Street opera during lockdown

"They know all this. But they still say these things. I'm saying them now."

by Iain GalbraithThe murmur of men's voices. The curtain doesn't go up but parts. I'm looking down from ‘house right’, not exactly from the gods but, shall we say, from the second circle.

I recognize the men. They are standing in a circle in the middle of the street fifty yards away. I have exchanged nods with each of them and spoken to two on several occasions. And yet something about their appearance pierces me. Their faces are grey and serious, and perhaps because of my angle of view their circle seems compressed, despite their efforts to self-distance. The two I know are Romanian, but I hear them speaking German. The others, I must suppose, are not Romanian. I do know they all work on building sites. I've heard people say they work long hours for less than the minimum wage, pay no tax, no medical insurance, make too much noise, have no registered place of abode.

I know people who have said this. I also know that the same people know the men in the circle to be among the most vulnerable, in danger of deportation, uninsured work injury, denunciation, physical attack, and that they don't work cheaply for fun. They know all this. But they still say these things. I'm saying them now. All of us, including the men in the circle, are united in realizing something is terribly wrong. But whatever it is appears to belong to silence and the required order of things.

As in England (though not in Scotland) building work in Germany continues during lockdown. Impossible life and danger are the circle's subject.

In the past 20 years or so I have frequently seen circles of men in our street. Whenever there are road works involving a hole dug for access to a pipe, for example, you can bet that by about four o'clock in the afternoon, when people return from work, there will be several men solemnly gathered in a circle around its rim, staring down into the hole. Of course the holes are reminiscent of bomb craters: poignant reminders of injustice, social rupture, loss of life and deprivation. But what do the men talk about? Is it the metonymy of the palpable absence that draws them, its presence a sign of yet greater, as yet inexpressible absence? I once saw a woman join the circle around the hole. She later told me that she had been standing there "ironically". The men had quite simply been talking about different aspects of the hole and its purpose. The old normality.

Is today's circle any different?

In 'The Theatre and the Plague', contained in his series of short essays on the theatre Le théâtre et son double (1938), Antonin Artaud writes among other things of a plague that broke out in his native Marseille exactly 300 years ago this month. He recounts many other examples of plagues and their gruesome effects on populations from earliest times, but he calls the Marseille plague, apparently contained by quarantine, the only one on which we have modern clinical records. Nevertheless, the essay begins with the story of the Sardinian Viceroy Saint-Rémy who acts swiftly to protect the population by preventing a ship carrying the contagion from landing at the harbour of Cagliari. And yet the psychic energy that drove his action (at the time considered insane and despotic) came not from a knowledge of virology or hygiene, of which he had none, but from a nightmare in which he had witnessed the effects of pestilence.

But how can a dream, given the viceroy's lack of experience, be so percipient? And what of our unsettling circle? Artaud, comparing them with theatre, sees such phenomena as "emanations" of the "inner nature" of the plague. I translate:

The plague grasps images that are dormant, a latent disorder, and quickens them as extreme gestures; the theatre too takes gestures and forces them to extremes; like the plague it reforges links between what is there and what is not, between the virtuality of the possible and actually embodied nature. It rediscovers the notion of figures and archetypes that act like sudden silences, culminations, capillary arrests, fits of temper, inflammatory images thrust into our unexpectedly alert minds; it restores our dormant conflicts and all their force, giving them names we hail as symbols [...] These symbols, the sign of ripe powers held in bondage and rendered unusable in the real world, now burst forth in the guise of astonishing images that give existence and the freedom of the city to acts naturally inimical to social life.

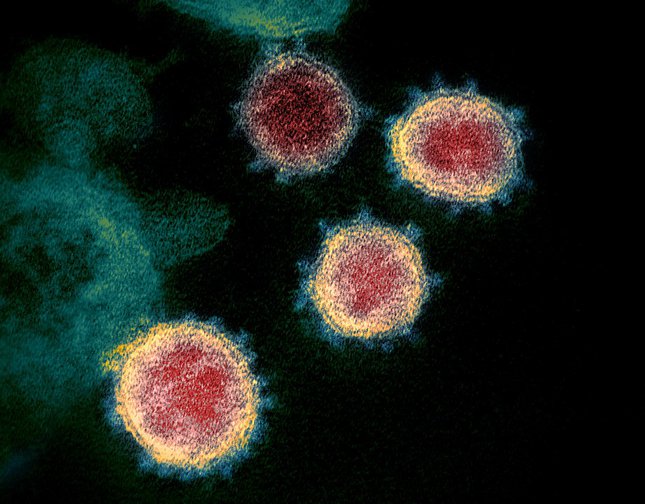

An exemplary latent image is newly embodied. The group of men, a small circle with its corona of heads, has meanwhile dispersed. The street is empty again but for a potent and distressing memory. The obscene image is broadcast globally.

This piece was originally published in the May edition of Splinters.

COVID-19 and the human side of globalisation

Usually, profits come before people. But this year, governments across the world have been forced to shut down their economies and put life first. Why?

Join openDemocracy for a live discussion on what the coronavirus tells us about globalisation, neoliberalism and our shared experience as humanity. Thursday 28 May, 5pm UK time/6pm CET

Speakers

Anthony Barnett Founder of openDemocracy, and author of ‘Out of the Belly of Hell: COVID-19 and the humanisation of globalisation’, which looks at how social movements since 1968 have reshaped the world.

Achille Mbembe Leading post-colonial philosopher who developed the idea of necropolitics: how politics can dictate who lives and who dies.

Thea Riofrancos Author of ‘A Planet to Win: Why We Need a Green New Deal’ and ‘Resource Radicals: From Petro-Nationalism to Post-Extractivism in Ecuador’. She is an Assistant Professor of Political Science at Providence College.

Chair: Réka Kinga Papp Hungarian journalist and editor-in-chief of Eurozine.