Television & radio

‘My mum said, “Why are the police arresting you? You must have done something”: the scandal behind TV's new Windrush drama

The BBC’s Sitting in Limbo tells howAnthony Bryan was sacked, arrested and threatened with deportation. The reporter who broke the story talks to his family and friends about their years of misery

by Amelia GentlemanA fantasy preview screening of the BBC’s powerful new drama Sitting in Limbo would have a handful of home secretaries lined up in the front row: Theresa May, Amber Rudd, Sajid Javid and Priti Patel – with David Cameron invited to sit alongside them. Further back, there would be places for the civil servants who devised immigration policy over the past decade, senior immigration enforcement officers and the governors of Britain’s immigration detention centres.

This memorable evening will, of course, never happen because of lockdown, and possibly also because this isn’t how the BBC organises its screenings. But I hope that these politicians and officials force themselves to watch the one-off drama at home when it airs in early June. They may find it uncomfortable viewing.

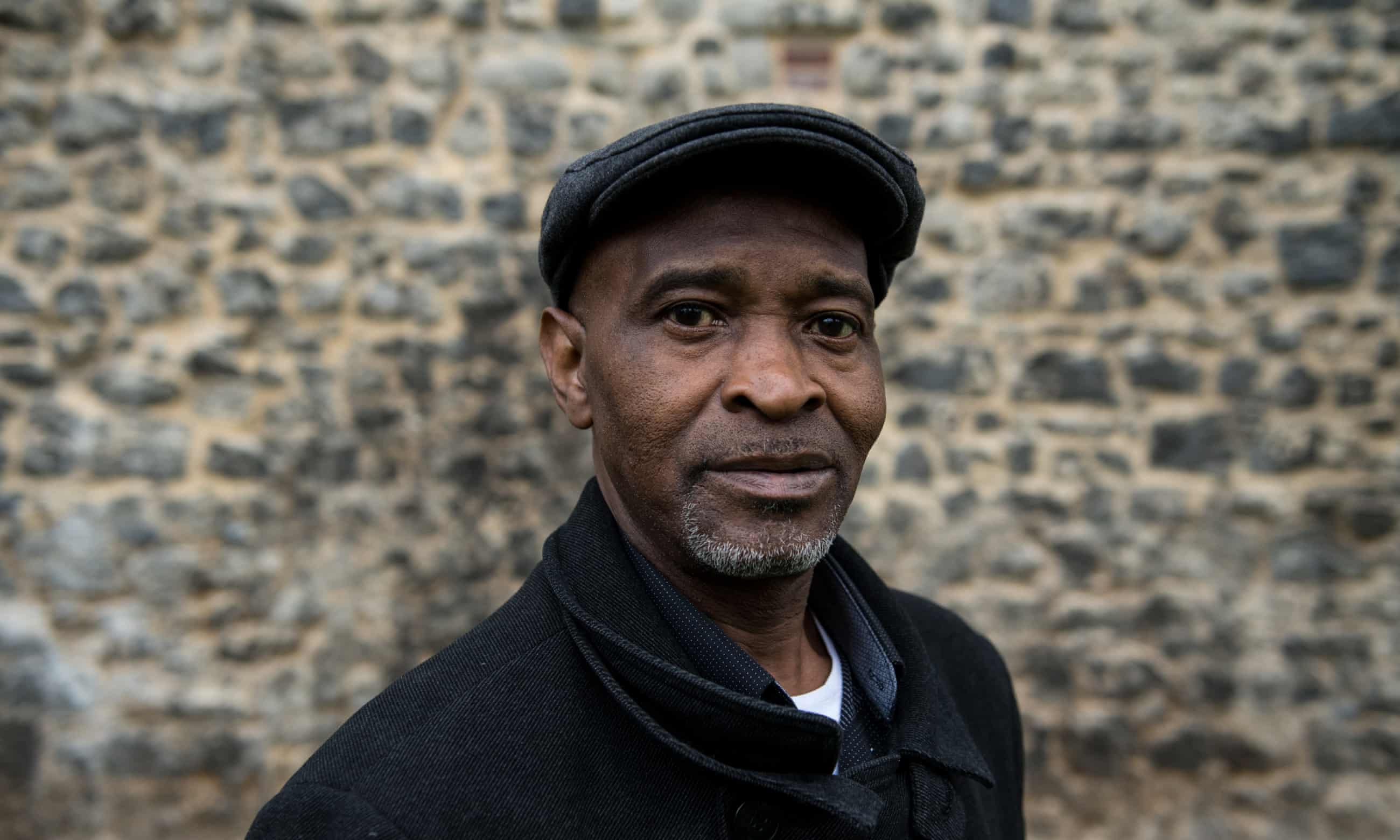

In 90 minutes, it tells the story of Anthony Bryan, 62, a builder who was mistakenly classified as an illegal immigrant by the Home Office in 2015, just as the government turned up the volume on its hostile environment policies, introduced to cut immigration numbers by making it very difficult for those without the correct documentation to continue living in Britain. Bryan was sacked from his job, twice arrested and twice sent to immigration removal centres, where he spent a total of five weeks, before being booked on a plane to Jamaica, a country he hasn’t visited since he moved (entirely legally) to London as an eight-year-old in 1965.

The drama, beautifully written by Bryan’s younger brother, the novelist Stephen Thompson, captures the catastrophic consequences of getting placed on the Home Office list of suspected illegal immigrants.

The casually sceptical language used by Home Office staff during their many interviews with Bryan is hard to listen to in the film. They repeatedly suggest he is lying when he sets out his life story. They refer to his children as his “alleged children”, and the headteacher who has dug up a photo of him at primary school in the 1960s as “the man you claim is your ex-headmaster”.

“I’m just doing my job,” one of the officials tells him. “It doesn’t matter that your job ruins people’s lives?” Bryan asks.

I watched the film with a rising fury, and was immensely upset by it, which is surprising because I’m already very familiar with the story. I met Bryan and his partner, Janet McKay, in December 2017, days after he had been released from his second stint in immigration detention, when he was still fighting a deportation order. His son had contacted the Guardian after reading about another long-term UK resident, Paulette Wilson, who had also arrived in the UK from Jamaica as a child in the 1960s and who had also been sent to immigration detention and was trying to fight off deportation to a country she hadn’t visited since she was 10.

During a long interview, Bryan mentioned that he knew several other people who were being similarly harassed by the Home Office: friends from childhood who had also been misclassified as illegal immigrants, had been sacked from their jobs and were struggling to prove a mistake had been made. Over the next few weeks, he and McKay put me in touch with Hubert Howard, Tyrone McGibbon and Jeffrey Miller, all of whom had moved to the UK legally from Jamaica in the 1960s. Interviews with them and dozens of others triggered a government apology, Rudd’s resignation and multiple promises to set things right.

Two years on, things have not been resolved. The last figures published show that only 36 people affected have received compensation (totalling £63,000 from a pot that officials expected to pay out between £200m and £500m). Bryan is still waiting.

The actor Patrick Robinson, who plays Bryan, says he was in tears as he read the script. “I knew this was happening to lots of people,” he says. “I wanted to be involved with the film in any shape or form.”

Robinson had a friend, Junior Green, who was refused re-entry into Britain after visiting Jamaica, despite having lived in the UK for 60 years, since arriving as a five-month-old. Green missed his mother’s funeral while he was stuck in Jamaica for five months, trying to persuade officials that he was British and should be allowed to travel home.

“I was aware of it before it hit the news. The whole West Indian community was just collateral damage in the debate on immigration. The government’s apologies are like putting a little piece of sticking plaster on a great big, gaping, festering wound,” he says.

His portrayal of Bryan’s shifting emotions, from bemusement to desperation to silently mounting rage, is extremely moving. Robinson says his performance was fuelled by his anger at a scandal that could easily have touched his own family. His parents came from Jamaica in the 1960s; his four older siblings were born in Jamaica, while he and two younger children were born in the UK, where his father tried to continue his career as an electrician, but later accepted work as a bus driver. “He kept getting laid off.” Was it racism? “Probably. He wouldn’t speak much about it. The history of people coming to the so-called motherland, and the history of double-standards that followed, is very close to me.”

Bryan is worried that most people have already forgotten the Windrush scandal, which is why he is so pleased that the film has been made. “People find it hard to believe that this happened. They can’t believe that I went through all that after 50 years here. People still trust the government; they just can’t believe they would do this to someone.”

He hopes the drama will imprint the scale of what went wrong in the minds of a new audience. He found revisiting the scenes in immigration detention especially painful. “It is so close to what I went through. I hope people will watch and understand the trauma,” he says. He wants to emphasise that his is just one story that illustrates what thousands have been through, and hopes that the film will push the issue back on to the political agenda. “I’d like immigration people to watch this to see what they put so many people through – people who shouldn’t be locked up in the first place.”

The film opens with a clip of Theresa May, when she was home secretary, standing behind a podium marked with the slogan “For Hardworking People”, announcing in an eminently reasonable tone: “The government will soon publish the immigration bill which will make it easier to get rid of people with no right to be here.” We see the then prime minister, David Cameron, remarking: “We would like to see net immigration in the tens of thousands rather than the hundreds of thousands.” And we hear him self-righteously declaring: “You put into Britain, you don’t just take out.”

Bryan and Thompson’s mother, Lucille, who put a lot into the UK during her time working as a cleaner in an east London hospital, appears on screen shortly afterwards. She struggles to understand why her son has been arrested. Bryan says: “My mum used to say: ‘Why are the police arresting you? You must have done something wrong.’” For a while, when everyone was questioning his story, he began to doubt his own memories.

“It made me angry again watching it,” McKay (who is played by Nadine Marshall) says. “I think it will make people get up in arms against the Home Office and the system when they see the injustice.”

Thompson recalls his horror when McKay called him in 2016 to tell him that his older brother had been arrested. “I thought there must have been a mistake; I couldn’t get my head around the idea of deportation. It had seemed to be a case of mistaken identity, and felt like a vague, nonserious threat – until Janet made it quite clear that he would be deported.” He watched what Bryan was going through, as the whole family rallied to try to get him out of detention.

He has reassessed his sense of how far Britain has moved on from the racism endured by his parents’ generation on arrival from the Caribbean. “The arguments our parents had in the 1950s and 1960s … I never thought we would be fighting them again; I thought we had won those arguments.”

Last year, he spent days talking to Bryan, nudging him out of a stoical refusal to dwell on his mistreatment. “He was very forthcoming on the facts, but he had to be cajoled into opening up personally. It’s not just about losing your job, can’t pay your bills, can’t claim benefits. There has been a real emotional cost, too, and as he has gone along, he has become more open about the effects of it.”

Thompson’s film shows Bryan enduring all the exhausting humiliations of a system that is designed to grind people into submission: the interminable queueing at Home Office reporting centres, where officials won’t listen to you, and – if they do – aren’t inclined to believe what you say; the hours wasted on hold to call centres in search of officials who might help; the financial difficulties that follow from being sacked, and told you aren’t eligible for benefits (despite having paid UK taxes for years); the embarrassment of having to rely on your children for food. It is a shattering portrait of a system that aims to wear its targets down until they begin to think the idea of self-deportation (back to a country they haven’t been to for half a century) is possibly the most sensible way out.

“He got a sense that, no matter what documentation he provided, it was not going to help,” Thompson says. He worries that the long delay in paying compensation is beginning to take its toll on Bryan. “My brother is naturally the forgiving and accepting type; he doesn’t do embittered. But the unfortunate reality is that the longer this goes on, and the longer the government drags its heels over the next stage, it will be hard for him to stay that way. There has been a slow, steady erosion of his desire to see the good in everything,” he says.

“He is trying to be patient, but the truth is that they are in very, very bad straits financially. He feels let down.”

I’ve been talking to McKay and Bryan periodically for two and a half years (and for a few startling seconds towards the end of the film, I’m figuratively on screen with them, played by Anna Madeley, somehow made to look disconcertingly like me). I’ve also witnessed a shift from optimism to disillusionment as the compensation process drags on.

Nothing here has been exaggerated. In some ways, the film’s strength lies in its subtlety. Many other Windrush victims had even more extreme experiences – exiled for years in unfamiliar countries, forced into destitution or made homeless.

And the Windrush issues explored here remain acutely relevant. It was the same hostile environment priorities that prompted the government in 2015 to introduce the NHS surcharge (which was partly withdrawn last week amid anger at the number of international healthcare staff forced to pay to access the NHS services they were working to provide and already paying taxes to fund). These policies also meant a Commonwealth veteran (who had served the British army for a decade in Afghanistan and Iraq) was this month charged £27,000 for an emergency operation to remove a brain tumour. Despite all the apologies, none of the legislation that underpins it has been repealed.

Ideally, the fantasy screening of this film would also see invitations sent to those affected. The BBC might need to book a larger venue to have room for the 12,000 people who have been granted documentation by the Windrush Taskforce over the past two years, proving that they are not (and never were) illegal immigrants. Invitations should go to people such as Trevor Johnson, who was forced to beg on the streets of south London to feed his children, after officials decided he was here illegally, and Joycelyn John, who was frightened by years of Home Office intimidation into accepting a “voluntary removal” back to Grenada, a country she had left aged four, 53 years earlier. At the end of the screening, there would be time for politicians to discuss the film with them. It would be a powerful way of making sure that lessons are finally learned.

Sitting in Limbo is on BBC One on Monday 8 June at 8.30pm, and then on iPlayer. Amelia Gentleman’s book The Windrush Betrayal has been shortlisted for the Orwell prize