes, heed the warnings of the past, and build transparent, accountable, and democratic structures to weather the chaos. That we push together when we see possibility. That we maintain solidarity for the afflicted and sympathy for even the ignorant.

We will outlast this plague. And another one will come. Like Camus’ doctor listening to the news reverberate that plague has been stricken from his city, we’ll have to temper our relief when relief comes, when we’re once again loosed into the bars and the festivals and the beaches, with the cycles of pandemic and human reaction in mind:

As he listened to the cries of joy rising from the town, Rieux remembered that such joy is always imperiled. He knew what those jubilant crowds did not know but could have learned from books: that the plague bacillus never dies or disappears for good; that it can lie dormant for years and years in furniture and linen-chests; that it bides its time in bedrooms, cellars, trunks, and bookshelves; and that perhaps the day would come when, for the bane and the enlightening of men, it would rouse up its rats again and send them forth to die in a happy city.