/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/66840516/castle_in_the_sky_villain_necklace_luputa.0.jpg)

Studio Ghibli’s first film, Castle in the Sky, is like no Hayao Miyazaki film that followed

Cookie banner

by Tasha RobinsonMay 25 to 30 is Studio Ghibli Week at Polygon. To celebrate the arrival of the Japanese animation house’s library on digital and streaming services, we’re surveying the studio’s history, impact, and biggest themes. Follow along via our Ghibli Week page.

The Studio Ghibli story began long before Castle in the Sky, the ambitious action-fantasy that was the Japanese animation house’s first release. Arguably, the story began when animators Hayao Miyazaki and Isao Takahata, two of Ghibli’s co-founders and its most prolific film directors, met and worked together on anime projects like the 1968 feature film Horus, Prince of the Sun and the 1970s Lupin the Third television series. Or fans could say it began before then, when Takahata and Miyazaki separately discovered their interest in animation, which led them to Japan’s Toei Animation, where they honed their talents and their narrative voices.

But given how significantly Miyazaki’s tastes and personalities in particular came to define Ghibli, it’s easiest to say that the studio’s story started with his immediate family. Miyazaki’s father Katsuji, an aeronautical engineer, was a key influence whose impact has been felt in every one of the animator’s major works. Miyazaki’s father ran a family business, Miyazaki Airplanes, and the director grew up around airline designs and parts. His obsession with the mechanics of flight stretches unmissably through all his films. But it’s particularly visible in Castle in the Sky, where half the action takes place aboard steampunk-ish airships, among fantastical flying devices, and ultimately in and around a flying city.

Miyazaki Airplanes manufactured parts for Japan’s Zero fighter planes during World War II, and that, too, had a long-term effect on the director’s thinking. The guilt he later expressed over his family’s part in the war is clearly expressed in his film Porco Rosso, a strange fairy tale about an Italian air ace navigating his homeland’s growing fascism. (And a curse that makes him look like an anthropomorphic pig, but that’s a separate issue.) Miyazaki’s feelings emerge even more clearly in his most recent feature film, 2013’s The Wind Rises, which turns a biography of World War II airplane designer Jiro Horikoshi into a meditation on flight, and the gap between engineers’ dreams and the military’s practical uses for them.

But in Castle in the Sky, Miyazaki’s feelings about the military, and his deep-seated love of flight, emerge in ways that wound up being unique in the core Ghibli catalogue. The film’s visual style is still recognizable in the studio’s films from 30 years later, and so are its character stylings and visual gags, but Castle in the Sky centers on something Ghibli has largely avoided ever since: an outright, uncompromising, unrelieved villain.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19998763/GHI_CastleInTheSky__Select3.jpg)

Castle in the Sky opens on a blimp-like airship where a young girl, Sheeta, is being held prisoner by a group of stern-faced military men led by the smirking Colonel Muska. When a group of sky-pirates, led by a bold, plump old lady named Dola, attacks the ship in an attempt to steal Sheeta’s crystal necklace, the girl escapes the cabin — but falls from the ship and plummets to earth, into the arms of a young miner boy named Pazu. As Dola’s gang, Colonel Muska, and the military all pursue Sheeta, the two children flee through a long series of action sequences that take them down into a series of underground mines, across a rickety series of elevated steam-train tracks, through a military fortress, and eventually to Laputa, the ancient, high-tech “castle in the sky.”

Sheeta’s necklace, it turns out, is a powerful artifact that holds the keys to Laputa. And while Colonel Muska pretends to represent the government, he wants access to Laputa entirely for his own sake. He’s a dapper, urbane sort of villain, capable of acting charming when it suits him, though most of his gentler words include veiled threats. He proves more than capable of threatening Pazu and Sheeta’s lives, and attempting to kill them. When he does get his hands on Laputa’s power, he casually uses it for murder on a mass scale that’s shocking in what’s mostly an amiable children’s adventure. He’s clearly a megalomaniac, a ruthlessly amoral power-seeker who doesn’t care about other people’s lives. Given access to an overwhelmingly powerful weapon, he immediately sets out to grind the world under his heel. And as villains tend to in children’s stories, he pays the price for his hubris.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19998765/Muska.jpg)

But none of that is typical for Ghibli movies. Castle in the Sky also explores a completely different kind of villain, one that wound up becoming much more of a model for Ghibli’s films — and Miyazaki’s in particular.

When the pirate queen Dola is first introduced (she’s known as Dora in some translations, as Castle in the Sky has been released in English multiple times, with varying names and dialogue), she appears to be as much of a villain as Muska. Her pirate crew — eight comically clumsy Large Adult Sons, and a mechanic who may be Dola’s husband and the crew’s father — ruthlessly pursue Sheeta because they’re looking for Laputa’s supposed treasure. In the process, they casually destroy anything that gets in their way. When Muska disappears with Sheeta, Dola takes Pazu captive and her boys wreck his home.

But over the course of the film, Pazu and Sheeta impress Dola, and her softer side rapidly emerges. When Pazu begs to come with her and her sky-pirates to get Sheeta back from the military, Dola accepts because she thinks he’ll be useful in manipulating and controlling the girl. Once Sheeta’s on board the pirate ship, Dola’s sons similarly melt, from rough-and-tumble fighters to sheepish, easily cowed kitchen assistants. (The 2003 Disney script translation, which implies they all want to marry Sheeta even though she’s a prepubescent girl, is a deeply weird touch, and it isn’t reflected in other versions.) By the end of the film, the pirate band and the two children are all clearly invested in each other’s survival and happiness, and they part ways as friends.

The Dola gang’s brief position as bad guys is Ghibli villainy as later fans would see it, more as a matter of perspective and unfamiliarity than actual evil. Only two of Hayao Miyazaki’s later movies actually have traditional villains: the Witch of the Waste in Howl’s Moving Castle, and the monstrous witch Yubaba and her immediate coterie in Spirited Away. Like Dola, both of them similarly soften as their films go on.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19998760/Dola.jpg)

Yubaba never exactly becomes an ally to Spirited Away protagonist Chihiro, but she transforms from a terrifying unknown into a gentler opposition. She isn’t destroyed or even defeated, Chihiro just learns not to be frightened of her. Other temporary villains in Spirited Away — a frightening white dragon, the terrifying monster-baby Boh, the people-eating creature No Face, Yubaba’s harpy familiar — all transform into kinder, smaller versions of themselves, and seem happy with the transition. The Witch of the Waste, meanwhile, seems much less cheery about the magic that breaks her down into a gentle old woman. But she, too, is rendered harmless and approachable, so early in the film that she barely has time to pose any real threat.

And while from some perspectives, the fierce human leader Lady Eboshi in Princess Mononoke or the controlling wizard-scientist Fujimoto in Ponyo might seem to fill the villain slot, they’re also both relatable from an outside perspective. Eboshi is a pragmatist, trying to rescue her people and give them somewhere to live. While her choices are destructive and ruthless, they’re also selfless and heroic. Fujimoto is just a concerned father who’s holding his daughter back for the same reason any parent might — to protect her from the threats of the world.

In other Ghibli movies, the danger threatening the protagonists comes from within, not without. When Satsuki and Mei almost give into despair over their mother’s illness in My Neighbor Totoro, and Mei wanders off alone, they’re threatened more by loss of hope than by any evil. Kiki in Kiki’s Delivery Service and Kaguya in The Tale of the Princess Kaguya find depression much more dangerous than any adversary. And many other Ghibli movies, like When Marnie Was There, From Up On Poppy Hill, Whisper Of The Heart, and Only Yesterday, spend more time contending with mild melancholy than with fear or fighting. Even the criminal manipulator Renaldo Moon in The Cat Returns is more trickster friend than determined foe.

Why did Ghibli — and Miyazaki in particular — so determinedly detach from conventional protagonist/antagonist stories? That question seems to particularly plague American journalists, who periodically ask him the question, on the rare occasions when he permits interviews. Miyazaki tends to gently dodge the issue, but when former Pixar honcho John Lasseter asked him about it in 2009 as part of an Academy Awards retrospective, Miyazaki offered one explanation: he just has too much empathy.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19998768/GHI_CastleInTheSky__Select1.jpg)

“When I create a villain, I start liking the villain, and the villain becomes a being who is not really evil,” he tells Lasseter. As an example, he brings up one of the old 1940s Fleischer brothers Superman cartoons, where an antagonist has created a secret underground lair. The level of effort and focus involved in a scheme like that, Miyazaki says, should be admirable in its own way — even lovable. “Villains actually work harder than the heroes,” he says.

He also suggests that given Ghibli’s long production process, spending years embedded in outright irredeemable characters is emotionally wearying. “Making an evil creature that really has an empty place or a hole in his heart is very tragic and depressing and sad to draw,” he says in that same interview. “So I don’t like drawing them. You can see animators drawing, and when they draw a happy face, they are smiling as well. When they draw a bad character, they’re grimacing and looking fierce. So I think it’s better to have a smiling face more than a grimacing face.”

That response may seem a little facile, given that some Ghibli films do go to such grim and horrifying places, exploring disease or suffering or death. Those threats just rarely have a single evil face to represent them. They aren’t outsized baddies, they’re just negative emotions, like Kiki’s depression, Howl’s body-melting sulk-fit, or Chihiro’s fear of change and the unknown.

Or they’re functionaries and societal forces that are too big to grasp or fight. Madame Suliman in Howl’s Moving Castle represents a cruel and implacable military, and the way she puts a kindly face on it is as evil as anything Muska does — but she isn’t at the center of the story. The tanuki in Pom Poko are fighting human urbanization and the disappearance of the wild. Seita and Setsuko in Takahata’s heartbreaking Grave of the Fireflies are suffering in wartime, but neither the aunt who resents their upkeep nor the soldiers who bomb their town are presented as traditional villains. Curtis in Porco Rosso is the face of the American military, and the hero’s primary rival. But he’s also a comic figure that has nothing to do with the story’s real threats — the rising tide of Italian fascism, and the slowly changing post-war world.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19998769/GHI_CastleInTheSky__Select2.jpg)

Ghibli’s only other traditional villain is Cob in Tales From Earthsea, a selfish, predatory wizard who the heroes have to face and defeat. He feels like an anomaly in Ghibli’s library, an artifact of the source material — Ursula K. Le Guin’s fantasy novels, which follow a more traditional hero’s-journey arc than Ghibli’s movies generally do. He’s also Ghibli’s least memorable villain, less relatable than the abstract threats of depression and fear, and less intimidating than the unstoppable forces of industrialization and the military. Compared to the threats in the Ghibli movies that have them, he seems petty and predictable.

Ghibli’s stronger movies often push their threats to the background, but at the same time, they present humanity’s urge for conquest and the indifference to human suffering as inevitable and unchangeable, even unreachable. And that backdrop of sorrow and inevitability speaks to the heart of Ghibli’s longtime philosophy. What makes heroes in Ghibli worlds is the determination to soldier on, to be brave in the face of fear or sadness or hardship. Courage doesn’t always let the protagonists win, or even survive. It doesn’t always let them change the world.

But in Castle in the Sky, it does. Ghibli’s first movie treats villainy different than its followers. But in other ways, it lays out a pattern that the studio’s later movies would follow closely, particularly in Dola’s secret gentleness, the military’s greed and inefficiency, the hilarious clumsiness of crowds and mobs, and the breathtaking feeling of flight.

And more than that, Castle in the Sky sets a course for Ghibli in the ferocity Pazu exhibits as he tries, over and over, to reach Sheeta’s side against long odds and implacable forces. (He’s up against gravity and entropy more often than he’s up against Muska.) Ashitaka’s determination to help San in Princess Mononoke, Seita’s battle for Setsuko’s life in Grave of the Fireflies, Ponyo’s obsession with Sōsuke in Ponyo, Chihiro’s bravery on Haku’s behalf in Spirited Away — they all start with Castle in the Sky, and its central relationship. Where villainy isn’t core to Ghibli movies, determination, loyalty, and love are.

And that’s because Ghibli movies focus on how personal connections make life worthwhile, far more often than they focus on battles to be won or worlds to be conquered. Ghibli characters can’t always change the larger world, or end suffering, or solve the problems of human greed and stupidity. But in Castle in the Sky and the films that followed, they can face whatever forces are arrayed against them, and make a difference for the people they love. That’s a message that resonates for real-world viewers, far more than the promise that cackling villains will be defeated, and it’s one of the secrets that’s made Ghibli so memorable over the past 35 years.

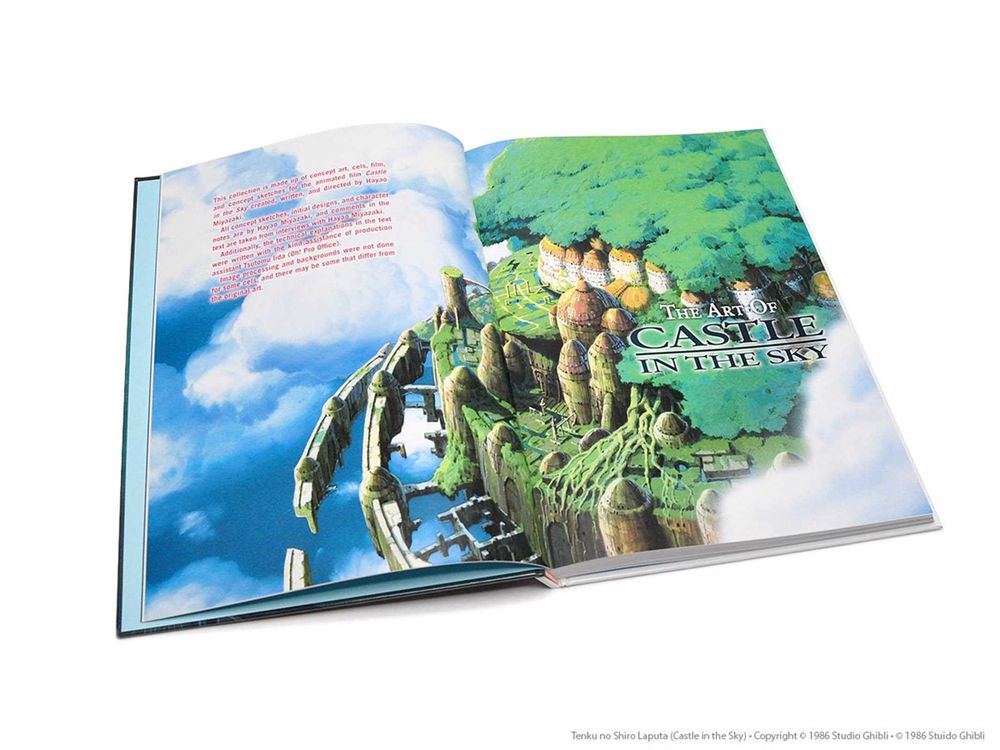

The Art of Castle in the Sky

The 194-page art book dives deep into the animation and storytelling of Studio Ghibli’s first film

link copy 2Created with Sketch.

Viz Media

Amazon / $21.49 Buy

Vox Media has affiliate partnerships. These do not influence editorial content, though Vox Media may earn commissions for products purchased via affiliate links. For more information, see our ethics policy.