Can a Deadly Illness Have a Silver Lining?

Covid-19 warns us of other social changes, and reminds us we're animals, too.

by George Michelsen Foy

It's so easy to be overwhelmed by the news. The data smog that our society both creates and runs on has swarmed all over Covid-19, as it swarms over anything likely to generate clicks and advertising.

Such a massive volume of information is impossible for an individual to triage and comprehend effectively. One does not need to look further afield for people's inability, or unwillingness, to distinguish between factual evidence and false, contradictory or misleading statements made by those in power.

By the time one unit of information, true or false, has surfaced onscreen, another is muscling in to take its place. Who has time to fact-check at that speed?

In the long run, the worst virus we will have to suffer is, perhaps, the informational virus, the epidemic of limitless and uncurated data.

For what it's worth, I have found that occasionally thinking and researching outside the glut of data, without the endless reports of R-0 values and death rates, allows both some perspective, and relative calm.

None of this takes away from the tragedy of lives cut short, or from the grief of those who have lost loved ones, or from the fear endured by and for the vulnerable.

None of this should dilute our contempt for and rejection of those who lie, alter facts or manipulate policy for their own selfish ends.

Still: We should admire this virus. After all, we share a common ancestor: the first single-celled organisms from which life on Earth derived.

Eight to forty percent of the human genome is made up of virus genes. Covid-19 is our (very distant) cousin. Viruses, like us, are beautiful products of evolution: sequences of intricately folded DNA and RNA snugly wrapped in a coat of protein. Programmed to inject their genes into living cells, viruses build neatly engineered protein bridges to the protein coats of potential hosts. Once they have invaded the host cell, they cheerfully go about their business, which is replicating their own genes.

Viruses are everywhere. The human body contains 38 trillion of them. A single drop of seawater contains 10 million. The smartest viruses, like Covid-19, don't kill most of the animals they invade, but let the animals build their own social bridges to others of the same species, which allows the virus to cross over as well.

You can visualize social distancing as creating spaces a bit too wide for the bridge-engineers of the Corona Corporation.

Bridges of any kind bring movement, movement brings change. Pandemics are often both harbingers of, and the medium for, vast social change. The Black Death—not the product of a smart virus, but rather of a bacterium riding fleas and lice—to some extent brought about the Renaissance by wiping out such huge portions of Europe's population that it became necessary to think about labor-saving technologies and place more value on the workers who survived. The resultant rebound freed up time and funds to support thinkers and artists.

In Britain the same process allowed workers more money and leisure time to drink good beer, creating the British pub culture in the process.

During the Black Death, Europeans attacked the usual scapegoats—the Roma (gypsies), Jews, and 'foreigners'—for causing the plague, just as U.S. President Donald Trump is scapegoating Chinese now.

The 1918 flu—known as "Spanish" because Spain, as one of the few neutral countries in Europe, did not impose military censorship, which meant newspapers there were free to spread information about the disease locally, giving the illusion that the disease started in Spain—was possibly created by, and certainly spread by, the first global industrialized conflict.

The reason the 1918 flu was so lethal is probably because the stress and privations of wartime made the world's population uniquely vulnerable to a usually non-lethal virus.

Although it's near-impossible to pinpoint the 'patient zero' of the 1918 pandemic, two of the earliest traceable origins were a British Army field hospital in Étaples, France, and the U.S. Army's Camp Funston in Kansas.

The true Great War lasted from 1914 to 1946, with a troubled hiatus between the Treaty of Versailles and Hitler's invasion of Poland; the logistical and informational demands of the Great War's industrialized global conflict brought about the rise of the massive, transnational, corporate and governmental organizations that run our economies today. ("Transnational" here refers to the interlocking interests of nation-state bureaucracies.)

The Covid-19 pandemic is likely to speed up a process of organizational control already accelerated by the information revolution. Part of this process has consisted of turning the majority of the developed world's population into addicts—whether as consumers, Microserfs, or both--of informational technologies controlled by large organizations.

Consider this fact: The major portion of the average American's time—11 hours per day—is now spent absorbing data transmitted by screens.

A life centered on IT can only be made more so by Zoom, Facetime, and other videoconferencing methods used during the pandemic.

These are proving themselves to be efficient, if not emotionally or physically satisfying, replacements for in-person office

In my own job, the cost-saving aspects of teaching remotely must inevitably appeal to the bean-counters running big universities. Given such savings, it's doubtful that universities will ever fully return to face-to-face instruction.

These online methods generally are replacing the more human-intensive forms of activity whereby we spend time interacting, not only in task-oriented ways, but also in ways that enrich us personally, as living, breathing humans.

Artificial intelligence, as implied above, is likely to develop to the point where it approaches the science-fiction scenario of controlling or replacing vast swaths of human activity. The theoretical physicist Stephen Hawkings considered this next step in evolution to imply the extinction of humanity as we know it.

Such processes imply effective reduction of humans to mere brains nourished largely by screens and infotech: in sci-fi terms, the 'mind,' extended by IT, will increasingly replace the 'meat' of our animal selves.

Nevertheless, humans are still animals, physical beings from our toenails to the synapses of our prefrontal cortext. Our brains are not separate from our bodies: our minds need the senses, and vice versa.

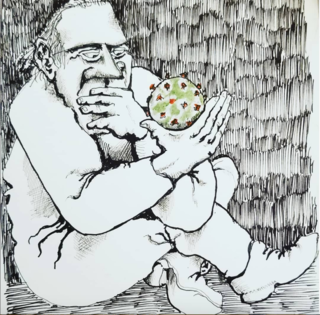

Consider this: If a baby rodent is raised entirely without touch it will die. If a human baby—who shares over 90 percent of its genes with rodents—is deprived of physical touch, s/he will also die or at least develop crippling dysfunctions.

The interesting and hopeful aspect of Covid confinement, of social distancing, has been an increasing acknowledgment of this need for touch.

"Skin hunger" is one term recently popularized to describe the need that people confined by this epidemic feel to physically see each other, and touch one another in the flesh.

The students I taught during the recent Covid term said they truly liked and looked forward to our Zoom class and appreciated being able to work in that context. Certainly we didn't work less or less well. Yet they also, every one of them, said they greatly missed and longed for the physical presence of their classmates.

More than 93 percent of our interpersonal communication occurs not through speech but through body language, most of which cannot be transmitted by Zoom or Facetime. It is hardly surprising that students should feel a reduction in the richness of teaching when so much information is eliminated.

This is not an argument, during the pandemic or even after it wanes, for seeing people in the flesh as we used to, nor for cutting short or watering down confinement practices necessary to restrict the Covid's spread.

But it is an argument for re-evaluating our importance, as human animals, to each other. It is an argument, not for ignoring or restricting infotech, but for balancing it better with the inter-human, physical contact we need to survive happily as whole beings.

All of us will die, if not from a virus then from other causes, and as we lie dying our thoughts and comfort will surely derive not from how many videogames we played, how many series we binged or teleconferences we participated in, but from the time we spent, fully and warmly and in-person, with those who were important to us.

As we emerge (carefully) from confinement: as we mourn those who did not survive the pandemic; one hopes we will also remember the salutary lessons our cousin Covid has taught us.