Stocks Have a Psychologically Important Day

Passing key landmarks on the S&P 500 may have caused traders to reconsider why they have pushed the market so far.

by John AuthersTo get John Authers' newsletter delivered directly to your inbox, sign up here.

Dueling Narratives

One of the oldest standbys of the market reporter is the “psychologically important” landmark. It comes up frequently in market commentary, usually without explaining who finds it psychologically important, or why. It does, however, at least allow a lazy way to explain the frequent importance of intangible narratives, or of mental shortcuts, in market moves. Beyond that, it is often psychologically important to reporters to have at least some kind of an explanation for a strange move in the markets.

I bring this up because the S&P 500, the most important stock market index in the world in both psychological and many other terms, managed to breach three separate psychologically important landmarks in early trading Tuesday. It got back through the round number of 3,000; it managed to get above its 200-day moving average for the first time in the Covid crisis, suggesting it had returned to an upward trend; and it moved decisively above its 61.8% Fibonacci retracement level, having tracked it for several days. Here is the chart I tweeted early in the trading day:

Unfortunately, these barriers weren’t as psychologically important as thought. Either that, or they were so psychologically important to many traders that they felt unworthy to take the index there. The market tumbled sharply in the last hour of trading, leaving the S&P slightly below 3,000, which at this point is almost identical to the 200-day moving average:

What happened? Before we get into technical analysis, or looking at the charts, it is worth making clear that when valuations move a certain distance beyond rationality (when you would think they would be causing intense psychological pain to everyone trading the market) they cease to be useful for gauging the near-term future. This is particularly so when there has been a major external shock, as is the case at the moment. Judged as a multiple of this year’s earnings (as measured by the estimates collected by Bloomberg), the S&P 500 was already as expensive as it had been at any time since 2000. The P/E ratio briefly topped 24 in the early going. But few have a clue where earnings are heading, and in any case an expensive market can always get more expensive. So extreme valuations should tell long-term investors to beware, but don’t tell a trader to bail out instantly:

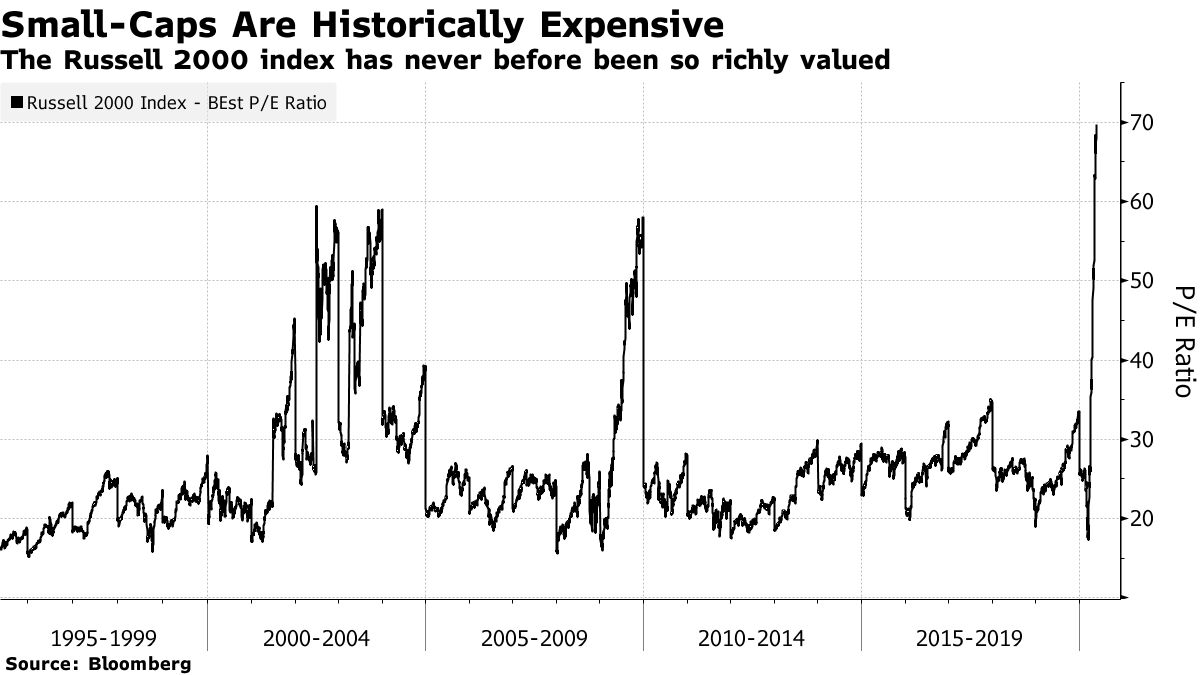

Incidentally, the large-cap stocks of the S&P 500 have been outperforming smaller companies for a while, but the overvaluation of the Russell 2000, the main U.S. index of small-caps, is even more extreme. On the same basis, the Russell is now valued at almost 70 times this year’s earnings, and is even more expensive than it was during the TMT bubble. This is nuts, unless a lot of traders are convinced that the brokers publishing forecasts don’t know what they are doing:

So with reference to their own history and fundamentals, U.S. stocks were hugely overvalued to start the day, and valuation provided no new reason to sell late in the day. To bulls who point to historically low bond yields, which weren’t around 20 years ago when stocks were last this expensive, we can add that the economy hadn’t just sustained a historic hit and unemployment wasn’t at record levels in 2000, either.

As I wrote recently, narratives can explain a lot. The narrative widely cited to justify the optimism at the day’s beginning was “back to work.” This was a national holiday weekend in the U.S. and the U.K., and it came with plenty of people socializing as normal and basking in the sun. There may be ugly arguments in both countries over the rights and wrongs of the lockdown and social distancing, but there is a growing sense that the virus has done its worst, at least for now. Why this narrative led to quite the ecstatic start to the market day is less clear — maybe it was psychologically important to see photos of people in the sun.

The narrative to explain why the market fell again in late afternoon surrounded a news story that the U.S. was considering sanctions against China over the situation in Hong Kong, with the president saying that something could happen by the end of the week. This is plainly market-negative, and a good reason to sell stocks. But as the entire long weekend had offered a series of reasons to treat the “New Cold War between the U.S. and China” narrative with deadly seriousness, and the markets had nevertheless zoomed off into bullish territory to start the day, it isn’t clear why this particular escalation should suddenly have an effect.

The “back to work” and “new cold war” are both reasonably accurate narratives that counteract each other. We still need an explanation for why traders took one of them seriously at the beginning of the day, and then felt persuaded by the other toward the end. That explanation might have something to do with the technicalities of how algorithms operate. Value has been doing terribly compared to growth for a long time. For some reason, plenty of people seemed to decide that Tuesday was the day to snap up bargains. Looking at the course of the day, value stocks surged at the start and never gave up their gains — growth stocks were more insipid and given away ground before news of the potential China sanctions. The “back to work” growth narrative might not have been so strong in the first place:

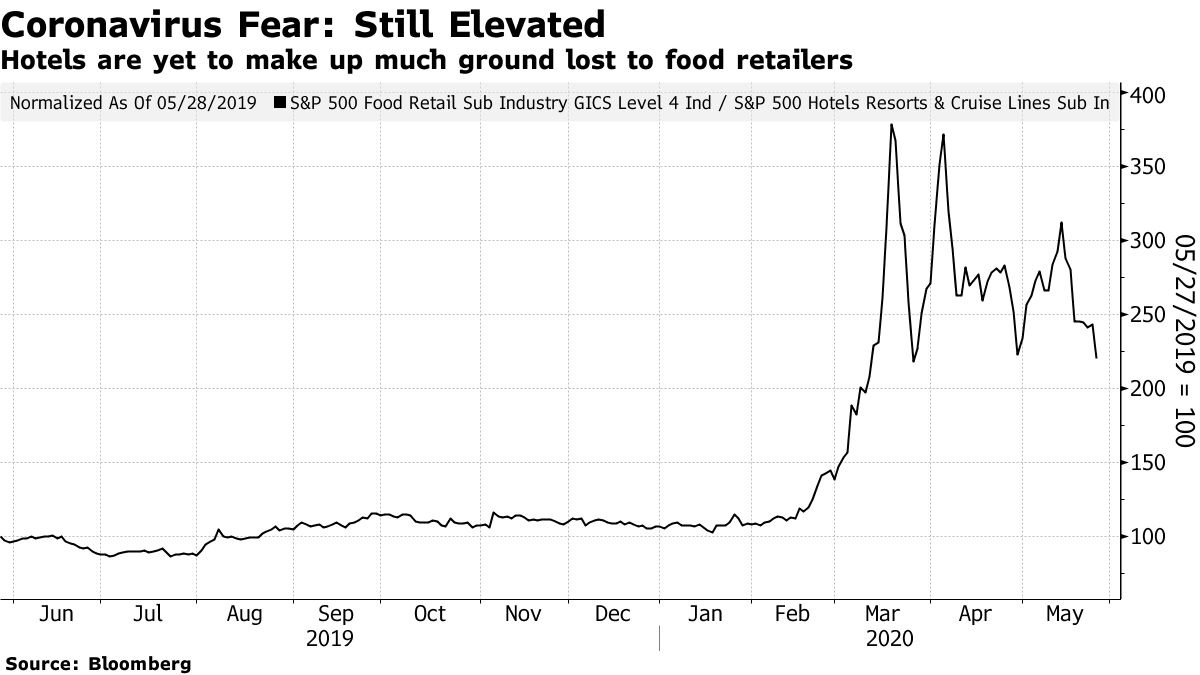

For another shred of evidence, I returned to the “coronavirus fear” measure that I started charting back in March, comparing the performance of two sectors directly affected by the lockdown; food retailers (which benefit) and hotels and cruise lines (which absolutely don’t). This shows that coronavirus fear is near its post-March low, but still hasn't broken out. On this simple measure, there wasn’t a big breakout in optimism about the chances of an early end to the lockdown Tuesday.

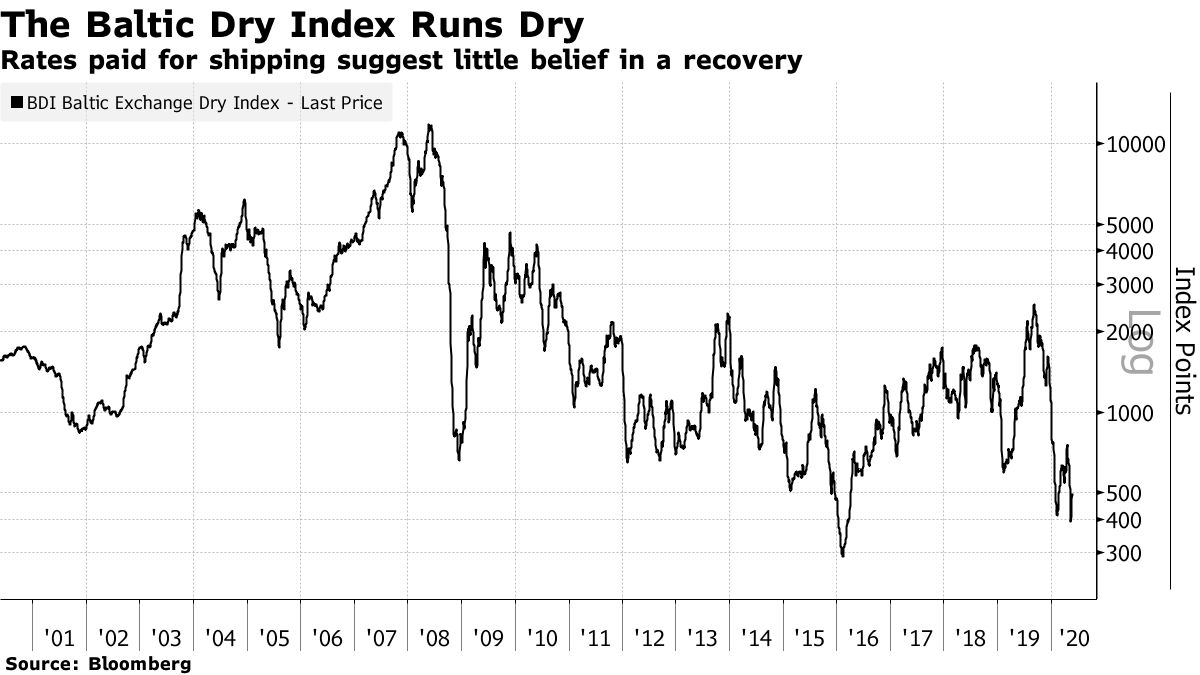

For another gauge of the growth narrative, we can follow the suggestion of Chris Watling, founder of Longview Economics in London, and look at whether there is support in other markets for the implicit narrative of a strong recovery in the making. Cutting a long story short, there isn’t. Look at the Baltic Dry index of shipping rates, a volatile but reliable long-term indicator of confidence in global trade. It avoided hitting its historic low from 2016, when the world was gripped by fear of a Chinese devaluation, but it gives no sign of an incipient recovery:

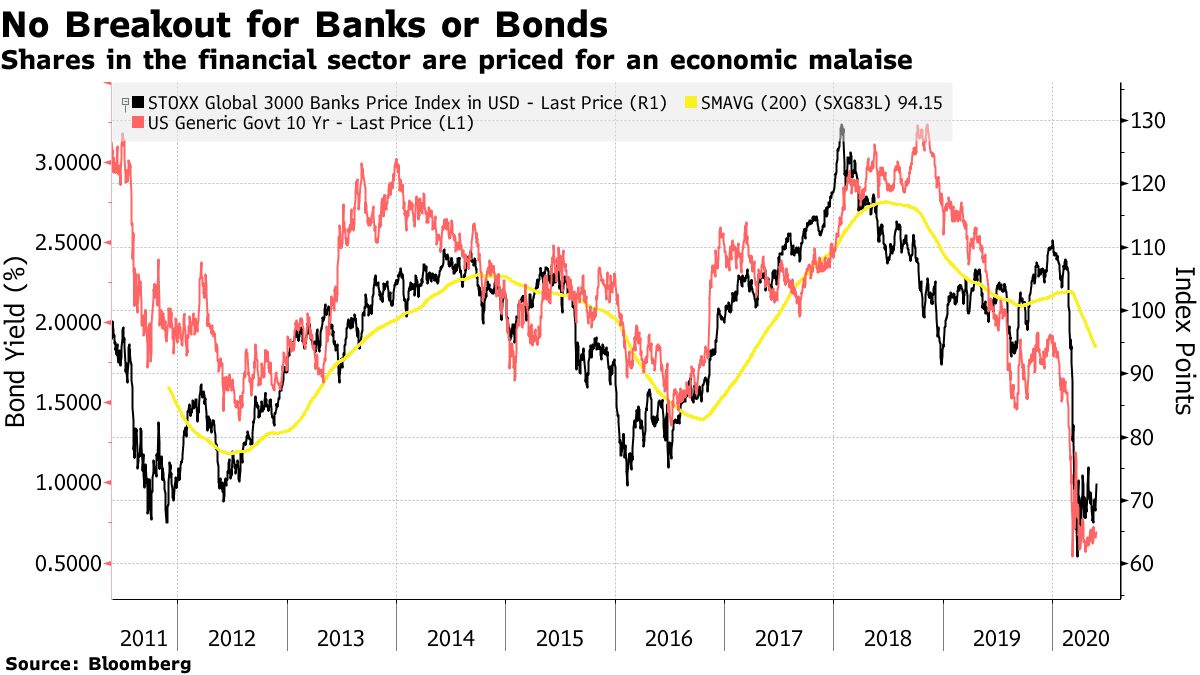

Much the same is true of industrial metals, also up a little from recent lows, but looking historically weak. If we move on to the more cyclical parts of the stock market that aren’t part of the “FANG” complex of dominant internet groups, we again find little confirmation for any great resurgence or cyclical rebound. Watling in particular draws attention to the Stoxx index of global banks, which has only just lifted off its lows for the decade. Bank investors are braced for some horrible second-order effects of the Covid crisis. Meanwhile, bond yields remain obdurately low and give no hint of a major reflation ahead:

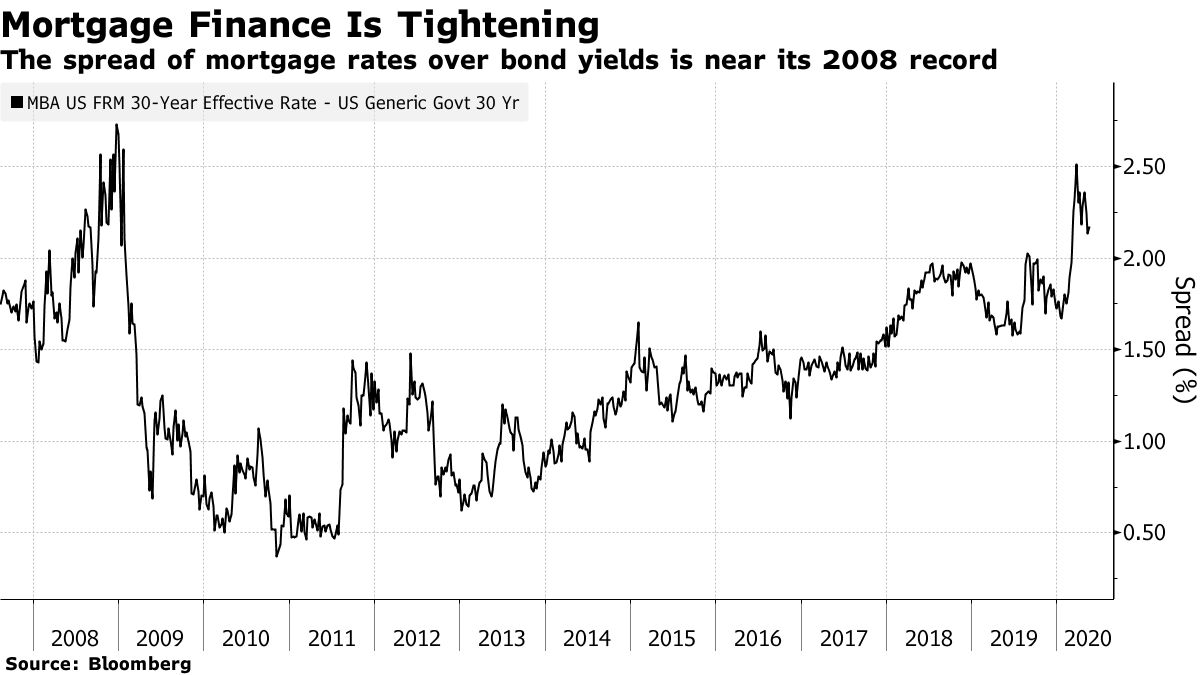

Looking within the entrails of the credit market, Watling notes that spreads of high-yield bonds remain elevated, suggesting continuing fear of defaults. (It is hard to reconcile this with historically high valuations for small-cap stocks.) Meanwhile, a perverse effect of the U.S. government’s move to protect people laid off due to Covid from having to make mortgage payments is that banks are proving more reluctant to lend. This is a natural result of being denied some income, but it means that spreads of 30-year mortgage rates over equivalent Treasury yields are almost at the all-time high set in the wake of the Lehman Brothers bankruptcy in 2008:

I think the case is made that financial markets aren’t expressing any general belief in a swift end to lockdowns followed by a swift economic recovery. Anyone who has bought stocks on that basis is likely to be disappointed. The next few months are likely to be dominated by the dueling narratives of the new cold war and the reopening after coronavirus.

But how do we explain the psychological breakthroughs of the day? We need to be cautious about technical analysis. Trends and patterns in markets offer a better guide to investor psychology than anything else in extreme times like this, but there are few hard and fast rules. The Fibonacci sequence, first discovered by a Medieval scientist observing the mating of rabbits, isn’t a clear determinant of market success. Neither is the moving average. But maybe, just maybe, passing landmarks like this can have a psychological impact. Maybe, just maybe, the breakout in the morning took the market to levels where investors were forced to re-examine exactly why they had taken things so far.

Survival Tips

Sport is beginning to make a tentative return to our lives, but many of us would be much happier if there were more of it, or at least enough to return daily life to some familiar rhythms. What has been good about the lockdown, however, is that it is prompting more and more of us to watch old sports events in their entirety. Many have famous endings and you forget the amount of excitement, and the number of moments that might have become classics of their own before the final denouement.

Let me offer two examples, both of which ended in extraordinary drama. In both cases, the famous final moment proves to have had plenty of excitement before it. First try Game 7 of baseball's World Series in 1960, which ended with a home run by Pittsburgh's Bill Mazeroski. It is still the only World Series game 7 to end with a walk-off home run, but there was much more to it than that. The see-saw drama goes on for two hours and it's extraordinary.

Then try the final game of England's football season in 1989, in which Arsenal beat Liverpool 2-0, thanks to a goal in added time, and thereby snatched the league title from them. Michael Thomas's strike was the most famous and dramatic in English football history until Sergio Aguero also decided a championship in added time, for Manchester City in 2012. But again, the whole game is extraordinary. You don't have to be a fan of any of the teams involved (I'm not) to find the drama intoxicating. And while everyone who knows anything about baseball, or about English football, knows how the games end, it's amazing how exciting they are to watch again. Until live sport returns, it helps us to survive.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

To contact the author of this story:

John Authers at jauthers@bloomberg.net