How music therapy is helping some manage pandemic stress

by Jackie Vandinther CTVNews.ca Digital Content Editor ContactTORONTO -- Music therapy has long been known to help people cope with a wide array of health issues, from alleviating pain in patients with Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s disease, to reducing stress in children living with autism, to managing symptoms of depression or abuse. But now, many otherwise healthy people find themselves turning to music therapy as a way to manage the uncertainties and worries brought on by the coronavirus pandemic.

Yoni Collins was looking forward to finishing up his last year of film studies at York University in Toronto and was about to begin working on a big film project when the COVID-19 outbreak started spreading. Suddenly, the 25-year-old student, who lives at home with his family in Thornhill, Ont., was faced with uncertainty around his school’s graduation plans, and also didn’t know what would become of his job teaching guitar lessons with a Toronto-based company aptly named Stay At Home Music.

Collins was able to continue teaching guitar lessons online, but he noticed early in the lockdown that his music tastes had shifted. Instead of the country or rock he might have normally listened to, Collins said he started listening almost exclusively to jazz and scores, and even began dipping back into music he hadn’t listened to in 15 years. “I was listening to a lot of Hans Zimmer and Norah Jones,” Collins said in a phone interview with CTVNews.ca on Monday from his home in Thornhill. “It made me a lot more relaxed immediately.”

What Collins inadvertently began doing, listening to music with the intention to calm himself, is something more and more of us are trying to do, says Miya Adout, the founder and director of Miya Music Therapy, a Toronto-based company that offers certified music therapy in a variety of settings to clients of all ages and abilities. Adout says her music therapists work one-on-one with clients to get them closer to their therapeutic goals by using and listening to music in an active way in their everyday lives. “There’s a difference between music therapy and just listening to music as entertainment,” Adout told CTVNews.ca during a phone interview on Sunday. She believes the key difference is listening to music with intention

LISTENING TO MUSIC WITH INTENTION

The COVID-19 pandemic brought almost all of the services Adout’s company was providing privately and in long-term care facilities and education centres to a standstill, and forced to her to move the business online. The shift to providing music therapy virtually prompted Adout and a colleague to create ‘Music with Intention,’ a group program specially designed for adults looking to build their self-care toolbox through music therapy. Clients meet weekly with a certified music therapist through a Zoom session where they learn about the cognitive effects of music on the brain, the body’s physical responses to music, creating the right playlists, and journaling to track how certain songs make them feel.

Adout said the four-week program, which launched on May 18, is serving five people, and other clients are signed up for private music therapy sessions. She plans to start another program once this one is complete.

Collins said he found out about the program on Facebook, and was immediately drawn to it because he wanted to continue exploring and try to figure out why his music tastes had changed with the onset of the pandemic. “I listen to music a few hours a day. The idea that you could listen to music actively and not passively was something that intrigued me,” Collins added.

Whether it be jazz or any other genre of music, a study recently commissioned by the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra and carried out online by Mara Blue in April 2020 in the U.K. suggested that more adultsare turning to music intentionally to relieve stress brought on by the virus. In their survey, three in 10 respondents said they listened to orchestral music to help them relax while in lockdown. Another 18 per cent of people surveyed claimed orchestral music helped boost their mood when they felt worried.

IMMEDIATE RESULTS

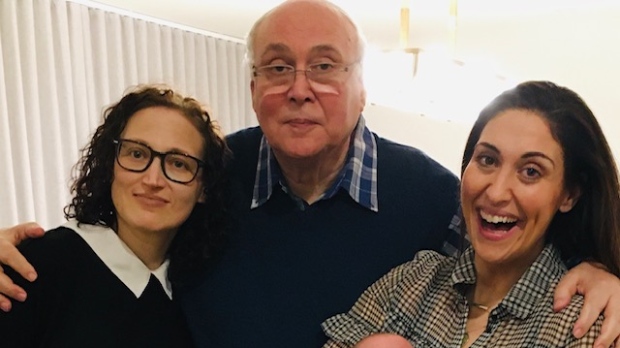

When Michelle Sonshine’s father, Barry Sonshine, was diagnosed with frontal lobe dementia two years ago, he was already experiencing symptoms of the disease. Sonshine said her father’s apathy and depression made it very difficult to engage with him. The 72-year-old, who lives at his home in North York, Ont., has essentially lost his ability to speak.

In an attempt to slow down the inevitable progression of the disease and try to engage her father, Sonshine introduced him to weekly sessions with a music therapist about a year ago. Sonshine said she noticed a positive impact almost immediately. “Music therapy has been incredible for my dad,” she told CTVNews.ca Sunday by phone from her home in Mississauga, Ont. “He’s basically non-verbal. The only time he uses words is through music therapy,” she said. “It’s one of the only times we hear him connect verbally and it’s one of the most remarkable things to watch.”

Now, Sonshine and her family have weekly family video calls in which they sing songs that Barry’s music therapist has given him. She said she’ll also play music during car rides with her father and engage him by prompting him to sing, follow the beat, or fill in the blanks to missing lyrics. Sonshine said what stunned her the most was that her father didn’t seem to have an interest in music at all before becoming ill. But she’s seen first-hand how music therapy is helping her dad calm down and feel more connected to his surroundings. And she said the results from sessions are felt long after they’re done. “His face is brighter. He looks at you more. He’s not as restless,” Sonshine said. “His physical therapy doesn’t light him up the same way as the music therapy does,” she added.

Before the harsh realities of the COVID-19 pandemic took hold, Kathleen Biggs’ 87-year-old mother, Betty Sulewski, was attending an adult day program at a facility specializing in dementia in Markham, Ont., that included music therapy sessions from Miya Music Therapy. Sulewski was diagnosed with severe dementia eight years ago, but Biggs said she’s seen her mother’s condition decline more rapidly in the last three, and even more so with the onset of the pandemic. Because of COVID-19, Sulewski’s outings to the day program ended, as did daily visits from her personal support worker. “She had no continuity in life,” Biggs told CTVNews.ca on Sunday in a phone interview from Minden, Ont. “I’m working from home. I do the best that I can, trying to keep her stimulated. But she was sleeping all the time,” she added.

About a month ago, Biggs began private, virtual music therapy sessions for her mother twice a week, and said she noticed some immediate changes in her mother’s mood through simple exercises that test her memory and keep her engaged. “They’ll sing Irish songs to her, put up pictures of Ireland, and ask her if she remembers things like the statue of Molly Malone,” Biggs said.

And Biggs said the impacts of each session last long after it ends. “She’ll just be more present. She might fall asleep if there’s nothing else going on,” Biggs said. “At least with this [music therapy], she’ll read the newspaper after, read a book. It ignites a bit of life in her,” Biggs added. Furthermore, the sessions have encouraged Sulewski to sing on her own, often piping up with an old Irish tune she used to sing to Biggs as a child. “It’s beautiful to hear my mother singing this Molly Malone song,” Biggs recalled through tears.

SELF-CARE TOOLS FOR THE PANDEMIC AND BEYOND

Certified music therapists employ a wide variety of methods to engage their patients, according to guidelines laid out by the Canadian Association of Music Therapists. Intervention techniques include, but are not limited to: singing, playing instruments, rhythmic-based activities to help facilitate mobility, improvisation, non-verbal expression, as well as composing and song-writing.

In the cases of Biggs’ mother and Sonshine’s father, both women admitted that the introduction of music therapy not only stopped the deterioration of their parents’ conditions, but also helped stimulate in them ways they couldn’t really find through any other means.

The list of benefits from music intervention and therapy is long and remains a widely researched topic of study by experts in the fields of music, psychology, cognitive behavioural sciences and neurochemistry, to name a few. And the applications for music therapy as a viable treatment for symptoms of depression, stress or anxiety in adults can extend far beyond the scope of a global health crisis, and be used by just about anyone at any given time. “When used with intention, music can alter your mood, change the way you feel,” said Adout. “We thought it was important to teach people those skills. Tools you can use at any time,” she said.

When asked if he’ll continue using music therapy after the pandemic subsides, Collins said he would “100 per cent” do so, and believes everyone can turn to music to boost their mood or find ways to incorporate it in their lives in a helpful way. “Every one can find serious benefits from it,” Collins said. “If I hadn’t found music therapy, I would not feel as calm as I do now, or as focused,” he said.