MAGIC IN THE MUNDANE

by Suktara GhoshA digital archive highlights the importance of documenting popular South Asian visual culture

We often don’t pay much attention to the significance of an image on a hoarding, poster or even a matchbox. Even though they form a major part of the world around us and influence us, our eyes mostly glaze over them, as we go about our daily business. It’s here that Tasveer Ghar, a free digital archive of South Asian popular visual culture, that documents, digitises and studies pop art, steps in.

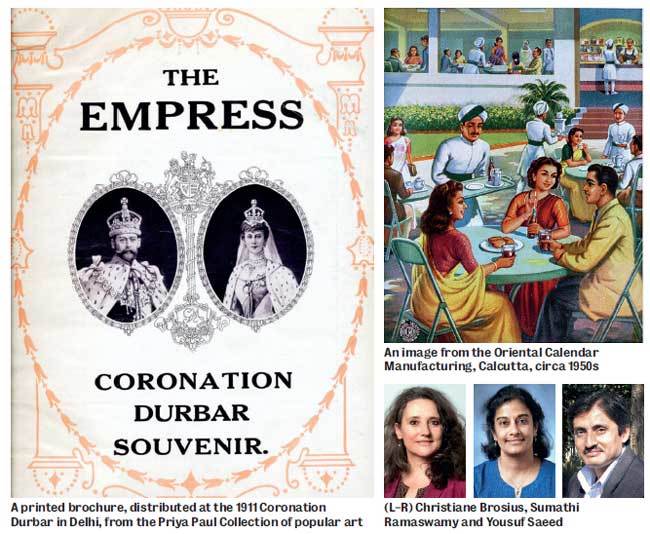

“By popular art, we mean art that has been mass printed and produced in the form of historical photographs, bazaar prints, film posters and hoardings, religious ephemera, political paraphernalia and commercial advertisements,” says Yousuf Saeed, a filmmaker and writer, who co-founded Tasveer Ghar, in 2006, with Christiane Brosius, professor, Visual and Media Anthropology, University of Heidelberg, Germany and Sumathi Ramaswamy, professor, History, Duke University, USA.

The trio, along with a contingent of scholars and collectors, has put together a formidable archive with around 7,000 pictures and 70 essays, which offers in-depth analysis of the history, practice and sociological impact of different kinds of pop art. Take their current theme ‘Manly Matters’, for instance. A pertinent topic, given the times, the project explores how the concept of masculinity has been culturally propagated through images in political cartoons, comic books, motorbikes in cinema, devotional art and advertisements in local pharmacies and alcohol shops, to name only a few. “Our initiative aims at not only documenting the immensely diverse visual cultures in South Asia, but also to think about how to write and think differently through images as more than mere illustration,” says Brosius, 54. According to her, visual popular culture is crucial in understanding social and political transformation and constructions of power and meaning — be it in ritual and everyday life or in political iconography.

Over the years, Tasveer Ghar has worked on varied themes such as popular visual cultures and practices in and around Muslim shrines, religious pluralism, and gender in the context of nation and everyday spaces. “Indians are amongst the most ‘iconophilic’ of peoples, ie, we love the world of images, which we surround ourselves with, and we play and experiment with it,” says Ramaswamy, 59. Although mass-produced images have been traditionally dismissed by the elite as irrelevant, kitschy and ‘not art’, for the people of Tasveer Ghar, the genre has for long been crying for attention. “It gives us an extraordinary lens into the world-making, aspirations and desires, and the love for colour and creativity among non-elite producers and consumers.”

For 55-year-old Saeed, the passion project has also been personally educative. “It taught me to read images like a historian, and even helps spot fake images,” he says, referring to a black-and-white photograph of Mahatma Gandhi and a small boy, captioned as the Dalai Lama, that he came across on social media recently. When he studied the picture closely, he felt something was amiss. “The brick wall behind Gandhi was common in the UK. I did some research and found that he’d gone to London in 1931, when this picture had been taken. The Dalai Lama was only born in 1935,” says Saeed. “The picture is clearly morphed.”

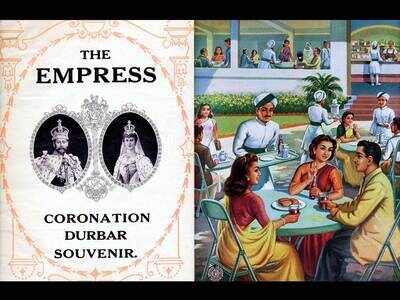

A major project for Tasveer Ghar has also been to document and digitise entrepreneur and art connoisseur Priya Paul’s personal collection of popular art. Apart from priceless original Raja Ravi Varma prints, old posters, calendars, postcards, commercial advertisements, textile labels and cinema posters, they also discovered a rare printed brochure distributed at the 1911 Coronation Durbar of the British Raj in Delhi, specifying dress codes for the invited rajas and nawabs of Indian states. While some of the images are displayed on the site, the complete 5,000-strong collection can be seen on Heidelberg University’s Heidicon Image Database.

► To access the archive, visit www. tasveerghar.net